Before going into the smaller detail in this game, it’s worth noting that both sides were meticulous in two elements which Dublin, Mayo and Kerry haven’t been over the last two seasons.

Firstly, only once throughout, did a player on either side, win an easy break under the midfielders where he didn’t have an opponent within arm’s length, or have to take a physical hit in order to come away with the break.

Secondly, until an injury-time consolation for Donegal, each side conceded a mere point each from frees. Both of these elements allude to highly-structured set-ups.

Of course, when you’ve conceded 1-21, that record doesn’t stand for much. At a score concession of 1-12, it’s noteworthy.

When this game was pulled apart and sliced and diced into different segments, the conclusion is that Rory Gallagher simply doesn’t appear to have the raw materials to match Donegal’s recent achievements.

Quite simply, as we’ll see, the side with the greatest amount of raw ability won.

Score Analysis

Because it’s quite difficult to quantify what constitutes it, I’m wary about compiling statistics which look at how many times individuals have tried and succeeded or failed in taking on opponents, man-on-man.

Within arguable parameters, however, Tyrone appeared to have done so 17 times to Donegal’s eight.

What is quantifiable, however, is looking at how the key line-break was made for the sides’ respective scores. The ability to take on and beat the respective opposition directly is striking.

Excluding an injury-time consolation free, from Donegal’s 1-11, the key line-break for 1-5 came off the back of the line-breaker taking the ball off the shoulder at pace. A further two points came in similar fashion off the back of a “one-two”, with another coming off the back of the “one-two-three” (a man receiving the hand-pass and shifting it quickly to a third man). One came from an unnecessary foul by Tyrone, while two more came from “picking and poking” their way around the Tyrone defence for long enough for a man to find himself in enough space to kick an uncontested point.

Until the 75th minute, not one score came from a Donegal man staring a Tyrone defender in the face, taking him on and beating him/forcing a free.

Similarly, Tyrone scored nine points where the key line-break was made taking the ball off the shoulder, and three more from “pick and poke” play.

He's completely reinvented the game… againhttps://t.co/1qLpnlcFcY

— GAA JOE (@GAA__JOE) June 18, 2017

However, 1-10 came off the back of a Tyrone man taking on and beating a Donegal man directly, including one which forced a free.

For seven of these points, Donegal were set up perfectly well with a defensive shape you’d have to assume Rory Gallagher would have been happy with, with Tyrone in static possession outside the front line of their zonal defence. Tyrone players, however, simply stared them in the face, took them on man-on-man, and scored or created the score.

While the line was initially broken for their goal by Tiernan McCann, it was his ability to take on and beat Karl Lacey which put him through one-on-one with the keeper.

Also noteworthy is that these 11 scores were accounted for by seven different individuals – Mark Bradley twice, Tiernan McCann twice, Peter Harte twice, Niall Sludden twice and each of Mattie Donnelly, David Mulgrew and Kieran McGeary once each.

