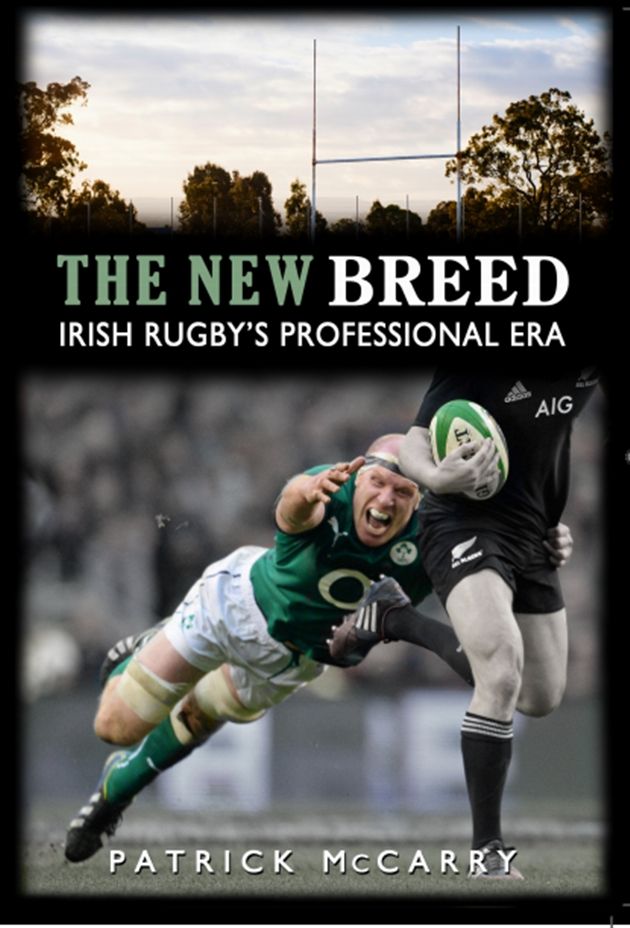

Wednesday August 26, 2015 is the 20th anniversary of rugby turning professional. SportsJOE’s Patrick McCarry has documented the remarkable transformation that has taken place in those two decades in a new book The New Breed: Irish Rugby’s Professional Era.

In this exclusive extract, Ireland and Leinster full-back Rob Kearney discusses what life is really like for the modern day pro…

…

My first exchange of words with Rob Kearney came outside the Old Wellington Inn in Manchester, on 29 August 2009. The fullback was on his final weekend off before returning to Leinster for a tapered start to pre-season. It had been eight weeks since he had lined out for the British & Irish Lions against South Africa as Ellis Park, Johannesburg, hosted the third Test. Kearney had begun the first Test as backup to Lee Byrne, but an injury to the Welshman meant Kearney was in the thick of it from the thirty-sixth minute.

The Lions lost the Test series 2–1, but the fullback was a sensation. Coming on the back of Ireland’s Grand Slam success, in March of that year, this gave Kearney a strong claim as world rugby’s best No. 15.

We were in England on separate jaunts, but for the same reason. Manchester United were hosting Arsenal at Old Trafford that afternoon. Kearney, I am sure, was as curious as I to see if Cristiano Ronaldo could really be replaced by the likes of Gabriel Obertan and free transfer drop-in Michael Owen.

As a conspicuous, proud Irishman, I prefer to leave celebrities and sports stars to their free time, especially when I am enjoying mine. I was a couple of pints into my day, however, and Kearney’s imperious performances compelled me to have my say. As we finished up our round and contemplated a fast-food lunch, I took leave of my friends and approached his beer-garden table – ‘Rob, just wanted to say you were world-class against South Africa during the summer.’

One hopes it was a nice moment on his trip to Manchester, but I suspect Kearney’s highlight mirrored mine – that of Arsène Wenger getting dismissed from the sidelines for kicking a water bottle as United emerged 2–1 victors over the Gunners.

As soon as I got the go-ahead for this book, I put Kearney’s name on an interview wishlist. He had taken over as Irish Rugby Union Players’ Association (IRUPA) chairman from Johnny Sexton after the out-half ’s move to Racing Métro. He was a season into the job by the time we eventually caught up; I was advised it would be best to confine my questions to his role and responsibilities. ‘You ask the questions, I’ll answer,’ he proclaimed after we had swapped summer-of-2014 niceties. We began with his entry into provincial rugby.

