In the end, the scoreline of 2-14 to 0-11 in favour of Mayo read more or less as most people would have expected. However what most Mayo people coming out of McHale Park will remember is they were only a goal to the good with just a few minutes remaining against a Division Three side.

However, from where I was standing, even at a mere goal up with five minutes remaining, they did what good sides do to sides like Sligo. They did enough, more or less keeping them at arm’s length throughout.

There are a couple of key points to note when assessing why they didn’t wipe the floor with Sligo, and why, broadly speaking, it shouldn’t be of much concern to the Green and Red.

Firstly, Elverys McHale Park is a narrow pitch – 82 metres wide compared to 88 metres in Croke Park. Secondly, if you weren’t in McHale Park you wouldn’t have appreciated just how horrible a wind there was, going almost directly down the field.

When you combine those two factors and factor in how Sligo typically got 13 men behind the ball, it would be unrealistic to have expected a high-scoring massacre.

Sligo’s defence brings us to the first of four significant points in the game.

Sligo’s Defence

Sligo didn’t just get numbers behind the ball. The manner in which they did so ranked amongst the most methodical in the country.

They didn’t set up with a sitting sweeper as such, but number 10, Neil Ewing, actually lined out and played as a wing-back, and number five, Keelan Cawley, essentially played as a defensive midfielder “from the wing-forward position”. Set up like this, Sligo funnelled back extremely efficiently.

At various times, Ewing, Cawley, Brendan Egan at number six, Adrian McIntyre at number 9, and even, occasionally, Charlie Harrison from number 3, sat alone or as double or triple sweepers in front of the Mayo full-forward line.

It’s not rocket science to take up the most efficient position in such cases, but a frightening amount of top end players and teams get it chronically wrong. The positioning of Egan, Cawley and Ewing were spot on, almost throughout.

As you can see in the example below, Sligo didn’t leave much in the way of angles or space for ball to be played in front of Andy Moran and Co.

Sligo with three and four well-positioned surplus players

Particularly, shooting into a horrible wind, it would have been optimistic to have expected Mayo to have scored much more than they did in the first half.

The flip side of this is that Sligo were frequently too shy up front, with nobody within 40 yards of goal on at least three occasions as they broke forward, and typically, with no more than two throughout.

You don’t massacre a well-organised side like that. You grind them down. And that’s what Mayo did.

Breaching the Line in the Middle Third

Almost certainly the key element in the game were the respective attitudes and abilities in the middle third. Sligo’s default position seemed to be to play the ball laterally and slowly in that area.

Mayo, on the other hand, looked to constantly break the line at pace in that part of the field. The intriguing element was just how they managed it.

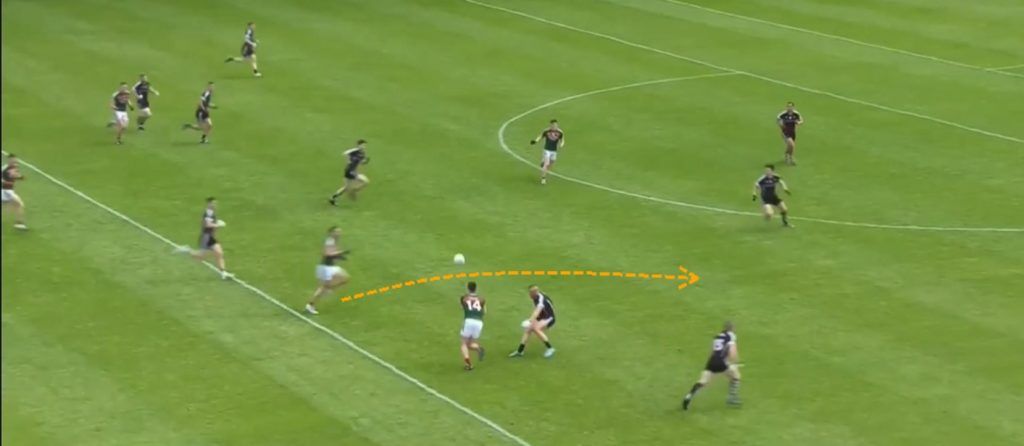

From 1-6 scored in the first half, four points came from a line break in the middle third (the central area extending five yards past each “45”) where there was one common, key feature. The line was broken by a player coming off the shoulder of a hand-passer, who made that hand-pass within two seconds of having possession, before even hopping or soloing the ball!

