Share

1st March 2017

07:31pm GMT

Men who looked like minor characters in the Asterix books wandered through the lobby in search of a drink, a cup of tea and a chat about the motions. It was Friday night, everyone had just left headquarters and crossed the road to the Croke Park Hotel. Congress 2017 was only getting started.

One delegate told me a story about a man who wandered into congress on a Saturday morning still disorientated from the Friday night.

A friend looked at him.

“Jaysus, Peter, your eyes are a mess.”

“You should see them from this side.”

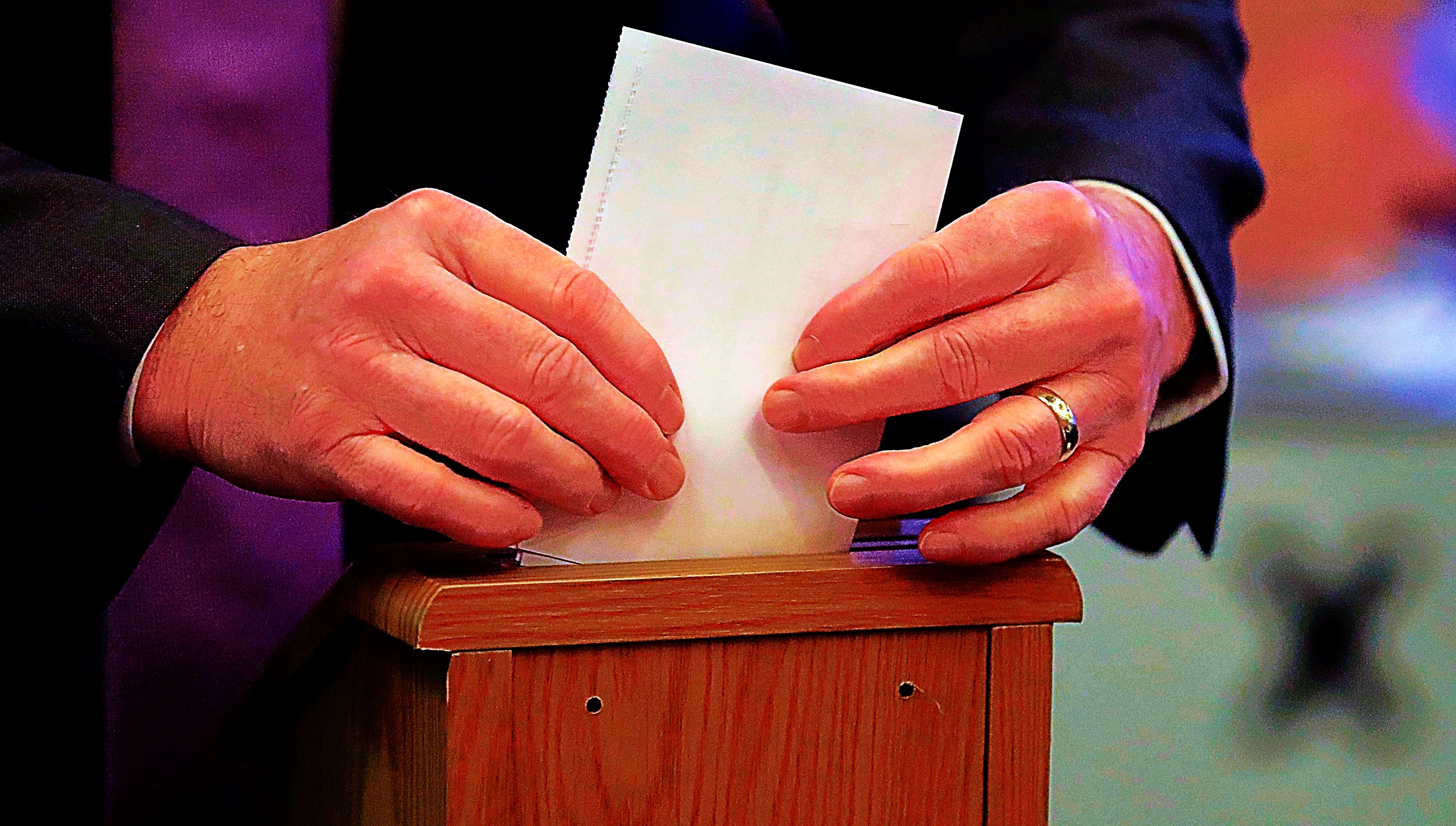

Earlier on Friday, John Horan from Dublin had been elected the next president of the GAA on the first count. They use proportional representation to elect the president. “Please use numerals, do not use an ‘X”,” it was stressed from the top table. This might have been especially necessary for those from Northern Ireland, as nobody at congress would call it, and the UK. “A special welcome to the delegates from the province of Britain,” they said when the people from the UK were introduced.

And at Congress, it is all logical. For two days, there is this sense within the building that everything including Britain - hell, especially Britain - is subordinate to the great volunteer machine that is the GAA.

Perhaps this sense is even more pronounced when congress takes place at headquarters, the stunning stadium that is sacred ground, while also being a monument to the commercial strength of the GAA.

The delegates mandated to vote on the motions that would define much of the GAA’s work were here to exercise that mandate. They might do more as well and get it all wrapped up before congress mass on Saturday evening.

On Friday, nobody had seen Horan’s victory coming. He won on the first count and when it happened, the place had gone absolutely fucking crazy. By absolutely fucking crazy, I mean there was a noticeable increase in murmuring and a vague sense of disorder as if a bridesmaid had vomited on the altar while the bride and groom were exchanging their vows.

Horan had received 144 votes, his nearest challenger got 46 and all that was left for the losers was a night trying to figure it all out.

The president-elect became emotional as he spoke. He thanked his wife for her support and looking “after the home affairs”. He mentioned the credo of his club which had something to do with purity in your heart and strength in your limbs and everyone in the hall instinctively knew they were in safe hands.

