After analysing Mayo’s game against Sligo three weeks ago, I speculated that we may have uncovered the key to Mayo’s enigmatic performances over the last 12 months.

Sunday’s defeat to Galway confirms it. The explanation for Mayo’s schizophrenic results lies in the “One-Two-Three”.

Following the Sligo match, I pointed out that 1-7 of Mayo’s 2-14 against Sligo had come from what I call the “one-two-three” in the middle third.

The initial line-break that led to 0-7 of Mayo’s score tally came from a Mayo man (the third player) taking the ball at pace, off the shoulder of a man who had received it (the second player) from the first player, less than two seconds after the initial pass.

They scored a further goal from this source if we extended the two seconds to two and a half seconds, and another point if we counted “one-two-threes” in the final third, totalling 1-8 from 2-14.

On seven occasions against Dublin last weekend, Carlow tried the “one-two-three” line-break (up to the 47th minute red card), breaking the line six times and scoring/earning a scoreable free five times.

Therefore Mayo rely heavily on creating scores off the back of the “one-two-three”, which they are the masters of, and that Dublin are inept at defending it. When you pit these two sides against each other, we have a huge score concession pattern for Dublin against Mayo.

What, however, would happen if Mayo faced sides who don’t fall into the “one-two-three” trap? Could a side you’d expect Dublin to steamroll cause Mayo trouble?

Based on Sunday’s figures, the answer is an overwhelming “yes”.

From start to finish Mayo didn’t gain a single score from this source. Not only that, in the entire game, they didn’t break the line once off the back of the “one-two-three” where the two passes were hand-passes, and did so only once where the first pass was a kick-pass.

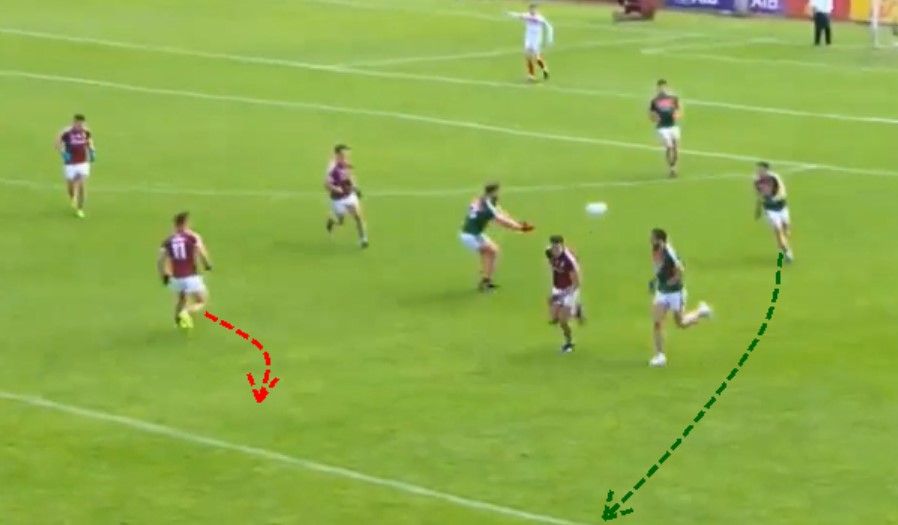

This pattern alluded to one of two exemplary elements of Galway’s defending. Unlike Dublin, Galway players have clearly been coached not to be drawn to the ball/second player in the “one-two-three” (the one who gives the line-breaking hand-pass to the line-breaking runner). It’s the defender being drawn to this player which creates the line-breaking opportunity.