They broke the line for their first goal in a similar manner, the hand-pass given within two and a half seconds after one hop, and a fifth point in the aforementioned manner in the final third of the field.

Mayo break the line for a score with a quick hand-pass

Playing more directly in the second half, wind assisted, they would get a more modest, but still significant 0-3 from 1-9 like this.

In the entire game, Sligo scored just a single point where they made a line break in this fashion in the middle third.

This is possibly the central element in Mayo’s game-plan. It will be worthy of more analysis, as Sligo didn’t appear to think two steps ahead and step off the runner, in situations where they could have.

Without having analysed this element previously, one wonders if certain oppositions choking off this source could account for Mayo’s somewhat schizophrenic results in the last year.

Could you expect them to struggle hugely if a side stepped off the runners in advance and choked off this source that accounted for a key line break in between 0-7 and 1-8, from 2-14, depending on how rigidly you calculate?

Assuming Mayo reach Croke Park in July, they’re going to finish out their season playing on a much wider pitch and it’s unlikely they’ll play in such windy conditions and, against Kerry or Dublin at least, it’s unlikely they’ll play against a side who get so many men behind the ball systematically. Even if they did, it’s not possible that they’ll have to break down such a defender-to-space ratio in Croke Park.

So what can we take from Sunday in terms of going forward as All-Ireland contenders?

Kick-outs

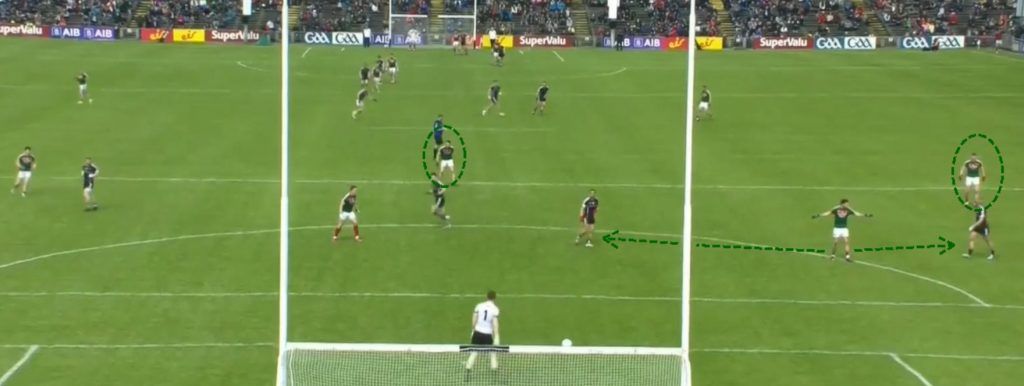

Interestingly, as opposed to trying to go man on man on the kick-outs, as they did last September/October against Dublin, they split Sligo’s full-back line, and allowed one player to drop, typically between the full-forward and half-forward line.

Again, on the narrow pitch, splitting the opposition full back line is more viable as they have significantly less space to manoeuvre. Considering how key it has been to prevent Dublin from getting off the quick, short kick-out has been in their four championship games over the last two years, it was interesting to note.

Mayo split the full-back line, allowing two players to cover the space and get under the breaks

Perhaps, this policy was based on the narrower field and windy conditions. Had they pushed up man on man, it would have been too easy for Sligo to send the kick-out over the top and find a man-on-man forward line. All in all, it probably made sense.

More significantly, Mayo scored 2-2 directly from winning long Sligo kick-outs, while only conceding 0-4 from the same source.

