Galway fully deserved their victory against Mayo, but coming into this game there were three reasons why their huge favourites tag wasn’t justified.

Firstly, they beat a 15-man Mayo last year and still went out in the quarter-finals to Tipperary.

Secondly, Kevin McStay had to completely reshuffle his panel this year. You don’t manufacture a unit with so many new faces in such a short amount of time like the league allows – negative analysis of their league campaign seemed to miss this point.

Thirdly, and most significantly, Kevin McStay is one of the top football thinkers in the country. Lest we forget, he was the only one (I can remember) who predicted that Kerry would beat Dublin in 2009!

He’s as meticulous and theoretically sound a football planner as there is, and make no mistake about it – this victory was the result of a meticulously-executed plan.

Zonal Defence Analysis

When the game is broken down into different types of attacks we’ll find that, within broad parameters, there wasn’t a huge difference between the sides in terms of raw ability.

When facing into blanket defences, Roscommon had a 28 percent attack-to-point ratio throughout while Galway had a 24 percent ratio. Both are considerably lower than average, but then the conditions have to be taken into account.

In terms of man-on-man attacks, Galway had a 100 percent attack to point ratio while Roscommon had an 85 percent ratio.

Each side created three attacks off turnovers high up the field. Galway scored one from three while Roscommon scored two from three.

The key, of course, was the respective amounts of different types of attacks created by each side. While Roscommon managed more attacks by 45 to 39, the key element is that they manoeuvred 13 man-on-man attacks while Galway’s only managed three.

From Galway’s three man-on-man attacks they scored three points. From Roscommon’s 13 they scored 2-5. Winning by 2-3, this aggregate 2-2 was ultimately the difference between the sides.

How did Roscommon manoeuvre so many man-on-man attacks?

While creating man-on-man attacks can partially allude to the raw ability in defence and midfield to take on and beat the opposition or to take out the middle third with killer passes, typically it has more to do with tactical application.

What is particularly noteworthy is that while two of Galway’s three man-on-man attacks came off the back of winning long kick-outs, Roscommon’s were split almost evenly. Six came off the back of winning long kick-outs while seven were manoeuvred from the back or from midfield from open play.

From these seven a killer pass took out the Galway middle-third on three, two came from carrying the ball at pace/off the shoulder on counter-attacks and two came directly from throw-ins.