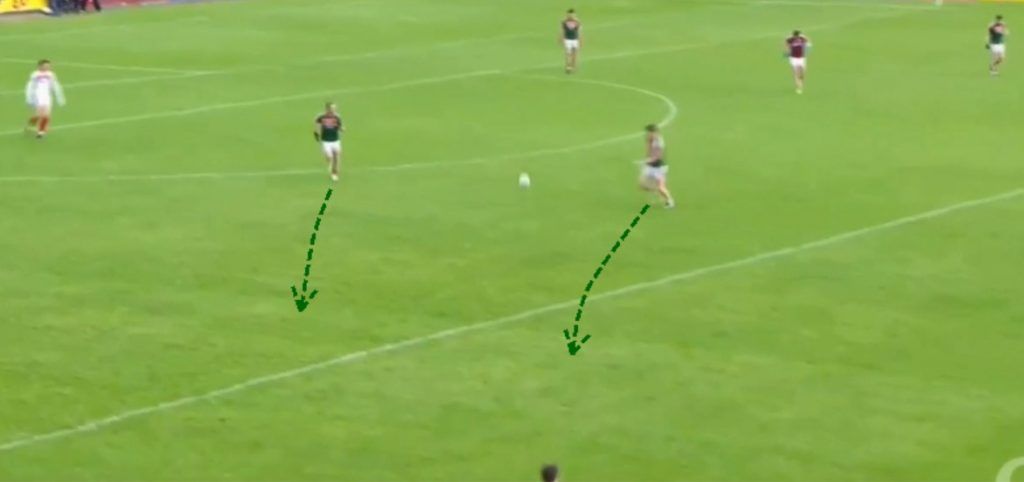

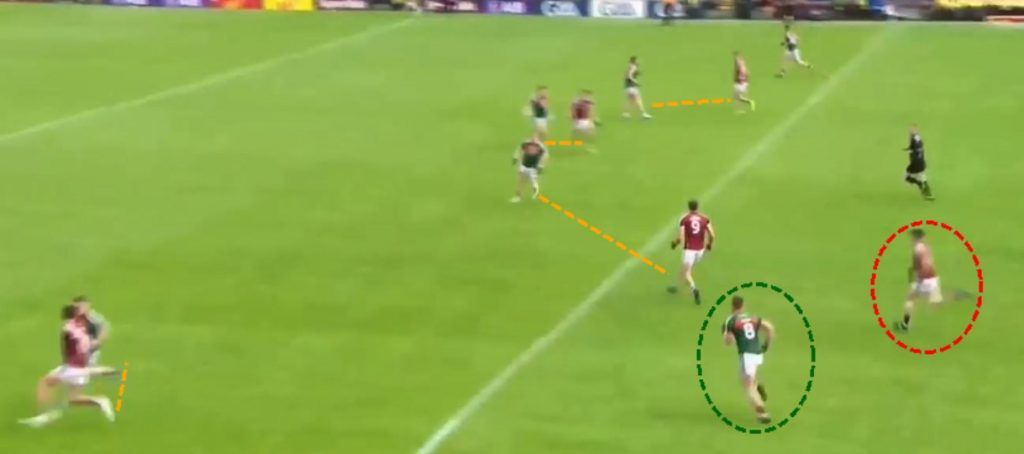

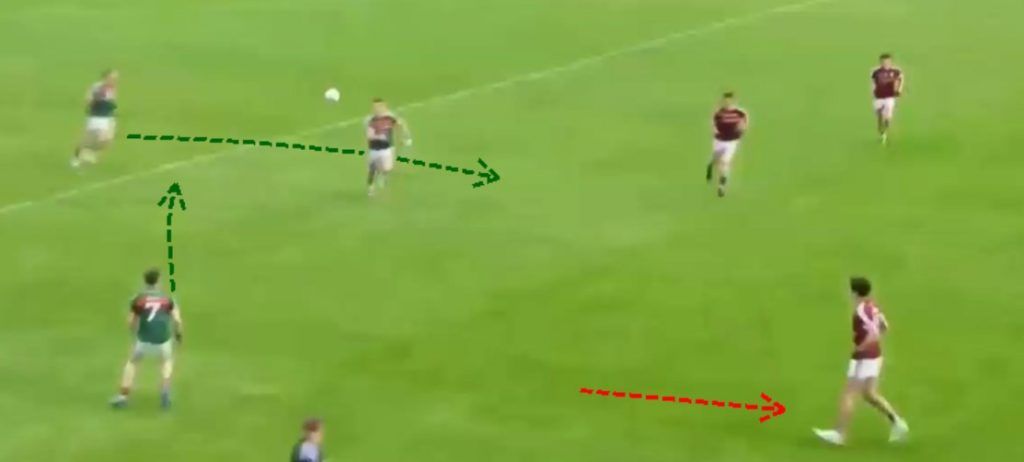

In the following sequence of images you’ll see that Mayo are perfectly set up to create their textbook “one-two-three”, but it’s no coincidence.

From the time Lee Keegan has picked up the ball, Keith Higgins, from a seemingly insignificant position, has sprinted behind him, ready to be the third player in the “one-two-three”.

If Galway’s Michael Daly falls hook, line and sinker for it, he’ll move towards Mayo’s Patrick Durcan and leave the gap for Higgins to break into. But he doesn’t. He backtracks and deprives Mayo the space.

And as we can see, instead of Mayo being set up to break the line off the shoulder with a textbook “one-two-three”, Galway are perfectly set up to defend zonally in a compact blanket defence.

