Share

26th March 2018

11:53am BST

Sport is an extension of our culture and an extension of our society and those that play sport often play the sports that are the most popular in their local area.

In Ireland, the three most popular team sports are rugby, football and gaelic games but there's an attitude among people from a certain generation that you must belong to one or the other.

Remember the comments from Laois GAA county board member Kieran Leavy last year?

For those of you that are unfamiliar with Leavy's work, here's one of his highlights:

“If a young lad comes and says he is going to play soccer, he needs to be told ‘alright, go but we don’t want you anymore’.

“I know that sounds terrible but it is my opinion. We are going to have to draw our battleground because there is a war coming."

Leavy is going into the trenches and there will be other idiots that will be standing right there with him waiting to fight a fight with no real winner, but if he took a second to step back from this code war he's convinced has taken a hold of the country, he'd realise that there are examples of multi-sport athletes at the highest level in each sport.

Lee Keegan played both rugby and gaelic football. Anthony Tohill played reserve games for Manchester United and won an All-Ireland final with Derry. Kevin Moran played for United and Dublin. Kevin Nolan, the man of the match in the 2011 All-Ireland final Kevin Nolan, was on the brink of signing for Leicester City as a 17-year-old.

Simon Zebo was an excellent hurler. Tadhg Furlong, Sean O'Brien, Robbie Henshaw, Tommy Bowe and Rob Kearney all had some grounding in gaelic football. Darren Sweetnam played intercounty hurling for Cork and now plays on the wing for Munster.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/974921369036181504

Shane Long played hurling at minor level for Tipperary. Seamus Coleman could have played for Donegal according to former manager Rory Gallagher if he had have stayed with gaelic football instead of soccer.

The list goes on and on and on.

Ireland is littered with examples of multi-sport athletes that certainly benefited from playing a number of different sports during their development, and while that list will only continue to grow, you have the likes of Leavy and Irish Independent columnist Neil Francis sprouting nonsense about how there is a code war upon us or how the Irish people are embracing rugby as their new national sport.

Francis walked by me in the press box at the Ireland v Scotland match earlier this month with a Ralph Lauren puffer jacket on, I wonder who the people he's referring to as the people of Ireland?

As Mary Hannigan highlighted in her excellent Irish Times column earlier this month - 'Kiely’s in Donnybrook does not reflect the wider Irish society'.

Of course, the great hope for Irish Rugby is that it continues to shatter stigmas and stereotypes as the likes of Sean O'Brien, Tadhg Furlong and Ulster's Joe Dunleavy, an excellent Donegal GAA prospect now playing for the Ireland U20s, continue to rise to through the ranks.

Irish Rugby may benefit massively over the course of the next few decades if they can fulfill their potential and win a Rugby World Cup, or multiple Grand Slams and Six Nations titles, all of which are entirely possible under Joe Schmidt, but the idea that one sport has to be the national sport is ludicrous.

Kerry will always be a gaelic football heartland. Hurling will always be the dominant sport in Kilkenny. Soccer is huge on the north side of Dublin while rugby enjoys a similar influence through the city's south.

But ultimately, who cares? Who honestly cares?

There are so many examples of players that play different sports, why do we need to be told twice in one month on two different national platforms that one particular sport has now become the national sport, when we know by looking at playing numbers alone that rugby is a distant third behind both Gaelic codes and football.

Maybe that starts to change if Ireland go on an unprecedented run of success under Joe Schmidt but this idea that you can gauge the popularity of an Irish sport by looking at viewing figures is tainted at best.

Sport is an extension of our culture and an extension of our society and those that play sport often play the sports that are the most popular in their local area.

In Ireland, the three most popular team sports are rugby, football and gaelic games but there's an attitude among people from a certain generation that you must belong to one or the other.

Remember the comments from Laois GAA county board member Kieran Leavy last year?

For those of you that are unfamiliar with Leavy's work, here's one of his highlights:

“If a young lad comes and says he is going to play soccer, he needs to be told ‘alright, go but we don’t want you anymore’.

“I know that sounds terrible but it is my opinion. We are going to have to draw our battleground because there is a war coming."

Leavy is going into the trenches and there will be other idiots that will be standing right there with him waiting to fight a fight with no real winner, but if he took a second to step back from this code war he's convinced has taken a hold of the country, he'd realise that there are examples of multi-sport athletes at the highest level in each sport.

Lee Keegan played both rugby and gaelic football. Anthony Tohill played reserve games for Manchester United and won an All-Ireland final with Derry. Kevin Moran played for United and Dublin. Kevin Nolan, the man of the match in the 2011 All-Ireland final Kevin Nolan, was on the brink of signing for Leicester City as a 17-year-old.