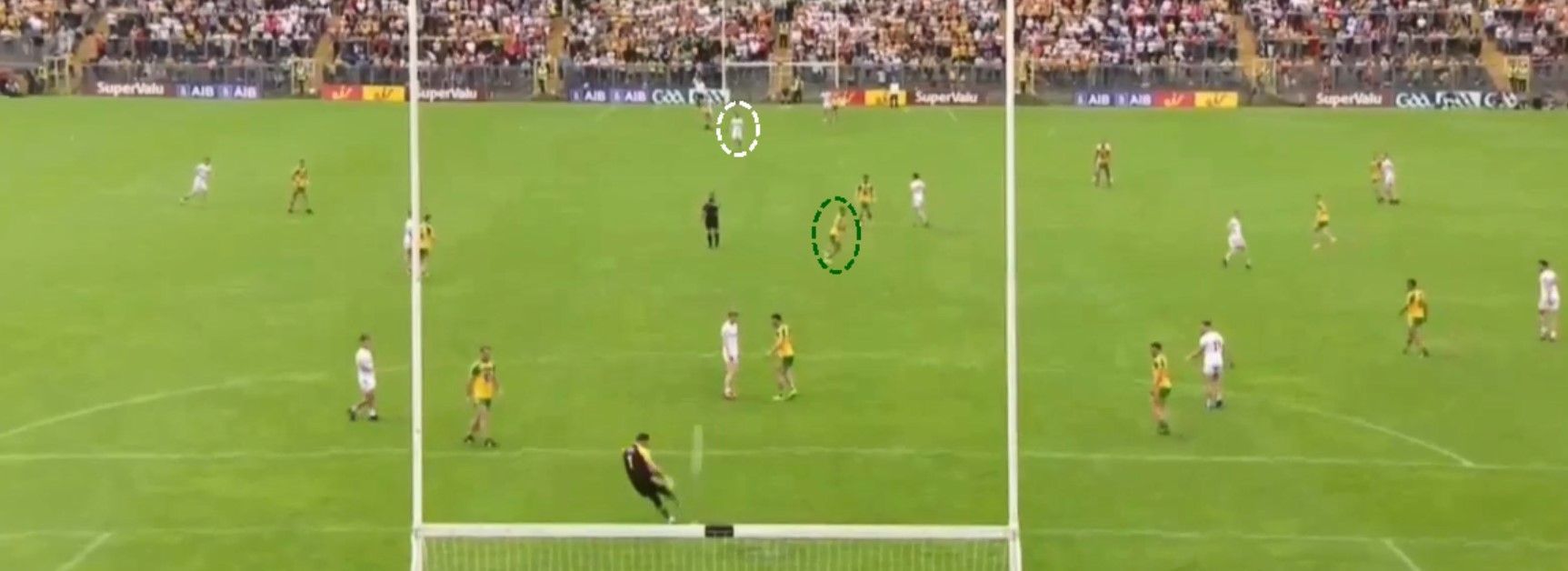

The most noteworthy of these line-breaks was made by an eighth, Seán Cavanagh, but the goal chance he created wasn’t converted.

Donegal were well set up with three spare men when Cavanagh took possession

But he took on and beat his man

And cut through the entire Donegal defence to directly set up the goal chance

With two sides who are probably as well set up and structured as you’ll find in the country, the simple difference was the respective raw ability to take on and beat the opponent individually.

Zonal Defence Analysis

Another striking element was the manner in which the two sides launched attacks.

Coming in at a significantly higher proportion than average, the large majority of the time both sides attacked, they faced a zonal defence.

Measuring an attack as crossing an imaginary, curved line, 60 metres from goal, in possession, Tyrone had 44 attacks and Donegal 41.

Tyrone were forced to attack into a zonal defence on 36 of those 44 occasions. Startlingly, Donegal were forced to on 40 out of 41 attacks!

Those figures are telling, in their own right, in Tyrone’s favour, but the reasons are of more interest.

Making the most logical and rational use of space, neither side tried to press the opposition in the middle third, where you’re only likely to be “piggy in the middle” by a numerically superior side in that area of the field.

Both sides are systematically simply turning and jogging/three-quarter pace running back to behind their own “65” and letting the opposition try to break them down there.

With the exclusion of three short Donegal kick-outs which went astray/were thrown in by the ref, neither side overturned the other in their defence from start to finish.

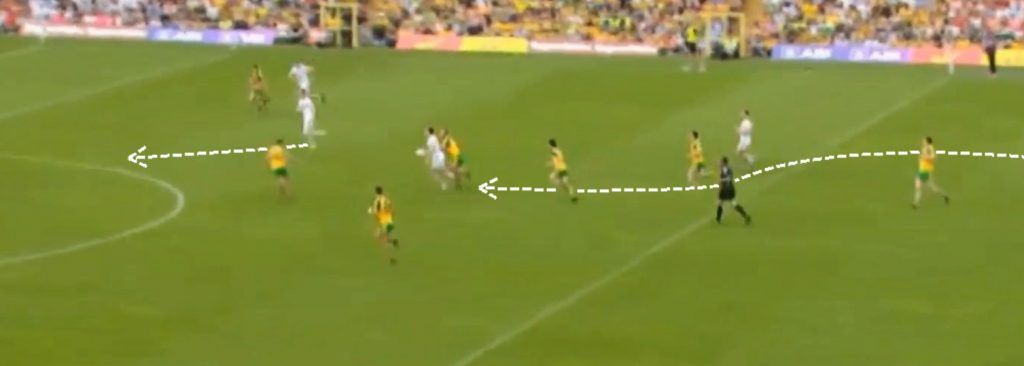

Seven Tyrone defenders ignore the ball and track into a zonal position

![]() And it’s the same the other way as eight Donegal men track back

And it’s the same the other way as eight Donegal men track back

The overall figures show that Tyrone managed a highly impressive 50 percent score ratio of 1-15 from 36 attacks into a zonal defence, while Donegal managed a 37 percent ratio of 1-12 from 40.

Tyrone’s Attack

The key question is, how did Tyrone manage to create four man-on-man attacks and one overlap while Donegal only managed a single man-on-man attack?

The larger part of that equation is answered by the initial section here. If you can take on and beat opponents directly in the middle third, you have a greater chance of creating a man-on-man attack before the opposition set up a zonal defence.

The second issue, however, was Tyrone’s shape. Unlike most teams who tend to get their whole team behind the ball on various occasions, Mark Bradley, before he was scandalously black carded, held the full-forward position almost religiously.

On a number of occasions, though maybe less than would be ideal, Tyrone had a man sitting in the centre forward position too. This meant that when they turned Donegal over at the back, they had the option of playing quick ball forward and attacking before Donegal got men back.

Donegal come under pressure against a 12-man zonal defence and get turned over

But Tyrone’s shape allows one pass to take out six Donegal men

Where Seán Cavanagh was man-on-man at centre forward

Even after being fouled, one more pass and can take out six defenders again

Darren McCurry shoots wide, but received the ball man-on-man in acres of space

It’s a key strategy that seems lost on most teams. Ironically, amidst a chorus of anti-blanket defence rhetoric in the noughties, keeping two and three up-front almost at all costs was key Mickey Harte’s success back them. If they’re to win an All-Ireland, maintaining this attacking shape will be again.

