Share

15th November 2020

09:52am GMT

More isn’t necessarily better- quality is critical. You have a limited amount of time and energy to practice so it is prudent to make the best use of it. Effort and strategy are key. Some athletes often fall into the trap of being ‘too busy training to practice’. This is a time management issue and can be addressed (see Chapter 21). Individual practice is essential.

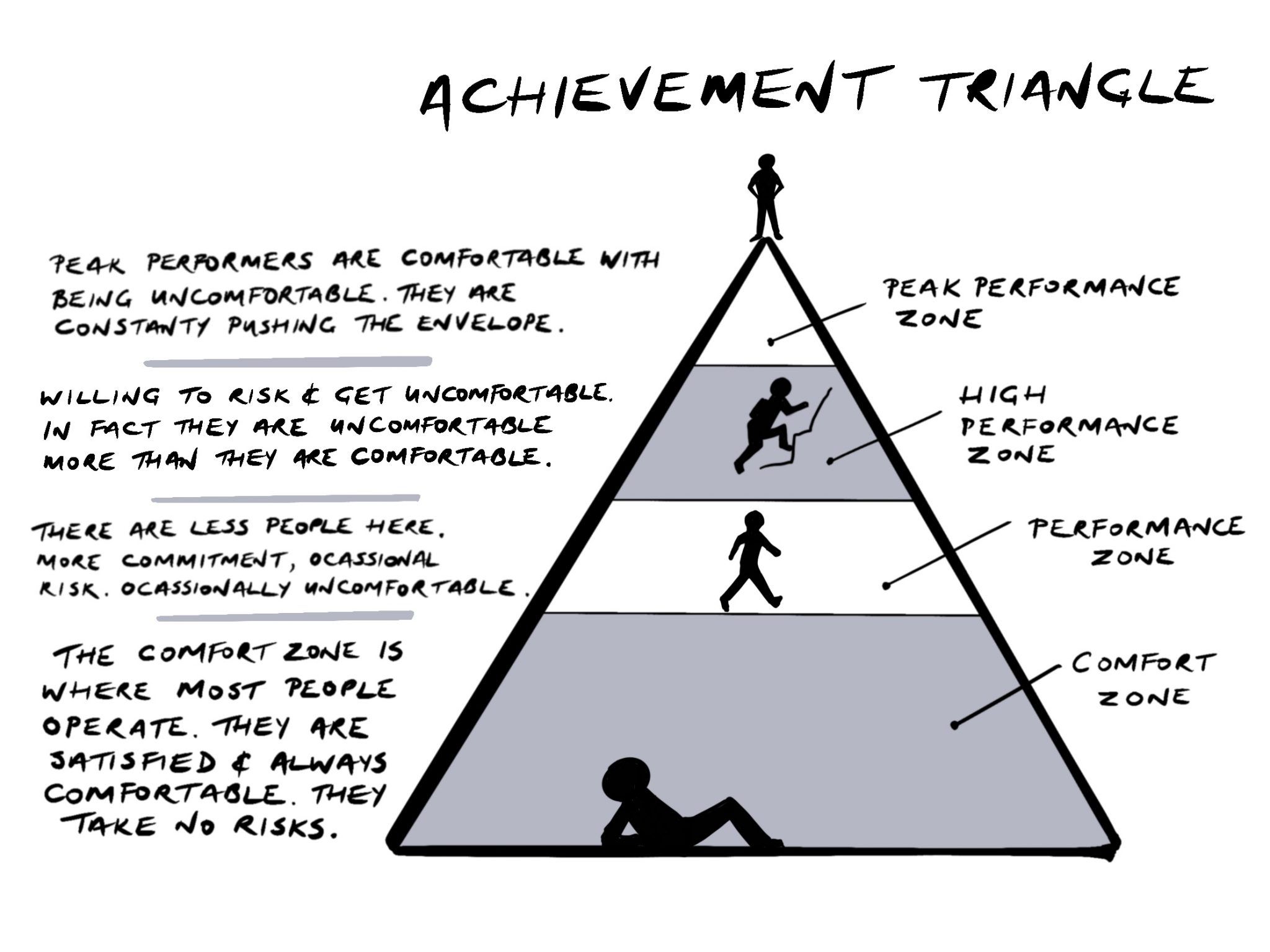

Though perfection is unattainable, aiming high allows you to surpass your own preconceived limitations. Run from your comfort zone. Aim for perfection; deliberately practice the core skills of your game. Get uncomfortable. Strive to be ‘brilliant at the basics’. In the basics, attention to, and mastery of, tiny details are commonly overlooked. Do the simple things better! How close can you get to perfect?