On one hand, it illustrates how superior they were, man on man, compared to Sligo, as this source represented the rare occasions where they found themselves not attacking into a blanket defence. It also illustrates how ruthless they can be when they counter or make ground quickly after winning the kick-out.

On the other hand, it left you asking what might have been if Sligo had worked out something a bit more efficient, such that they could have replicated their packed defence quickly upon losing the kick-out.

A cynic might suggest systematically fouling and obstructing and delaying the free taker, if they wouldn’t have been carded for such offences.

Soft Score Concession

On the basis that Mayo haven’t beaten Dublin in 11 attempts under Jim Gavin and haven’t beaten Kerry in Championship football since 1996, I think it’s probably fair to say that they are inferior to both in terms of raw ability.

In such circumstances, you must find an edge, some sort of angle, that you can create a margin of a couple more points somewhere, if they’re to expect to beat either of these.

When Tyrone won All-Irelands under Mickey Harte (and still now) and Donegal won in 2012 and beat Dublin in 2014, they had one thing in common. They conceded an absolute minimum of soft scores and unnecessary frees.

I’m more than just a bit of a groaner when it comes to the amount of scores conceded, even at the top level of Gaelic football, where the attacking team didn’t have to take on and beat a defender in order to score.

Except for the Hartes and McGuinnesses of this world, most of the top sides concede far too many of these for my liking. Whether it’s players kicking points outside “blanket defences” without being closed down, attackers drifting behind defensive lines untracked, or forwards who pose no direct threat, like when their back is to goal with spare defenders behind them, being fouled, even most of the top sides concede too many. Harte’s and McGuinness’s All-Ireland winners didn’t.

When I analysed last year’s drawn All-Ireland final, I found that Mayo had conceded 1-4 in such soft scores, and Dublin 0-6. That incidentally, didn’t include Colm Boyle’s own goal, which was a freak, but did include Kevin McLoughlin’s as it came from Brian Fenton going one-on-one after Séamus O’Shea never tracked a simple, one-dimensional run from Fenton.

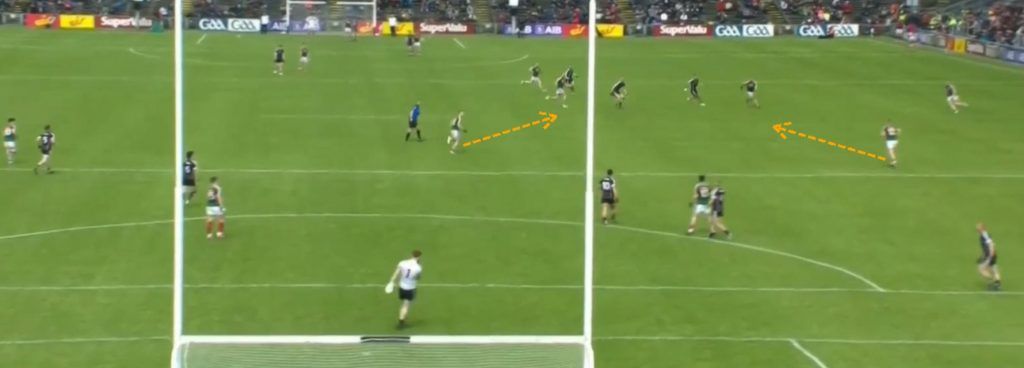

Against Sligo, Mayo conceded five frees that were completely unnecessary and allowed three more points to be kicked over without a defender needing to be taken on and beaten, totalling 0-8 in soft score concessions.

Mayo concede completely unnecessary frees

Had Sligo’s kicking been as clinical as you’d expect Dublin’s or Kerry’s to be, even on a windy day, it would have been significantly more.

If Mayo are to close the small gap to Dublin and Kerry, and gain that extra something, cutting these scores to Harte or McGuinness levels is where it’s at. In that regard, they’re still a good way off.