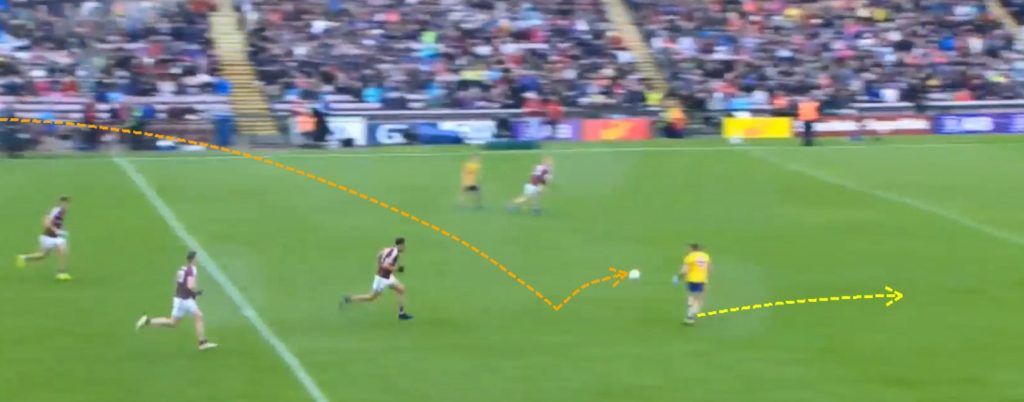

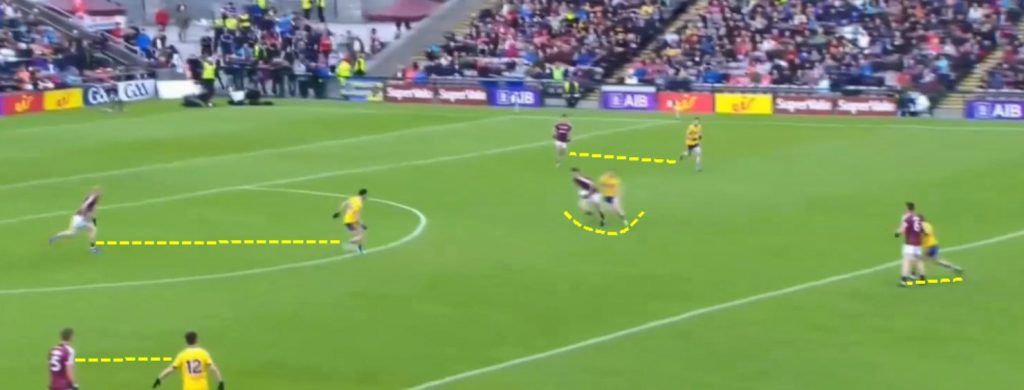

Galway have four men behind the ball and two more free out of picture

But one pass takes out the entire middle third

With both sides going man on man on kick-outs, the key question is how did Roscommon prevent Galway from creating so few man-on-man attacks?

Firstly, they systematically and intelligently fouled and delayed Galway’s taking of frees all afternoon.

The foul was whistled with 12.40 on the clock

But the Roscommon’s Tadhg O’Rourke is still in contact with the Galway man at 12.44

Allowing four Roscommon men get behind the ball

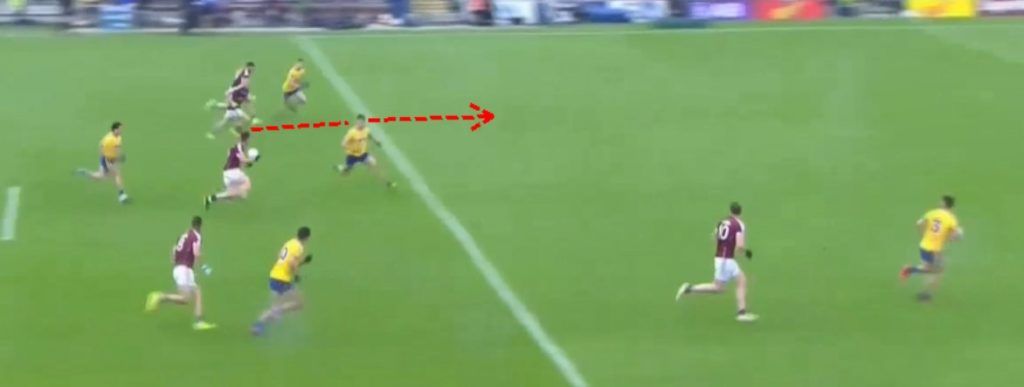

It was a constant theme throughout and was clearly meticulously planned and executed by Roscommon, as the following sequence of images again illustrates, with Galway’s Gareth Bradshaw set to potentially create an overlap.

Gareth Bradshaw has the overlap to his left

But Seán Mullooly makes sure to foul him. The clock reads 22.18

Three seconds after the whistle, with the clock at 22.21, Mullooly is still holding on

Allowing Roscommon men behind the ball again

When Croke Park eventually catch up and apply serious penalties for this obstruction after a free is awarded, it will completely change football. For now, it creates advantages for clever managers and players. Roscommon applied this tactic ruthlessly.

The second area which allowed Roscommon create such a high proportion of man-on-man attacks relative to Galway, was kick-outs.

Galway’s kick-outs

Tied in with the previous figures, to some extent, is the fact that the foundation for Roscommon’s victory was laid with the most military-like, systematic success on kick-outs.

Counting both raw scores and also counting the first side to have clear possession on kick-outs, Galway actually came in at a higher win/loss ratio than Roscommon. These one-dimensional figures, however, would paint a disfigured picture.

If we exclude figures from the 69th minute when it suited Roscommon tactically to allow Galway to have short kick-outs, throughout the rest of the evening, Galway got off a mere five short kick-outs. None of them were taken quickly. Roscommon turned them over immediately and scored points from two.

In total Galway scored just one point from nine short kick-outs while conceding four on the initial turn-over, a 0.33 point-per-kick loss. Many sides try to apply man-on-man pressure on the opposition’s kick-out, but typically, forwards give themselves away by not understanding even basic elements of man-marking or preventing opposition defenders from making the run to the space.

Roscommon were clearly schooled enough in this regard to ensure that it would be extremely difficult for Galway to get the short kicks off, and that if they did, that they’d have Roscommon men hot on their heels.

This is despite the fact that Galway had clearly worked on trying to create runners for the short kick-out.

Roscommon are tight, man-on-man

Forcing a tight kick-out to a marked man

Who is under pressure immediately

And the turnover is forced for a Roscommon point

Galway’s cause wasn’t helped by some small details. In the following image, you’ll see that the spare ball isn’t even at the post. It delays the kick by a crucial two seconds.