As with most things in life, effort is important but so is strategy. If you focus your practice, while maximising your application, with time, the repetition will create momentum and this momentum will produce improvement and better performance. The key to effective practice is to make it purposeful and deliberate. Understanding the demands of your sport and the role or position you play, as well as learning how to properly analyse your performance (see Chapter 7), will help inform you of what parts of your game you need to focus on.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate Practice is based on the research of K. Anders Ericsson. It refers to a special type of practice that is purposeful and systematic. For example, if you were a full back in rugby and high catching was something you struggled with, you would purposefully and systematically practice to address this. High catching would be one of your ‘work ons’ and could be done before or after collective training with the aid of a teammate or coach. Visualisation techniques (see Tony Óg’s Skill No. 3) could also be used to assist the process.

Deliberate Practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance. It differs from ‘regular practice’ in that regular practice might largely consist of mindless purposeless repetitions.

"Excellence demands effort and planned deliberate practice of increasing difficulty" - Anders Ericsson

The goal of Deliberate Practice is not to be enjoyed. Its only goal is to improve your performance. However, I feel this is not to say it cannot be enjoyed by those with the correct mindset and outlook. Satisfaction is to be gained through application and learning, and this should be embraced and viewed as enjoyable. Deliberate Practice requires sustained effort and concentration. It requires the learner to continuously challenge themselves, set goals and practice at the edge of their current ability. Too easy, and there will be no learning. Too hard, and there will no opportunity for feedback and improvement. Remember, when you do what is easy in life, life becomes hard; when you do what is hard, life becomes easy.

The greatest challenge of Deliberate Practice is to remain focused on improvement. The more we repeat a task, the more mindless it can become. Mindless activity is the enemy of Deliberate Practice. Feedback is essential. Measurement is one means of feedback. What we measure we improve.

Example of Deliberate Practice in Hurling:

Key Focus Skill- Striking off both left and right hand side. Secondary Skill- Catching

More isn’t necessarily better- quality is critical. You have a limited amount of time and energy to practice so it is prudent to make the best use of it. Effort and strategy are key. Some athletes often fall into the trap of being ‘too busy training to practice’. This is a time management issue and can be addressed (see Chapter 21). Individual practice is essential.

Though perfection is unattainable, aiming high allows you to surpass your own preconceived limitations. Run from your comfort zone. Aim for perfection; deliberately practice the core skills of your game. Get uncomfortable. Strive to be ‘brilliant at the basics’. In the basics, attention to, and mastery of, tiny details are commonly overlooked. Do the simple things better! How close can you get to perfect?

As with most things in life, effort is important but so is strategy. If you focus your practice, while maximising your application, with time, the repetition will create momentum and this momentum will produce improvement and better performance. The key to effective practice is to make it purposeful and deliberate. Understanding the demands of your sport and the role or position you play, as well as learning how to properly analyse your performance (see Chapter 7), will help inform you of what parts of your game you need to focus on.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate Practice is based on the research of K. Anders Ericsson. It refers to a special type of practice that is purposeful and systematic. For example, if you were a full back in rugby and high catching was something you struggled with, you would purposefully and systematically practice to address this. High catching would be one of your ‘work ons’ and could be done before or after collective training with the aid of a teammate or coach. Visualisation techniques (see Tony Óg’s Skill No. 3) could also be used to assist the process.

Deliberate Practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance. It differs from ‘regular practice’ in that regular practice might largely consist of mindless purposeless repetitions.

"Excellence demands effort and planned deliberate practice of increasing difficulty" - Anders Ericsson

The goal of Deliberate Practice is not to be enjoyed. Its only goal is to improve your performance. However, I feel this is not to say it cannot be enjoyed by those with the correct mindset and outlook. Satisfaction is to be gained through application and learning, and this should be embraced and viewed as enjoyable. Deliberate Practice requires sustained effort and concentration. It requires the learner to continuously challenge themselves, set goals and practice at the edge of their current ability. Too easy, and there will be no learning. Too hard, and there will no opportunity for feedback and improvement. Remember, when you do what is easy in life, life becomes hard; when you do what is hard, life becomes easy.

The greatest challenge of Deliberate Practice is to remain focused on improvement. The more we repeat a task, the more mindless it can become. Mindless activity is the enemy of Deliberate Practice. Feedback is essential. Measurement is one means of feedback. What we measure we improve.

Example of Deliberate Practice in Hurling:

Key Focus Skill- Striking off both left and right hand side. Secondary Skill- Catching

I played hurling. The technical demands of the game are huge. The simpler and more efficiently you can execute any of the skills, the more time and space you afford yourself on the ball. The more skills you master the more options you possess in the game. This makes you unpredictable and allows you to pose more complex problems to your opponent. Being able to execute the appropriate skill, as simply and quickly as possible, in as tight a space as possible is often the difference between success and failure.