Bright start

‘I first came into Leinster for an Under-15 camp, just after third year in school and my Junior Cert,’ he said. ‘The camp was at Old Belvedere and Kurt McQuilkin was in charge. Rugby was always in my family. My dad, granddad and older brother all played at Clongowes; that was something I always wanted to do.

‘Up to fourteen or fifteen, though, Gaelic football was the major sport. I trained and played three or four nights a week, and would have had matches, in both sports, each weekend. When it came time to make a decision on which sport to pursue, rugby being professional swung it. I knew that you could make a much better life for yourself as a rugby professional than as an amateur GAA player.

‘I was so lucky coming in as I was offered a one-year deal and, within that first season, I was playing. There were very few young guys playing for their provinces at the time, so the academy lads – myself included – got a chance early on. I was 18 when I first came in, and by 19 I was playing with the first team.

‘I remember for my first weights session in the gym, with the senior team, I looked at the timetable, and I was in with Brian O’Driscoll and Shane Horgan. Your first inclination is to be awestruck, and I was a bit as I had grown up watching them on TV, men I had admired and respected. I knew I was in there for a reason and vowed to myself that I would not hold back. You have to get to grips with it pretty quickly and push yourself so it becomes a level playing field.

‘I got my chance early as Denis Hickie got injured, so I was put in on the left wing for around six months. It is different now. A lot of lads go through the academy process for three seasons before taking the step up, or not, to the senior team. Lads may get a chance now, but if they don’t perform they go right to the back of the queue. It might be months before they get a look-in again.

‘When Michael Cheika came in and offered me the developmental contract, he was very matter-of-fact about it – made it seem like my natural progression.

‘What took me aback, though, were my first couple of calls about Ireland. One was on the same day I was playing for Leinster. I got a call from Eddie O’Sullivan, who let me know I was doing well. I was just nineteen at the time. I thought, a hundred per cent, that it was a piss-take.

Kearney scored three tries in his first three senior games. He was narrowly denied a fourth against Ulster as James Topping and Andrew Trimble ushered him over the touchline before he could touch down in the left-hand corner. He was soon put forward for interviews alongside Cheika, tearing home for Heineken Cup tries and training with the Irish senior set-up. For six months his feet hardly touched the ground.

‘One of the strongest attributes that any team possesses is players looking out for one another,’ he told me. ‘When a young lad of 20 or 21 gets his first big contract, his teammates often take it upon themselves to make sure he does not get carried away with himself. Our academy system is so strong as the competition for places is so high, and it is full of lads with huge talent and ambitions.

‘One of the first things many academy graduates think when they make the senior team is, “This is great, but I want more.” That means holding down a regular spot, but aiming for Ireland, the Lions. That is encouraged, but that ambition has to be matched by hard work and dedication. That is where the senior professionals come in and keep the younger lads in line – remind them of their responsibilities. That team culture is strong at Leinster, and has been one of the main reasons for our success in recent years.’

***

Kearney can be bracketed in the second coming of professional rugby in Ireland. The academy system was not as multi-faceted as it is today. Still, thanks to the likes of O’Driscoll and Horgan, the path to a professional rugby career was clearer.

The second generation were vital in helping the province pull clear of the also-rans and become a winning entity.

‘I can’t believe the changes that have happened at Leinster since I first arrived,’ he admitted. ‘I was there for the Heineken Cup games at Donnybrook when it was not near full. Going to away games with thirty or forty fans in our section, cheering for us. The change has been enormous, and the most satisfying thing is that the trend has not reversed. Our support keeps growing.

‘That is not just down to the players but the backroom staff that are needed in any professional organisation and the fans – the ones that were there from the start and the ones that have started to follow us. It all helps in building a huge project and a successful one, too.’

The players’ union and its work with professionals away from the field, he commented, was a side of the game that always interested him. ‘We’re taking small steps in what is a big work in progress,’ he explained. ‘Some of the issues we tackled in 2014 revolved around sick pay and leave, guys getting injured and the player-development programme. Because, when they retire, it is all about easing a player back into the big, bad world out there.

‘Our job, at IRUPA, is to ease that transition and provide career options and pathways.