And when it is lined up, Ruairí Lavelle’s angle is straight behind the ball. This reduces the arch of the angle which he can hit, so he can’t pick out number 12, Johhny Heaney, who has peeled off his man.

He should be at a 30 to 40-degree angle which would give him the whole scope of the field where he could actually hit the free man who is in a safe amount of space.

Early in the second half, Galway didn’t even have a spare ball on the post. It takes Lavelle 15 seconds to get the ball on the tee after fetching it.

By contrast, Roscommon got off four quick kick-outs and scored 1-1 off them.

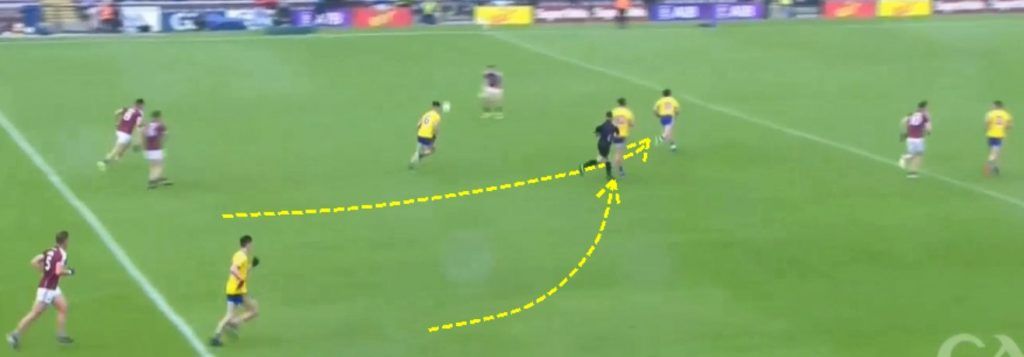

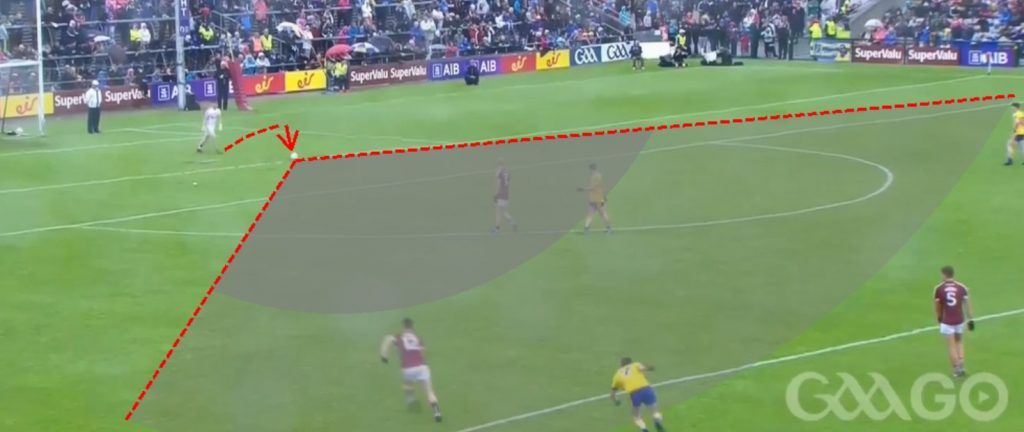

This is 15 seconds after Galway kicked a point, allowing for the quick break

Which saw one quick ball lead to this man-on-man attack which Roscommon netted

Interestingly, from the kicks where Galway went long, they won nine and lost 11, but managed to score four points. However, they conceded 1-2.

What is interesting is that from these 20 kick-outs, four appeared to be specifically directed at a particular Galway player with a low trajectory strike. They lost three of these and won one on the break. They conceded a goal off one of these!

For all of Galway’s meticulous planning on kick-outs, in the heel of the hunt from the 16 where they went long and hard, they won eight and lost eight, scoring four points and conceding two.

By those figures, had they gone long and hard on all kick-outs, you could have expected them to have fared 1-3 better off.

Roscommon’s kick-outs

By comparison, Roscommon’s kick-outs were executed with military precision, in the first half at least. They were only forced to go long four times in the first half, and didn’t lose any of their own kick-outs until the 32nd minute. They had gone short on four and won two long ones. It was good foundation for only having conceded two points at this stage, leading 1-7 to 0-2 on 32 minutes.

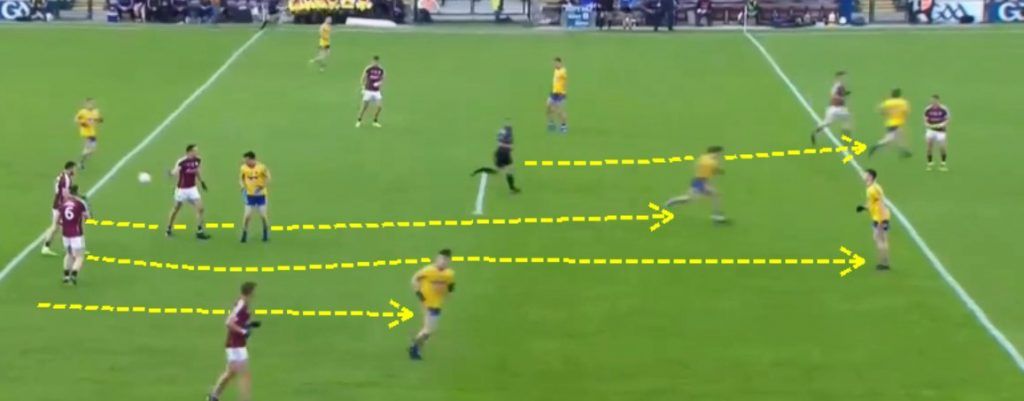

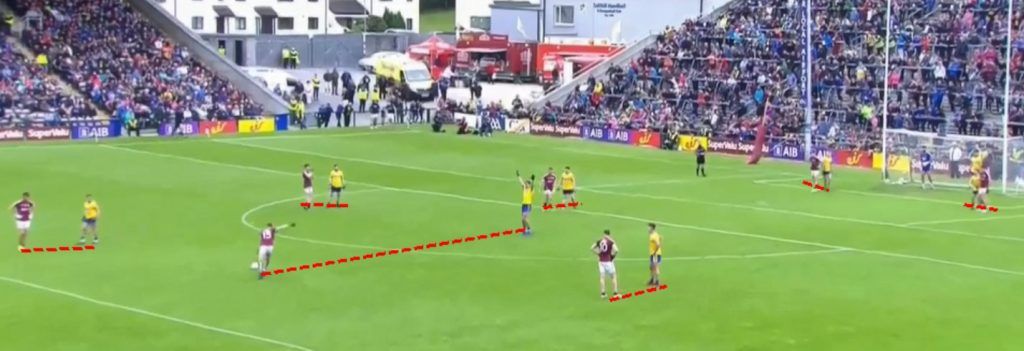

Galway are perfectly set up to go man-on-man after the free is kicked

And are clearly planning to

But the man-marking is far too lax

And Roscommon gain easy possession

In fact, it was when Galway re-shaped on the Roscommon kick-out in the second half and forced them to go long that they launched a comeback. They won four long Roscommon kick-outs in a row and turned all four into points.

However, Roscommon got two of the next four off to the half-back line and won the next two long. In total, Roscommon won five and lost seven of their long kick-outs, and scored two points while conceding four, a 0.17 point per kick net loss.

From seven kick-outs to the full or half-back line Roscommon scored three points and conceded one upon the first turnover, a 0.28 point per kick net gain.

By those figures, if Galway could have pressed high efficiently on all kick-outs, as was frequently done to them, and forced Roscommon long on all kick-outs, you could have expected them to have grossed two points less conceded on short Roscommon kick-outs and grossed three or four points more scored on long ones.

Free Concession

A further failing on Galway’s part, compared to their victory against Mayo was that they conceded four scored frees where no direct threat existed or fouled a player as he shot wide. Against Mayo they conceded just one such score. Granted, David Gough’s eagle eyes accounted for two of these, ahead of the ball, something which may or may not have been going on in their Connacht semi-final victory.

One flaw in Roscommon’s performance was that they were also guilty of conceding four such frees. It’s difficult to imagine that they have the raw ability of Dublin or Kerry, who could afford to give away such frees and still potentially win an All-Ireland.

To that end, if there’s even a reasonable outside chance that they could topple one of these big guns, on top of an equally efficient tactical performance, they’ll need to completely eliminate these unnecessary scoreable frees.

For Galway, it remains to be seen if they can reach the dizzy heights of their slaying of Mayo a second time this season as they face Donegal.

Stephen O’Meara is the creator and owner of www.gaaprostats.com, statistical and video analysis software designed specifically for Gaelic football and hurling.