Hurling is a team sport, but the team is made up of individuals. We train collectively, but will never reach our potential if we are not willing to practice individually. The players who commit to extra individualised practice are the ones you want on your team. The game needs time and if you want to maximise your potential you must be willing to give it time.

I was born and raised above my parents’ public house in Ballyhale. You could say it was a strange place for an athlete to be raised but for me it was perfect. There was a squash court behind the pub and this is where I honed my skills as a youngster. In the winter months I would be inside the court with the lights on and in the summer I would be outside on its gable wall. The challenge was always to try and hit the bullseye targets my brothers had painted on the wall. This required focus and concentration. If I missed, the challenge was to figure out why. For me, there was nothing like honing my skills- it drove my love for the game. All I needed was a wall, a ball and a hurl and I was happy.

As a youngster I practiced a lot with my brother Paul who was just a year younger than me. We were very competitive and we would challenge each other, keeping scores and always looking for a winner. Wanting to be the best was something that always drove me on. This period of my life undoubtedly laid the foundations for the hurler I would become. My skills were developed, my wrists and the hands were hardened and strengthened.

Throughout my underage club career we usually played in the B and C grades of the competitions. I didn’t really appreciate it at the time but this afforded me more time and space on the ball as the pace of the game was relatively slow. When I moved to secondary school in St Kieran’s College there was a huge change in game-speed and a sharp rise in standard. This forced me to look at all areas of my play and improve my hand speed and indeed foot speed. Focused practice was given to both areas away from collective training. Counsel and feedback was sought from coaches and wise heads.

As I matured and joined the Kilkenny senior panel I became increasingly aware of the areas of my game that needed more targeted work. The higher the level, the greater the chance of any limitation in my game being exposed. My left side needed strengthening. I was too predictable in possession with my left side only a very distant second option to my right. I went after improvement with relentless practice on my left side. The more I practiced the more confident I became on it. I was no longer predictable. I had multiple options in possession.

I always loved going down to the pitch by myself. I felt connected to it. It felt like home. I had picked the stones out of it when it was a farmer’s field and as a community we had brought it to life as a hurling field. It was a place that brought me to life. It was a place I was free with myself. For shooting practice I would bring twelve balls and scatter them randomly around the field. I would approach each ball individually with a 5 or 10 meter full speed run up, jab lift and then execute the shot. I used visualisation to make it as real or game-like as possible. Often, I would visualise the Cork half back Sean Óg Ó hAilpín breathing down my neck as I attacked the ball and took on the shot. I would count how many went over and as I walked in to gather the balls I would reflect on why I had pulled a ball on the near post or whatever. I was always asking ‘why’, always wanting to be better and always willing to do what it took.

When I joined the Kilkenny senior hurling panel DJ Carey was the team free- taker. At that time DJ was a hurling god. He helped me greatly not only in the area of free-taking but also in giving me an example of what a good teammate was and how you could influence and help those around you. We would practice together and he would offer me guidance and feedback.

My individual free-taking practice would go hand in hand with my individual shooting practice in the pitch in Ballyhale. In my early twenties, it would be over an hour down the field by myself on the evenings we weren’t training. I genuinely loved it. It was here I honed my routine; place the ball correctly on a nice piece of grass with the rim of the ball pointing in the direction of the target. Set my feet shoulder - width apart about a foot back from the ball with the ball placed centrally between them. Take two deep breaths, check that my shoulder and hurl are in line with the target. Chin down, jab lift and follow through. Each free was given focused attention and none were taken lightly; the routine I developed and practiced ensured this. Again visualisation played a critical role. Although I was standing alone in a field in Kilkenny in my mind I was in packed Croke Park and the pressure was on.

In the later part of my career I began to work one-to-one with Bro. Damien Brennan. He was a unique and great man and became a mentor to me. We would discuss areas for improvement in my game and often practice things one-on-one where he would give me specific individualised feedback. The idea was to find an area for improvement, discuss it and practice it with targeted and focused practice. I found working with him extremely beneficial and would recommend seeking the guidance of a mentor to anyone who wishes to keep pushing the envelope on performance.

I loved collective training. I loved being with the lads, on the training pitch, giving it my all. I loved the energy of it. I also loved practicing by myself. It was a habit I created as a child in the squash court and one that continued to develop and evolved as I met new challenges and learned more about myself as a player and the demands of the game I loved. My advice to any youngster who wishes to both enjoy their chosen sport and reach their potential in it would be to commit to practicing away from the crowds in places where no one is watching. Know your strengths but be willing to attack your weaknesses. Practice with purpose. Hone your craft and have fun along the way.

I wish you well,

Henry Shefflin

I played hurling. The technical demands of the game are huge. The simpler and more efficiently you can execute any of the skills, the more time and space you afford yourself on the ball. The more skills you master the more options you possess in the game. This makes you unpredictable and allows you to pose more complex problems to your opponent. Being able to execute the appropriate skill, as simply and quickly as possible, in as tight a space as possible is often the difference between success and failure.

Hurling is a team sport, but the team is made up of individuals. We train collectively, but will never reach our potential if we are not willing to practice individually. The players who commit to extra individualised practice are the ones you want on your team. The game needs time and if you want to maximise your potential you must be willing to give it time.

I was born and raised above my parents’ public house in Ballyhale. You could say it was a strange place for an athlete to be raised but for me it was perfect. There was a squash court behind the pub and this is where I honed my skills as a youngster. In the winter months I would be inside the court with the lights on and in the summer I would be outside on its gable wall. The challenge was always to try and hit the bullseye targets my brothers had painted on the wall. This required focus and concentration. If I missed, the challenge was to figure out why. For me, there was nothing like honing my skills- it drove my love for the game. All I needed was a wall, a ball and a hurl and I was happy.

As a youngster I practiced a lot with my brother Paul who was just a year younger than me. We were very competitive and we would challenge each other, keeping scores and always looking for a winner. Wanting to be the best was something that always drove me on. This period of my life undoubtedly laid the foundations for the hurler I would become. My skills were developed, my wrists and the hands were hardened and strengthened.

Throughout my underage club career we usually played in the B and C grades of the competitions. I didn’t really appreciate it at the time but this afforded me more time and space on the ball as the pace of the game was relatively slow. When I moved to secondary school in St Kieran’s College there was a huge change in game-speed and a sharp rise in standard. This forced me to look at all areas of my play and improve my hand speed and indeed foot speed. Focused practice was given to both areas away from collective training. Counsel and feedback was sought from coaches and wise heads.

As I matured and joined the Kilkenny senior panel I became increasingly aware of the areas of my game that needed more targeted work. The higher the level, the greater the chance of any limitation in my game being exposed. My left side needed strengthening. I was too predictable in possession with my left side only a very distant second option to my right. I went after improvement with relentless practice on my left side. The more I practiced the more confident I became on it. I was no longer predictable. I had multiple options in possession.

I always loved going down to the pitch by myself. I felt connected to it. It felt like home. I had picked the stones out of it when it was a farmer’s field and as a community we had brought it to life as a hurling field. It was a place that brought me to life. It was a place I was free with myself. For shooting practice I would bring twelve balls and scatter them randomly around the field. I would approach each ball individually with a 5 or 10 meter full speed run up, jab lift and then execute the shot. I used visualisation to make it as real or game-like as possible. Often, I would visualise the Cork half back Sean Óg Ó hAilpín breathing down my neck as I attacked the ball and took on the shot. I would count how many went over and as I walked in to gather the balls I would reflect on why I had pulled a ball on the near post or whatever. I was always asking ‘why’, always wanting to be better and always willing to do what it took.

When I joined the Kilkenny senior hurling panel DJ Carey was the team free- taker. At that time DJ was a hurling god. He helped me greatly not only in the area of free-taking but also in giving me an example of what a good teammate was and how you could influence and help those around you. We would practice together and he would offer me guidance and feedback.

My individual free-taking practice would go hand in hand with my individual shooting practice in the pitch in Ballyhale. In my early twenties, it would be over an hour down the field by myself on the evenings we weren’t training. I genuinely loved it. It was here I honed my routine; place the ball correctly on a nice piece of grass with the rim of the ball pointing in the direction of the target. Set my feet shoulder - width apart about a foot back from the ball with the ball placed centrally between them. Take two deep breaths, check that my shoulder and hurl are in line with the target. Chin down, jab lift and follow through. Each free was given focused attention and none were taken lightly; the routine I developed and practiced ensured this. Again visualisation played a critical role. Although I was standing alone in a field in Kilkenny in my mind I was in packed Croke Park and the pressure was on.

In the later part of my career I began to work one-to-one with Bro. Damien Brennan. He was a unique and great man and became a mentor to me. We would discuss areas for improvement in my game and often practice things one-on-one where he would give me specific individualised feedback. The idea was to find an area for improvement, discuss it and practice it with targeted and focused practice. I found working with him extremely beneficial and would recommend seeking the guidance of a mentor to anyone who wishes to keep pushing the envelope on performance.

I loved collective training. I loved being with the lads, on the training pitch, giving it my all. I loved the energy of it. I also loved practicing by myself. It was a habit I created as a child in the squash court and one that continued to develop and evolved as I met new challenges and learned more about myself as a player and the demands of the game I loved. My advice to any youngster who wishes to both enjoy their chosen sport and reach their potential in it would be to commit to practicing away from the crowds in places where no one is watching. Know your strengths but be willing to attack your weaknesses. Practice with purpose. Hone your craft and have fun along the way.

I wish you well,

Henry Shefflin