Simon Zebo was an excellent hurler. Tadhg Furlong, Sean O'Brien, Robbie Henshaw, Tommy Bowe and Rob Kearney all had some grounding in gaelic football. Darren Sweetnam played intercounty hurling for Cork and now plays on the wing for Munster.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/974921369036181504

Shane Long played hurling at minor level for Tipperary. Seamus Coleman could have played for Donegal according to former manager Rory Gallagher if he had have stayed with gaelic football instead of soccer.

The list goes on and on and on.

Ireland is littered with examples of multi-sport athletes that certainly benefited from playing a number of different sports during their development, and while that list will only continue to grow, you have the likes of Leavy and Irish Independent columnist Neil Francis sprouting nonsense about how there is a code war upon us or how the Irish people are embracing rugby as their new national sport.

Francis walked by me in the press box at the Ireland v Scotland match earlier this month with a Ralph Lauren puffer jacket on, I wonder who the people he's referring to as the people of Ireland?

As Mary Hannigan highlighted in her excellent Irish Times column earlier this month - 'Kiely’s in Donnybrook does not reflect the wider Irish society'.

Of course, the great hope for Irish Rugby is that it continues to shatter stigmas and stereotypes as the likes of Sean O'Brien, Tadhg Furlong and Ulster's Joe Dunleavy, an excellent Donegal GAA prospect now playing for the Ireland U20s, continue to rise to through the ranks.

Irish Rugby may benefit massively over the course of the next few decades if they can fulfill their potential and win a Rugby World Cup, or multiple Grand Slams and Six Nations titles, all of which are entirely possible under Joe Schmidt, but the idea that one sport has to be the national sport is ludicrous.

Kerry will always be a gaelic football heartland. Hurling will always be the dominant sport in Kilkenny. Soccer is huge on the north side of Dublin while rugby enjoys a similar influence through the city's south.

But ultimately, who cares? Who honestly cares?

There are so many examples of players that play different sports, why do we need to be told twice in one month on two different national platforms that one particular sport has now become the national sport, when we know by looking at playing numbers alone that rugby is a distant third behind both Gaelic codes and football.

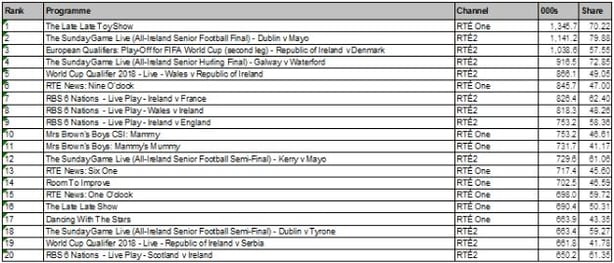

Maybe that starts to change if Ireland go on an unprecedented run of success under Joe Schmidt but this idea that you can gauge the popularity of an Irish sport by looking at viewing figures is tainted at best.

Ireland's Grand Slam win over England on St. Patrick's Day, a TV3 executive's dream scenario, commanded a television audience in excess of 1.3 million but we also know that 1.41 million people watched last year's All-Ireland final between Dublin and Mayo on RTE, and that 1.04 million people watched the second leg of Ireland's World Cup play-off with Denmark.

Are we really going to proclaim rugby as the national sport because roughly about 159,000 more people watched Ireland's third ever Grand Slam - against England - on St. Patrick's Day - than they did an All-Ireland final?

There are GAA county board members that have likened kids playing different sports to preparing for war, and former Irish rugby internationals basing rugby's rise as Ireland's new national sport off of television ratings of one match and his conversations in a restaurant with a Polish waitress.

The conversations about which sport is the nation's sport are usually had in pubs, Laois GAA county board meetings and now seemingly RTE panel shows, Twitter and on the back pages of the Sunday Independent, but on the pitches of Ireland, where sport is actually played, you'll find examples of players who have played any number of sports.

But what kind of conversation would that start?

Ireland's Grand Slam win over England on St. Patrick's Day, a TV3 executive's dream scenario, commanded a television audience in excess of 1.3 million but we also know that 1.41 million people watched last year's All-Ireland final between Dublin and Mayo on RTE, and that 1.04 million people watched the second leg of Ireland's World Cup play-off with Denmark.

Are we really going to proclaim rugby as the national sport because roughly about 159,000 more people watched Ireland's third ever Grand Slam - against England - on St. Patrick's Day - than they did an All-Ireland final?

There are GAA county board members that have likened kids playing different sports to preparing for war, and former Irish rugby internationals basing rugby's rise as Ireland's new national sport off of television ratings of one match and his conversations in a restaurant with a Polish waitress.

The conversations about which sport is the nation's sport are usually had in pubs, Laois GAA county board meetings and now seemingly RTE panel shows, Twitter and on the back pages of the Sunday Independent, but on the pitches of Ireland, where sport is actually played, you'll find examples of players who have played any number of sports.

But what kind of conversation would that start?Explore more on these topics: