Based on figures from Kerry’s two league games against Dublin this year, coming into the Championship, I put them at almost 50/50 with Jim Gavin’s side. Only one thing I saw from their victory against Cork would have made me think significantly differently.

Let’s start by looking at the basis of how they lost to Dublin last year, how the league illustrated that they appeared to have remedied these issues, and how it all tied in with their Munster Final victory against Cork.

2016 All-Ireland SFC semi-final

Two statistical patterns stood out that day which, had they been spotted at the time, could have made Kerry likely winners.

On the day, Kerry kicked 12 short kick-outs. Only two were hit quickly (typically far more likely to result in a score). They racked up an off-the-charts five points from 10 short kick-outs, not played quickly, and one from two on the quick ones, totaling a 0.5 point profit per kick on both counts. They conceded nothing upon the first turnover from the other six.

It encapsulated all that is Kerry – the ability to create a score from box to box against a 15-man defence.

In the league final this year, they scored four from four, 100 percent, where they gained possession off a short kick-out.

The key problem for Kerry last August against Dublin was that from 18 of their own long kick-outs, they only won six and lost 12. They scored nothing from the six they won and conceded six points from the 12 they lost. They lost the majority on breaks.

In short, they made 0.5 of a point net profit per short kick-out and a 0.33 of a point net loss on long ones. The difference on “Expected Value” between the decision/ability to go long or go short was a breathtaking 0.83 of a point per kick.

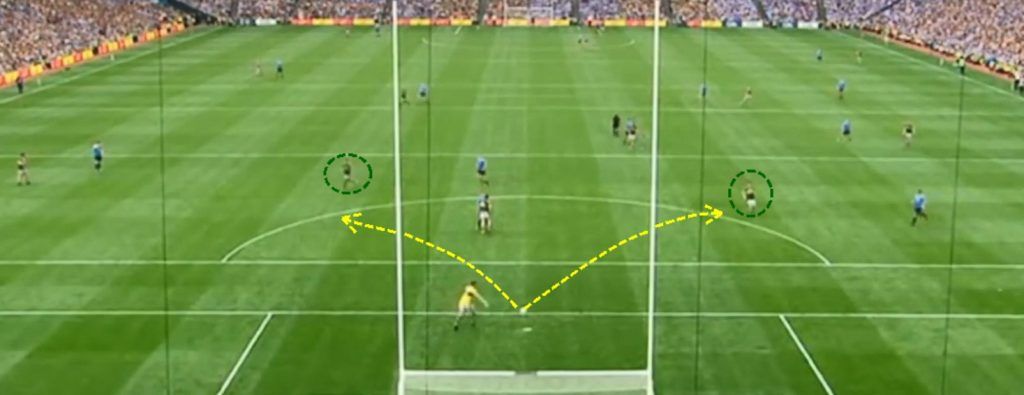

Yet, even late in the game with this pattern well-established, a point up, Brendan Kiely overlooked an easy attempt at a short kick-out to a choice of two players, and went long. Predictably, Dublin won it on the break and equalised.

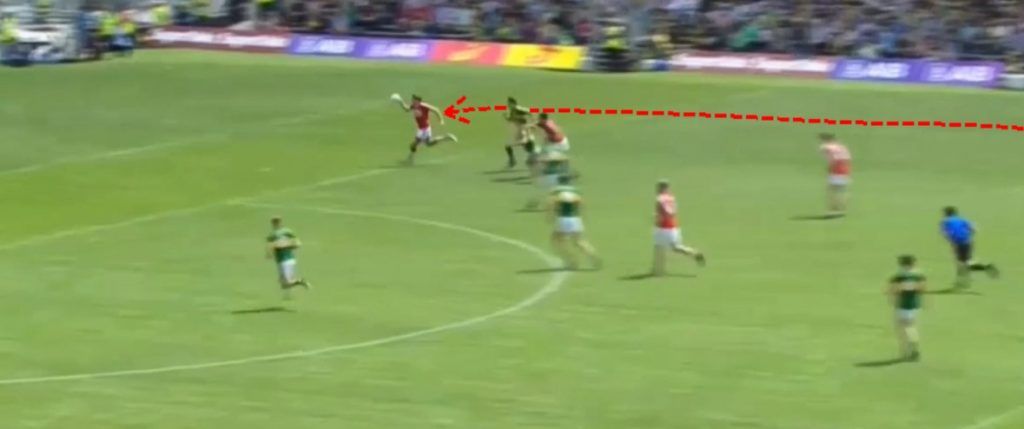

Kiely had two free men to hit

But sent it long where Kerry lost it and conceded

Conclusion for 2017?

- Kerry must prioritise getting off short kick-outs at all costs, because they can concede heavily on their own long kicks and they have the capacity to make a serious profit from short ones, even against the best of opposition.

- Kerry must to be more efficient under breaks off their own kick-outs to avoid the potential of being routed from this source like last year against Dublin.

- Kerry need a keeper who can spot the free man, and more importantly, hit him with a kick-out in a tight space.

In the league final this year, however, they won 13 and lost only eight of their own long kick-outs. Significantly, they only lost six breaks to five from their own kick-outs. It had clearly been worked on.

Let’s have a look at how they fared against Cork on these, and other elements

Zonal Kick-out Analysis

Kerry have clearly come to recognise the value in getting off the short kick-out. It appeared to be option Number 1 on all occasions. While they only tried eight from 24, reaching their target successfully on seven, you have to bear in mind that Cork didn’t apply a sweeper and were basically man-on-man for Kerry’s kick-outs. To that end, seven was quite impressive.

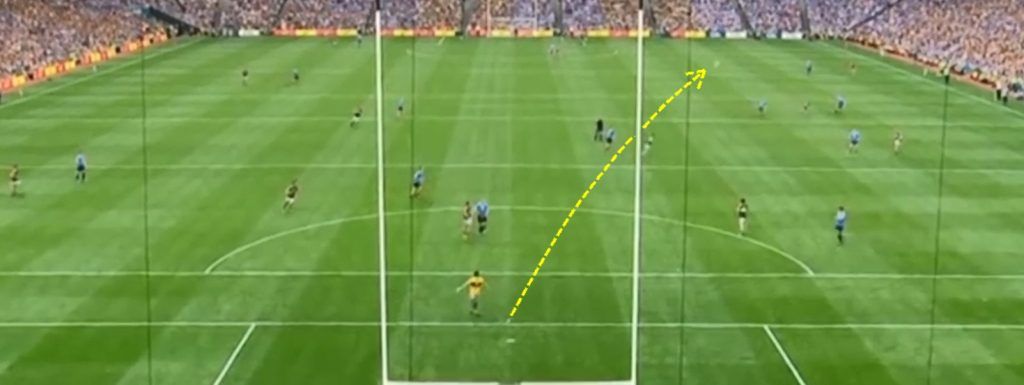

Noteworthy, compared to the previous image from last year against Dublin, it was clear that Brian Kelly was trying to hit free defenders and midfielders, even where only very small gaps appeared. Further, it appears as though he has the ability to do it. This will be key for Kerry.

Maher only had half a yard on his man

But Kelly dropped it on his nose, effortlessly

From these seven kick-outs to the full or half back line, only one was kicked inside the statistically significant 9.5 seconds. In total from these seven kick-outs, Kerry scored an impressive three points. However, they conceded two upon the first turnover, so their net figure from the eight was 0-3 to 0-2, or 12.5 percent of a point profit per short kick-out.

They won seven of their own long kick-outs and lost six. Significantly, in keeping with the low figure from the Dublin game last year, but not the league final this year, they only scored one point from the seven they won, while conceding two from the six they lost.

Though less blatant than the figures from the Dublin game last year, there is still an obvious pattern. Kerry are doing far better from their short kick-outs than their long ones.

As only three Kerry kicks ended up being won/lost on breaks, with Cork winning two-to-one, this element remains to be seen.

Cork’s Kick-outs

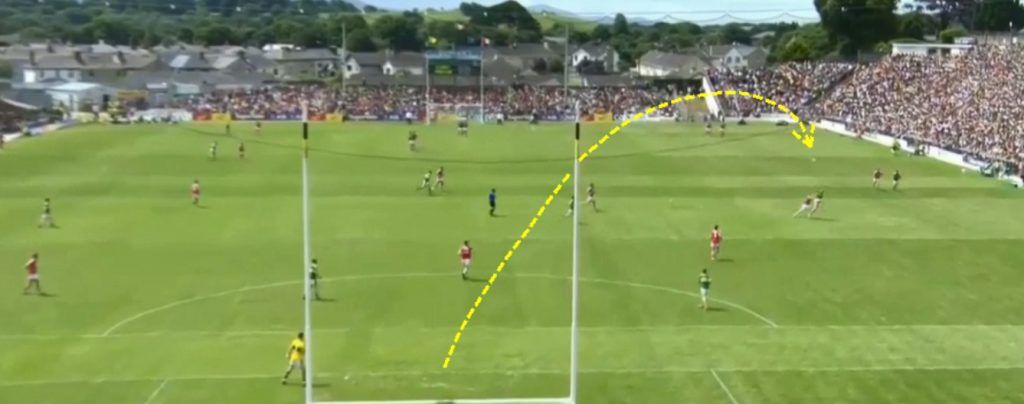

Where Kerry actually murdered Cork was on Cork’s long kick-outs. Kerry won 11 and lost nine, but scored a massive 1-6 off the 11 they won, conceding just 0-3 on the nine they lost. Two such scores at the beginning of each half, after Kerry had scored straight off the throw-in, accounted for Kerry’s runaway start to both halves.

Interestingly, Cork drew even from their eight short kick-outs (none were quick) scoring two points and conceding two points upon the initial turnover, making a neutral read-out.

Obviously, the opportunity to go short wasn’t there on many others, but hypothetically, by those figures, had Cork managed to go short on the 20 kicks where they went long, you could have expected them to have finished the game 1-3 better off.

Considering the manner in which sides such as Sluightneil, the Ulster club champions, systematically manage to work short kick-out set-plays, even against sides hell-bent on preventing them, it’s food for thought for Cork.

Cork manoeuvred a point from this short kick

Going against the grain of typical averages, it seems both Kerry and Cork are best served by the short kick-out, even if they’re not taken quickly.

Zonal Defence Analysis

The most noteworthy element of “Zonal Defence Analysis” is that only 54 percent of all attacks were launched into out-and-out blanket defence. This is much lower than normal, alluding to how both sides went man-on-man on kick-outs with neither applying a sitting sweeper, as well as both sides’ efforts to attack quickly from the back.

That Kerry scored 1-11 from the 22 times they faced an all-out blanket defence, a 64 percent score ratio, is frighteningly high. Team averages tend to run below 40 percent.

James O’Donoghue

There is one stand-out number from the aforementioned Zonal Defence Analysis, relating to James O’Donoghue. In the first half, when Kerry played into the wind, from 20 attacks which faced a blanket defence or one spare defender, where the ball went through O’Donoghue’s hands, Kerry scored seven points from 13 attacks, a 54 percent ratio. On attacks that didn’t pass through his hands, they scored two from seven, a 28 percent ratio.

Had Paul Geaney converted his 27th minute goal chance, those figures would have read 1-7 from 13 and a 77 percent attack to score ratio when the ball passed through O’Donoghue’s hands while facing a zonal defence.

His raw ability as an attacker is clear for all to see. These figures, however, suggest a more subtle intelligence in setting up ideal attacking circumstances with the right pass, insignificant as it may appear to be.

O’Donoghue receives the ball facing a blanket defence

And feigns to go left

Before coming back right and drawing five defenders

Before popping it back to Maher who is now unmarked, to kick over

Kerry’s Flaws/Cork’s Strengths

Also interesting are the facts surrounding Cork’s attack to score ratio where Cork sent direct ball in compared to when they played through the phases without going long.

Those pertaining to be “purists”, stop reading now.

In the first half from 18 Cork attacks/attempts at attacks built from the back/midfield, which involved trying to play a pass more than 30 metres forward, they scored two points from 12 attacks, a 17 percent ratio. Kerry conceded a free on both occasions.

From attacks where they never tried to play such a pass and only played short “pick and poke” passes, they scored seven points from 10 attacks, a seventy percent ratio!

The reason for this appeared simple. While the basic theory of Cork trying to attack quickly with direct ball makes general sense, the problem was that they virtually always faced a Kerry sweeper when they attacked via a kick pass, and they simply didn’t have the collective raw ability to cope when outnumbered.

When they delayed the attack, they brought extra men in from behind the play, negated Kerry’s spare man, and attacked on more favourable – albeit it more crowded – terms.

By those figures, had Cork chosen “pick and poke” on every occasion in the first half, you could have expected them to have been five or six points better off at half time!

Kerry’s Issues

This obviously has implications for Cork’s strategy going forward. More significantly, in terms of who is going to win the All-Ireland, it raises an alarm bell for Kerry.

Considering how efficient Dublin have become at “pick and poke” football in the last three seasons, not to mention Tyrone this year, it’s a somewhat worrying pattern that Kerry would have conceded so many points when Cork “picked and poked” in the attack.

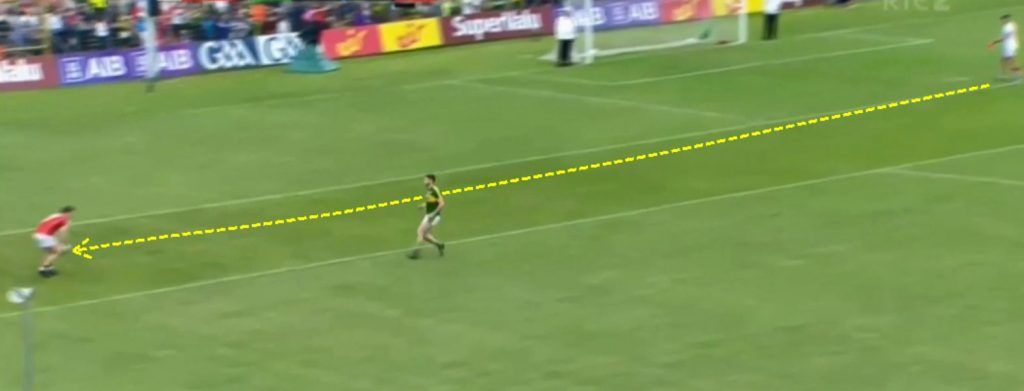

Firstly Maher is taken on and beaten too easily by O’Driscoll

Then all Kerry eyes are on Kerrigan

But nobody watched Maguire’s run, as he got in for the point

Equally alarming is that they conceded 10 scoreable frees. More alarmingly, seven were complete gifts, where the Cork man was running away from goal or into a spare defender. By contrast, Tyrone conceded one such free against Donegal!

Kerry foul a man who poses no threat

Conclusion

Patterns surrounding Kerry’s own kick-outs suggest that they’ve realised and have fixed that biggest stumbling block from last year.

To be 50/50 with Dublin, however, the two aforementioned defensive elements will have to improve.

As for Cork, they’re clearly not All-Ireland contenders. However, if they could create a set-play to consistently create the short kick-out and resist the temptation to play long passes towards defences with sitting sweepers, a semi-final wouldn’t be beyond reason.

Stephen O’Meara is the creator and owner of www.gaaprostats.com, statistical and video analysis software designed specifically for Gaelic football and hurling.