You’ll see Galway’s Johnny Heaney points at the space and the runner to make sure all is in order. It has clearly been coached.

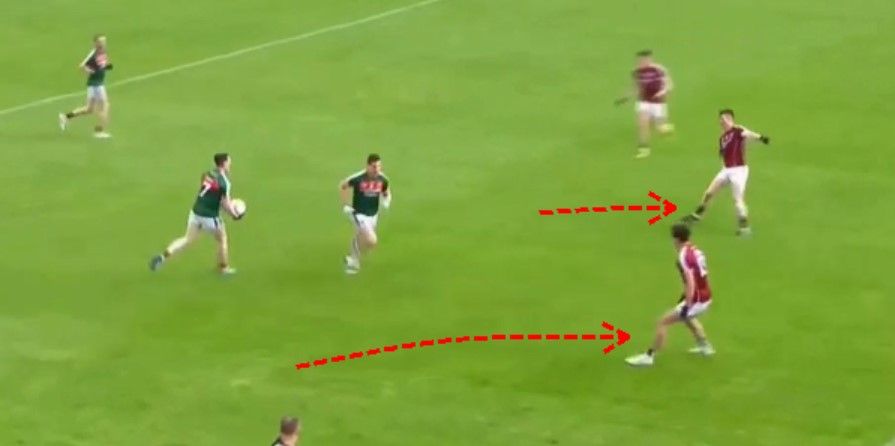

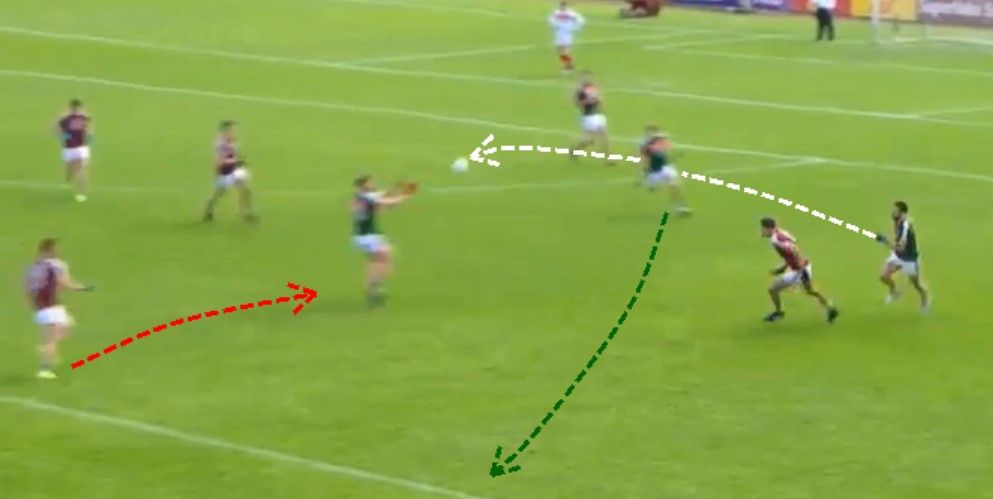

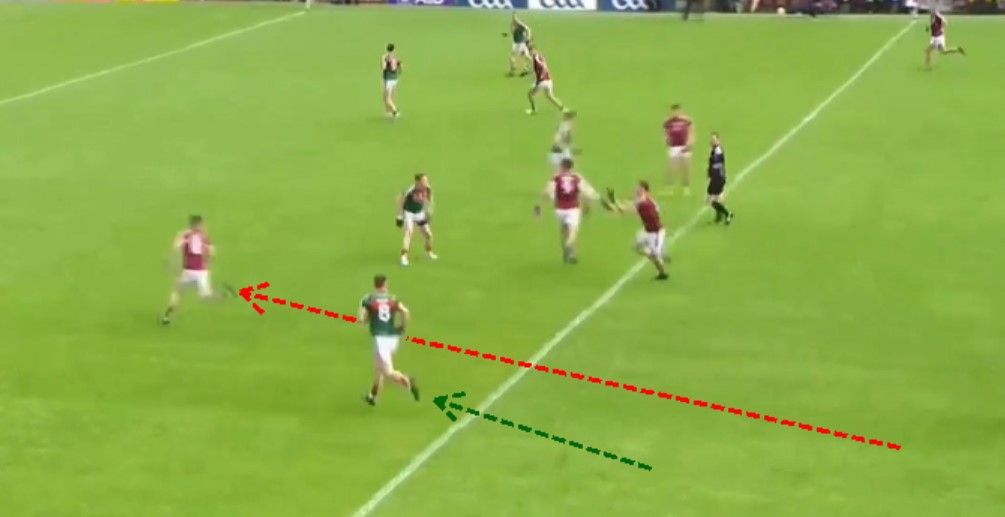

It’s the same again, later on, as Tom Parsons, Aidan O’Shea and Chris Barrett are in a textbook “one-two-three” formation” as they build from the back, with Barrett set up to break the line. This, however, would require Galway’s Paul Conroy to get sucked towards the ball.