Colm Cavanagh

It would probably have been impossible to spot from TV, but the manner in which Colm Cavanagh played as sweeper was as well applied as I’ve seen and was at the crux of why Donegal only managed one man-on-man attack throughout.

He shifted seamlessly between positioning himself at midfield for kick-outs, then dropping back into the sweeper role at the right time, and even occasionally taking up a man-marking role in the full-back line to allow a better-positioned player to push up as sweeper, when the need arose.

It allowed Tyrone to keep an ideal defensive shape throughout. Furthermore, when he was in a sweeper role, as I’ve come to expect from all Tyrone senior and minor teams, he played the angles methodically, knowing when to kill the space, and knowing when to double up on the man.

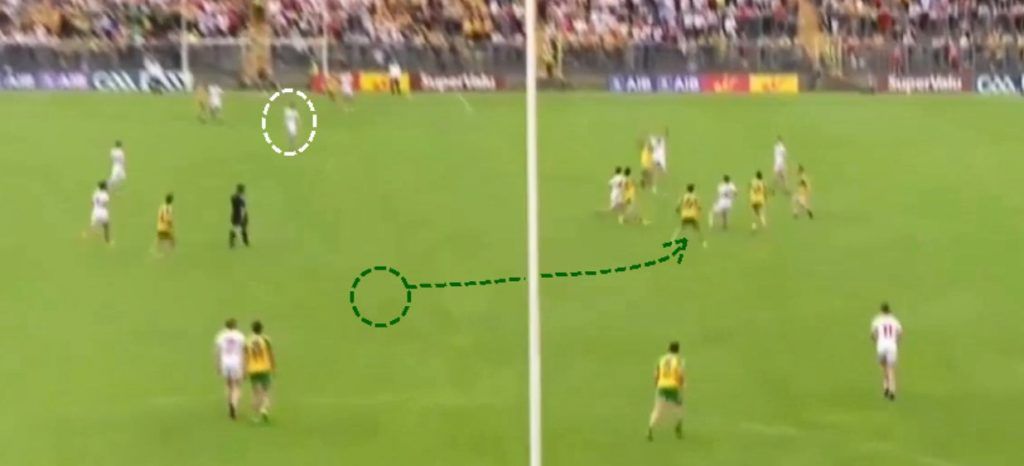

Cavanagh was at midfield for the kick-out, but orders affairs from there

And held the line watching two attackers

But still managed to drop off into the key space after the ball was played

It does raise question marks about the policy, as to whether you’d be happy to let Cavanagh drop into the full-back line and pick up a Bernard Brogan or James O’Donoghue. Notably, he was the only man on the Tyrone side to give away a scoreable free, while man-marking from full-back.

On the day, however, his meticulous understanding and application of the role made him worth his weight in gold.

Kick-outs

There were two tactically noteworthy patterns on the kick-outs in Clones.

Most significantly, Tyrone’s sole over-lap attack and Donegal’s sole man-on-man attack, both came from the source.

As team after team around the country copy Jim McGuinness’ tactic of 2014 against Dublin, and try to push up high on the kick-out, the long kick-out over the top is becoming more and more of a central tactical key.

Sides are trying to apply zonal defences, but at the same time, they’re pushing up high on the kick-out. There’s somewhat of a contradiction there. Win a long kick-out over the top and there’s every chance you’re in for a goal. Both sides managed it once in Clones, even with Tyrone holding their sweeper on Donegal’s kick-outs.

There were acres of space behind the fielders on the kick-out

Image 6 B (which Donegal exploited when it broke behind the fielders)

The second striking pattern was the manner in which Donegal applied their spare man on the kick-out as Tyrone left a sitting sweeper.

The spare man didn’t go wide and look to spread Tyrone so they could get off a short one. Donegal instead, presumably with breaking forward at pace off the long kick-out in mind, tried to win them long and break from there.

To that end, their spare man sat in the middle and tried to become the spare man on the breaks.

The spare man held the centre, with Tyrone’s sweeper at the back

And then got in under the break

Despite this, Donegal still only won two from five of their long first half kick-outs and conceded three points off the five they lost. They conceded four points to one in total off their own long kick-outs.

That they drew even at four points scored and four points conceded upon the first turnover on their own kick-outs – hit both quickly and not – suggests that the free man trying to get the short kick-out might have worked out better.

Conclusion

All in all, however, the fact of the matter is this. Since Donegal won the All-Ireland in 2012, they’ve lost six key players, and a seventh, 2014 All-Ireland finalist, Odhran MacNiollas, isn’t playing, while an eighth, Karl Lacey, is 33 this year.

All patterns from this game suggest that with two of the most systematically organised and well-structured sides in the game, Tyrone simply have significantly higher levels of raw ability.