‘One such step in the developmental programme is the mentor scheme – teaming a player up with an entrepreneur or businessperson for guidance; giving them someone to bounce ideas off.

‘The IRFU has done a reasonable job of running the game as professional now, and ensuring that each of the provinces are in good shape – competitive. They deserve a huge amount of credit for that. The end of season [2013/14] accounts look very healthy.

The success of the national team feeds into that, so there is a vested interest in making sure Joe Schmidt and his coaching staff get what they’re after.

‘Rugby is a business now, and if you do not run it accordingly, everyone suffers.’

‘No messing about’

As rugby is a business, Kearney sees first-hand how players are commodities, but warns against heaping on further physical and mental demands. ‘Players are training and playing now for eleven months of the year,’ he said. ‘We get four weeks of holidays, and we use that time to unwind a bit. Some lads might spend a good few quid here and there, but you are always conscious of not getting too carried away, or letting yourself go, or it will be harder on you in pre-season.

‘Once you’re back, you’re back. No messing about.

‘I can tell you exactly where I’m going to be every day for the next eleven months. Everything is mapped out for us – diet plans, training, extra gym and weight sessions, matches, club commitments and appearances. It is that regimented.

‘The spectre of injuries is never far away, and is a pretty frightening one too. Anyone can succumb to a career-ending injury at any stage. There are fears about the next contract, too. It will happen to us all eventually; we won’t be offered a new contract. Only the rare few get to walk off on their own terms.’

France & Top 14

‘We are getting into dangerous territory now,’ Kearnery continued, ‘as Irish provinces will never be able to compete with France. The Canal Plus television deal (€355 million for five years’ broadcasting rights) is going to elevate their game even further. Ireland will never be able to repel all of their advances.

There has been talk of bringing in private investors, but, the way our game is run, it will not be like France with entrepreneurs and billionaires throwing money out here and there. It won’t be a case of an investor going, “Here’s a million. Off you go and spend it as you please.”

‘The IRFU’s job is to make it as attractive as possible for a player to remain in Ireland. Of course, money will come into it, but there are other aspects that they hope will make up for the financial differences. That includes the best medical care and support, world-class facilities, provinces competing at the very top end of the European game.

‘Speaking for myself, I have a huge allegiance to Irish rugby and to Leinster. I have been in the Leinster set-up since I was fourteen. At the same time, if a player feels he is doing a job and is not getting the recognition for that, or feels devalued, that is a major factor in looking to move on. No one likes feeling undervalued.

‘That’s not just in sport. The same, I’m sure, applies in banks, offices, businesses. It’s human nature. Once that value reflects in how much they are getting paid, most players will stay and set about proving themselves all over again. There are one-offs, though, where players are valued at clubs, but simply move on as an offer is too good to refuse.

‘Players are well aware of the ruthless and fickle nature of sport – they see talented teammates not offered new deals, injuries taking their toll – and that influences their decisions when contract talks come about.’

Highs and lows

Our discussion had bled past the hour mark, so, conscious of his regimented schedule, I attempted to extract Kearney’s reason for being: eleven months of a season, seeking to take the final bend at enough pace to edge home ahead of the rest; when you do, the clock is re-set and you go again; when you fail, the clock is re-set and you go again.

There was silence on the other end of the line.

Then he said, ‘The highs in rugby are unbelievable. When you win, there is no better feeling in the world.

‘When you win a trophy and you’re back in that dressing room, surrounded by your friends and you’re all so spent – there is a feeling of such intense joy.

‘And the lows are unbelievably low. If you have a bad day at the office, you can often leave it behind at 5.30 p.m. If you have lost a match or are in a rut of bad form, that stays with you for weeks, twenty-four hours a day.

‘Then you have times when you are out of favour, the injuries and the times where you can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. I was lucky, in a way, to have some injuries early in my career, so I knew how to cope with that feeling of frustration – helplessness.

‘But you will go through months and months of the setbacks, the crushing disappointments, the lows.

‘You will go through it all just to feel those one or two moments of pure joy again.’

This extract was taken from The New Breed: Irish Rugby’s Professional Era (Mercier Press), by our very own Pat McCarry. The book is being officially launched at Hodges Figgis, Dawson St., Dublin 2 from 6pm this evening. Copies are available to buy here.