Conroy is too shrewd, however. He shadows O’Shea, but doesn’t get too close and compromise his space covering position. So, when Barrett gets on the end of the “one-two-three”, Conroy is perfectly set up to track his run and prevent the line-break into swathes of space.

The conclusion is quite simple. Mayo losing to Galway last year probably had precious little to do with Mayo lads being in college, being caught cold, or any other such flippant explanations. Like this year, it probably had to do with Galway systematically choking off Mayo’s primary route to scores.

Yes, Mayo played with 14 men from the 25th minute, but they had failed to break the line off a “one-two-three” up to this point, and had a pointed attempt not come fortuitously off the post to set up their goal, they would have trailed by 0-7 to 0-3 or 0-4 at the time, albeit, playing into the wind.

Mayo’s Defence

Tomás Ó Sé stated on The Sunday Game that Mayo have the best numbers one to nine in the country. I couldn’t disagree more. From an attacking point of view? Maybe. From a defensive point of view? Forget about it.

Against Sligo, from nine points/scoreable frees concede, eight were categorised as the defensively criminal “Grade 3s” (no defender had to be taken on and beaten to gain the score/free). Eight such scores against any side, let alone a Division 3 side, is simply too much.

On Sunday against Galway, from 17 points/scoreable frees/”45’s” conceded, a massive 10 were “Grade 3s”. Quite simply, Mayo once again conceded too many unnecessary scoreable frees, were pulled out of defensive position too easily, or simply didn’t track runs, and conceded scores.

There’s one striking pattern in this. The key Mayo player responsible for five of these Galway scores, where no man had to be taken on and beaten, was Séamus O’Shea. He only played 47 minutes.

For one, he made a completely unnecessary tackle and foul, for another he took up a position as a sweeper and allowed an unmarked man to kick the point, for another he simply didn’t track a runner who scored, for another he was sucked into the ball and “piggy in the middled” and for another, he dropped a short kick-out.

O’Shea fouls a man running into a wall defenders and a blanket defence

It’s man-on-man but O’Shea doesn’t track the run of the scorer

He was replaced by his brother Aidan O’Shea in the 47th minute. Within two minutes of his arrival, he had conceded two “Grade 3” points. For the first, he was caught completely the wrong side of a break off a kick-out and allowed his man to win the kick-out on the goal-side with a free run to goal. For the second, he made a completely unnecessary foul.

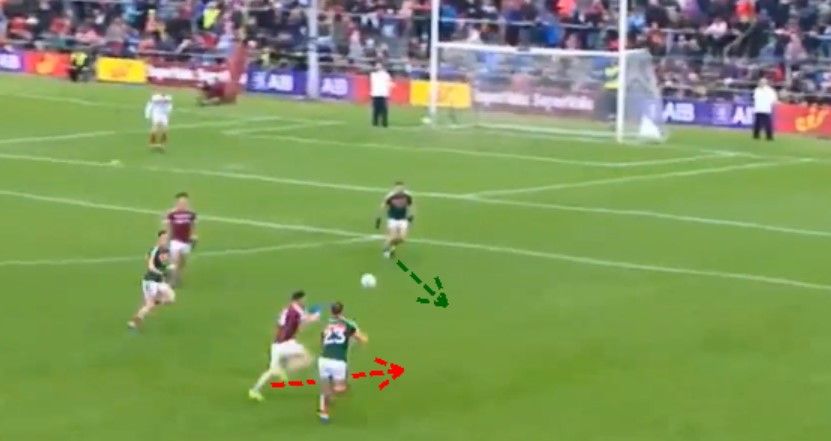

The kick-out is short, but Chris Barrett had the danger covered

But O’Shea made a completely unnecessary foul

In short, from 15 Mayo points conceded, seven came through two players who held one midfield position, and not one of the scores required Galway to take on and beat the man directly.

The flip side of Aidan O’Shea is that the two long kick-outs he competed for saw Mayo come away with the ball and he drew even at one break won and one lost. Séamus O’Shea competed for just one kick-out, which he lost.

Galway’s Defence

By contrast, Galway defended meticulously. They conceded just two “grade 3s”, both of which were extremely dubious refereeing decisions. Thomas Flynn’s black card incident accounted for one. Gareth Bradshaw fouled Tom Parson’s 64 metres from goal for the other, but Cillian O’Connor stole nine metres to kick the free from a scoreable 55.

Every other score required Mayo to take on and beat Galway defenders or saw Mayo turn Galway over high up the field.

The defensive structure and coaching of Kevin Walsh and his backroom team is worthy of huge praise. Time and again, Galway defenders tracked the correct Mayo run/covered the right space and systematically avoided making unnecessary contact.

Despite Any Moran getting past Declan Kyne and side stepping inside the next defender, nobody makes contact

And Kyne gets back to make the block

All in all, apart from playing 15 against 14, the key difference between the sides was the quality of Galway’s defending compared to Mayo’s.

Kick-outs

Startlingly, and once again, alluding to Galway’s defensive structures, from 21 Mayo kick-outs, they managed to create just a solitary point, a ratio of less than five percent. They scored just one from five quick, short kick-outs.

Interestingly, David Clarke tried three kick-outs to the half back line, and two ended up in Galway hands and over the bar. One simply missed its target, and while Séamus O’Shea won’t be happy with dropping another, it was an awkward ball, bouncing at his feet, with a man hot on his heels.

Perhaps the Hennelly/Clarke debate is more complex than it seems.

From nine long kick-outs, Mayo won five and lost four, but conceded two points directly off the four they lost, a 50 percent score concession ratio.

In total, counting the first possession, as well as first possession upon turnover, from all Mayo kick-outs, they scored one point and conceded seven. That’s an average score concession of 0.29 points per kick-out.

This was probably the most significant element to Galway’s numerical superiority. It allowed them to go man-on-man on Mayo’s kick-outs but still hold a sweeper.

It’s man-on-man, but Galway have a sweeper, circled

In fact, had Galway not won, you’d have been laying the blame on the ease with which they allowed a numerically inferior Mayo get off three short kick-outs in the second half when they had crucified them on long ones and efforts to the half back line, throughout the second half.

Galway’s total kick-out ratio wasn’t brilliant either, coming in at a net loss of a 0.11 points score concession per kick. Also interestingly, they tried one kick-out to the half back line. It ended up in their net.

Seán Armstrong’s Free taking

In a game of small margins, Armstrong’s dead ball accuracy was the difference. You couldn’t argue with Cillian O’Connor’s record. From three long distance frees and one tricky wide angled free on a terribly windy day, he scored two from four, a not unreasonable fifty percent tally.

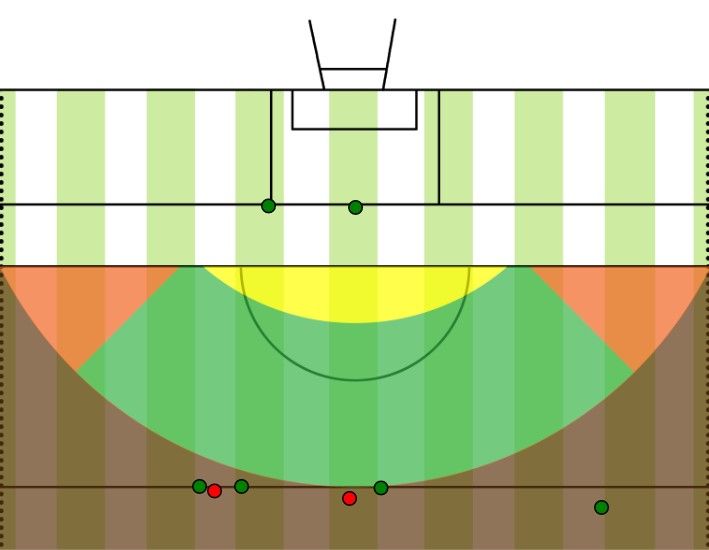

O’Connor’s free-kick map

Seán Armstrong’s kicking, however, was crucial. From six dead balls outside of 45 metres, he nailed four of them, coming in at 67 percent. A less impressive ratio and, crucially, Galway would possibly have trailed at half time, depriving them of the impetus to go onto a memorable victory.

Armstrong’s free-kick map

Stephen O’Meara is the creator and owner of www.gaaprostats.com, statistical and video analysis software designed specifically for Gaelic football and hurling.