I thought this victory was big news. I had accidentally interviewed one of the candidates earlier in the hotel. Robert Frost said it was a bit of a lottery and there were some hurdles to clear. Later, I was told that nobody except the presidential candidates and maybe people from their counties really care who is president.

After the result, I found myself standing beside a man at the back of the hall.

“Dublin are taking over,” I said to him because I'd just heard someone else say it.

“They surely fucking are,” he laughed, but he didn’t seem too worried about it.

Horan will become president next year, but that wasn’t considered too important. I kept bumping into Robert Frost, who was a lovely man and listened to me babbling away with questions and observations.

At one point I came across him sitting on the steps up to the media area so I gave him a consoling pat on the shoulder which I don’t think he needed.

“We’re streaming now on W W W, dot, GAA dot I E,” it was announced before the vote was taken. The internet was out there, watching, but they would do things in the best interest of the association, not because the internet was watching.

“It’s difficult to continue after all of that,” Aogan O’Fearghail, the current president, said after Horan’s speech and the drama of the vote. He decided to wrap things up for the evening.

But congress was only beginning. On Friday night, they talked about the 56 motions that were part of Saturday’s agenda. The powerful figures in the association were lobbied for their views. Jarlath Burns and Frank Murphy, the secretary of the Cork County Board, sat in a corner of the Croke Park Hotel discussing the Super 8 proposal.

This was the key motion, the one that would bring historic change to the GAA. Cork would vote against, finding themselves in the strange position of being on the same side as the GPA. This was a gathering for volunteers, a testament to the strength of the amateur ethos, but it wasn’t hard to pick up the hostility towards the GPA, the CPA and others who try to make a case for one section of the membership.

The GPA had made the headlines all week and there seemed to be some concern that there would be a struggle to win the vote on Saturday.

“We all have imaginations, otherwise we wouldn’t be in the GAA”

Saturday began with an announcement that the bus bringing delegates from the Gibson Hotel was running late, and then a further one that “we have to get accustomed to using our zappers”. They ran a test of the voting machines - ‘Is Croke Park in Dublin?’ 78 per cent voted Yes, 22 per cent said No. Everyone laughed and then they got down to the business of shaping the GAA and maybe the business of shaping a nation.

Congress travels the country, but this year it took place in headquarters and perhaps Croke Park was the best place to be when making these historic decisions. If the GAA sees itself as the organisation which, more than any other, has shaped Ireland, maybe the modern Croke Park represents their ability to command ongoing relevance when the other great powers -the Catholic Church and Fianna Fail - have diminished or struggled.

But in remaining relevant, what have they done to their core values? “We earn as much as we can to distribute as much as we can,” the association’s finance director said on Friday night and this is the organising principle of the GAA. Even people I know who can’t stand the GAA consider it one of the great volunteer organisations in the world.

But the GAA now inhabits a world where they can earn more than they ever could before. They know this too. They appeal to all sections of Irish society which makes them attractive to more brands than any other sporting organisation. On Saturday evening mass was said in the Players’ Lounge below ground level at Croke Park. The Players’ Lounge can also be hired for corporate functions.

Amateurism is the beating heart of all of this. At its worst, amateurism allows some GAA supporters to feel superior to sportspeople - usually professional footballers - while embracing other forms of cultural nationalism as well.

At its best, amateurism connects the kids playing on an artificial pitch in west Cork on a Tuesday evening in February to those stars who walk out at headquarters on the third Sunday in September (at least until 2018). They are all the same, making sacrifices for the good of each other, the association and Ireland. Nearly everyone believes that the ties that bind the GAA community will protect it, that the story the GAA tells about itself will always triumph, no matter how much things change.

They believe they are wedded together, looking out for each other no matter what, whether it is an uncle visiting a nephew asking him to play one more game of inter-county or Croke Park helping out a club in financial difficulty. All of this is dependent on amateurism which is why it will never be abandoned.

Common welfare is an idea delegates take seriously because it is the most fundamental. The first motion passed on Saturday prohibited players, management and officials from betting on any game they were involved in.

The debate was a powerful and informed explanation of the dangers of gambling to young people, the GAA and wider society. It was “a silent killer”, one delegate said, that devastates the victim “as much as any other addiction”. 234 delegates voted to pass the motion. Two used the privacy of the zappers to vote against.

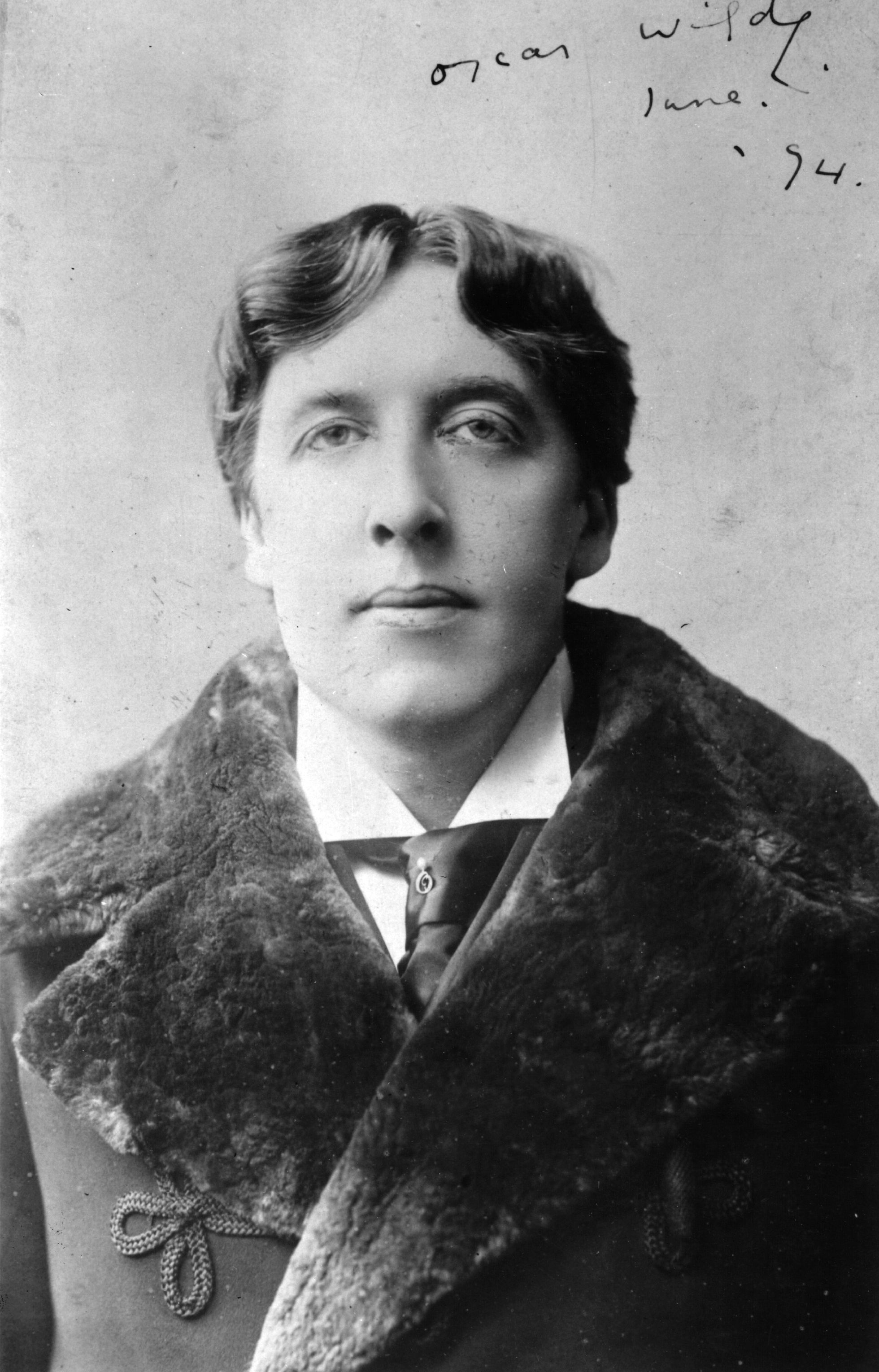

And then we came to the big one. This was the equivalent of draining the Shannon someone said. Oscar Wilde’s line about knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing was mentioned, starting a theme of delegates quoting Wilde or, more exactly, mentioning how many times previously Oscar Wilde had been quoted before going on to quote somebody else.

The Super 8 wasn’t a silver bullet, someone said. Another insisted it wasn’t the golden bullet. But the message from the hall was clear: the important thing was they loaded the gun.

“We shouldn’t be afraid of change,” one delegate said.

“It’s time for change,” somebody else said.

“We are often accused of being reluctant to change,” someone else said.

It may not have been as monumental as allowing soccer and rugby to be played at Croke Park, but speaker after speaker warned delegates they shouldn’t let this opportunity slip. As this was happening, there was anger erupting elsewhere. On Twitter, players spoke out against the decision. This great obstructionist force in Irish life had drawn rage from the modernist wing for embracing change. This was the wrong change, this did nothing for the players and asked them to do more. “There are other ways to deal with burn-out,” another delegate said.

The Cork delegate who spoke against the motion wasn’t sure if there was. “There’s one group that has not been discussed at all, and that's the players…I would ask our delegates to consider the welfare of the players and the amount of trauma they would put their bodies through to play three matches in 15 days.”

Only Cork and the GPA spoke against. O Fearghail looked for more opposition from the floor and there was none.

We moved to the vote. “With the wisdom of Oscar Wilde in your thoughts,” O Fearghail said as he turned the process over to the wisdom of the zappers.

The result seemed inevitable given the mood in the room but the disconnect seemed clear as well. 70 per cent of GPA members had voted against the proposals; 76 per cent of delegates voted in favour. And with that, they moved on to fundamentally altering Sundays in September.

The delegates were in no mood to cleave to tradition and 78 per cent of them voted to move All-Ireland finals to August on a trial basis. This was the GAA embracing radical change. From 2018, the All-Ireland finals won’t take place in September. This move, designed to help club players, also suggests that nothing in their calendar is sacred, that everything can be reshaped, most crucially the championship.

The third part of the trinity - abolishing replays except in provincial and All-Ireland finals - received 91 per cent approval.

The rest of the morning passed in a blur, not of excitement, but of a strange intersection of boredom and fascination.

By the time, O Fearghail stood up to make his speech, boredom had won and I was clutching my lunch voucher which had kept me going through motions 5-35 inclusive.

The words of another journalist provoked a feeling of deep sympathy for all those who had gone before. “Imagine what this was like before the internet,” he had said. As O Fearghail spoke, I journeyed to this happy place, the part of the internet taken up with quizzes and audio of Mark Lawrenson and Guy Mowbray being catty in 2010. In the background, I heard O Fearghail say something about upskilling.

He concluded his speech by referencing Oscar Wilde, but only to say he’d prefer to quote Parnell as he rolled out the “no man has the right to fix the boundary to the march of a nation” line. And with that we broke for lunch.

“The Proclamation beats poor ould Oscar any day.”

In the best traditions of volunteerism and egalitarianism, there were no demarcations for lunch. Delegates and journalists sat together in another fine suite at the Canal Road End eating well in the knowledge that shortly we would return to the motions and the world would turn very slowly again.

I had been lulled into a false sense of excitement by the first couple of sessions. The presidential vote on Friday night was supposed to go on for two hours, but, because of the landslide, it had been taken care of in record time.

The giddy air had been contagious too as was the general sense of welcome. There was, contrary to other events of this nature I’ve attended, less distrust between delegates and the media. Under this roof, it was assumed we were all Gaels of one kind or another.

“Well done to you,” someone on the top table said to what was described as a “native-born Lancashireman” when he had spoken Irish. He then got a round of applause from the delegates.

In this spirit of generosity, we were all going to get along, even those of us who wondered why a translation wasn’t being provided when delegates occasionally broke into Irish.

But Saturday afternoon was another test of stamina and boredom thresholds . “This will be a retrograde step,” a delegate thundered at some point, and I tried to figure out where we were and what they were talking about. A series of motions were before congress looking to reduce the majority needed to pass a motion from 66 per cent to 60 per cent.

This was fiercely debated. Brexit and the dangers of a simple majority were noted. Later someone would say that this was a vote of real significance, but I was beginning to understand that congress is always in the business of making historic decisions because that is part of the mission it has set for itself. The self-renewing idea that nobody can fix the boundary on the march of the GAA nation is an essential part of its story.

There was still time - there was always more time - for another one of those raised murmurs which made me think there was something happening here. It happened for Horan’s election, it happened when the Super 8 motion was passed and it happened when the motion calling for recognition for the CPA was withdrawn. The murmur seemed like an injection of anarchy before everything swiftly corrected itself.

“Nickey Brennan knows his stuff,” somebody said to me about the CPA murmur. I said he did, but I didn’t know who Nickey Brennan was or what his stuff was so I was at a disadvantage straight away.

Yet the hostility to the CPA was apparent even to an idiot like me. “We don’t know what their agenda is,” a delegate said when they discussed the motion that would have seen the Club Players’ Association recognised as the official representative body for club players. The delegates were here representing and yet they were discussing other representative bodies.

It is an understandable position if you are a GAA delegate who believes in the GAA. After all, the association claims to understand Ireland like no other body so why would it need another association to provide insight into how its own members are feeling?

As the CPA was discussed people again referred to the previous quotes of Oscar Wilde as if someone had put on a version of Lady Windermere’s Fan earlier in the day. This time the speaker pivoted away from Wilde to quote the proclamation which earned widespread approval.

“The Proclamation beats poor ould Oscar any day,” O Fearghail said from the top table.

Nobody thought of quoting the most appropriate line of poor ould Oscar that the trouble with socialism is that it takes too many evenings.

These were people whose evenings, weekends and much more had been taken by the GAA and they saw no reason why they couldn’t represent everyone in their club. The motion looking for recognition was withdrawn.

By now, it really felt as if it should end. There had been talk that the Ireland rugby international which started at 4.50 would add a bit of urgency to proceedings, and I gave thanks for the diminishing, if not disappearance, of inter-code enmity but couldn’t detect much urgency all the same.

The day ended with a long and informed debate again about the motion which would allow 16-year-olds to play adult matches.

Again, the best of the GAA was present as they wrestled with conflicting concerns: the welfare of 16-year-olds versus the plight of rural depopulation, something that few people care about the way the people in the GAA care about it. The motion failed.

By now the end was in sight. We were reminded that mass would be held afterwards and then the last motion was withdrawn.

https://twitter.com/dionfanning/status/835532583295455232The priest, we were told, had another mass in East Wall at 5.30 so he would be starting promptly at 4.50. The room was energised by this as generations of Irish people have always been energised by the prospect of a fast Mass.

Traditionally the national anthem had been sung by Joe McDonagh, the Galway hurler and past president who died last year. Nobody could replace McDonagh so the delegates turned and faced the flag and sang the anthem together.

They had remembered those they had lost like McDonagh and they had made decisions which will shape the association for some time to come.

Yet the GAA has changed and the weekend saw it change further. They have a television deal with Sky which has been condemned for taking their games behind a paywall. From 2018, Sky will have more games and better ones to show its subscribers.

In a world where more demands are made from managers and players are expected to be quasi-professional, they may one day reflect on the unintended consequences of altering the calendar, of accelerating the process where greater demands were made on players.

If players end up playing more and more games, how will their welfare be protected? If they can't take it, will the GAA, its sponsors and rights holders be content if these players quit?

“Like most people in the room, I am a traditionalist,” one delegate said without fear of contradiction on Saturday. And most people believe these traditions will protect the GAA while ensuring players never make demands which go against the key tradition.

Over the weekend, the GAA remained true to some of those traditions and embraced some more recent traditions such as pissing off newer bodies like the GPA. “We’re not going to run the GAA by Twitter,” Paraic Duffy said on Saturday, but if the opposition from the players is legitimate - and some have questioned the GPA’s approach - then it is more than just Twitter.

I could say I was thinking about these things on Saturday but really I just wanted to get home. I considered going to mass but felt there were things I couldn’t do as an interloper. Instead I walked out to my car on Jones Road and found it had been clamped, which felt like a metaphor for something.

https://twitter.com/dionfanning/status/835539051918811136All weekend, people had been sharing congress stories with me all and they all involved someone rigid with boredom trying to escape. Now I would have to stay a little longer.

My favourite story was about the work experience kid who came into a newspaper thinking he’d be part of the exciting business of sports journalism, but instead found himself dragged along to congress wondering what this - and maybe even life - was all about. Inevitably, soon he fell asleep.

This was too much for one delegate who elbowed him sharply and told him to wake up. He was missing history being made.

History is always being made at congress, you soon learn that, but the kid opened an eye, looked around the room of men speaking about motions and traditions and wondered if this history was his nightmare or his reality. He heard them talking about Ireland and change and how this is an organisation concerned with the vision of a nation, and he took the smartest move available to him. He went back to sleep.

Dion discusses his Congress experience on the GAA Hour. Listen below or subscribe on iTunes.

Explore more on these topics: