Share

11th June 2018

05:40pm BST

Outside the Creighton Hotel, they're basking in the sunshine with pints in hand and worries out of sight. Four lads huddled on the street with their drinks seem to know every single Donegal man who walks by them and they have a joke to finish the conversation with each of them.

Even on the climb up to St. Tiernach's Park, everything is slow, easy. 'Awk aye' is resounded around the place at the start of every sentence, just a reassurance that you don't need to get yourself worked up, everything will be grand.

In the Gerry Arthur's stand, it feels like every Donegal person took the same bus down from the same village at the same time for some community day out where they'll mingle and talk to the person five rows back, they'll greet any stranger so they can find out where their ma grew up and what her maiden name was and they'll let their kids wander off with footballs and free spirits.

Your man with the bagpipes is there. He's always there, trawling the sidelines before games to entertain the crowd in his green blazer and gold kilt. If you listen carefully enough, you can make out the tune to Caledonia on fast forward until he turns to the supporters in the stand with one fist in the air and one almighty, 'Up Donegal!'

It always does the trick.

Outside the Creighton Hotel, they're basking in the sunshine with pints in hand and worries out of sight. Four lads huddled on the street with their drinks seem to know every single Donegal man who walks by them and they have a joke to finish the conversation with each of them.

Even on the climb up to St. Tiernach's Park, everything is slow, easy. 'Awk aye' is resounded around the place at the start of every sentence, just a reassurance that you don't need to get yourself worked up, everything will be grand.

In the Gerry Arthur's stand, it feels like every Donegal person took the same bus down from the same village at the same time for some community day out where they'll mingle and talk to the person five rows back, they'll greet any stranger so they can find out where their ma grew up and what her maiden name was and they'll let their kids wander off with footballs and free spirits.

Your man with the bagpipes is there. He's always there, trawling the sidelines before games to entertain the crowd in his green blazer and gold kilt. If you listen carefully enough, you can make out the tune to Caledonia on fast forward until he turns to the supporters in the stand with one fist in the air and one almighty, 'Up Donegal!'

It always does the trick.

Everything about this day and these people is pure, laid-back comfort, like being at home with the feet up, not worried about whether you need a coaster or not before planting your cup of tea down.

This must be what everyone thinks of when they think of Donegal. The best beaches in the world, serene scenery, pleasant people. Care-free. Only a Donegal man with bagpipes would have stewards at a major event obediently open gates for him so he can parade around every stand of the stadium, just for the craic.

You can become hypnotised by this way of life. Sure what would you ever have to worry about? Awk aye, it'll be grand.

You'd nearly forget there's a football match to be played and, Jesus, you'd forget even quicker that, during that match, what you'll see is anything but care-free or laid back or left in any way to chance.

Everything about this day and these people is pure, laid-back comfort, like being at home with the feet up, not worried about whether you need a coaster or not before planting your cup of tea down.

This must be what everyone thinks of when they think of Donegal. The best beaches in the world, serene scenery, pleasant people. Care-free. Only a Donegal man with bagpipes would have stewards at a major event obediently open gates for him so he can parade around every stand of the stadium, just for the craic.

You can become hypnotised by this way of life. Sure what would you ever have to worry about? Awk aye, it'll be grand.

You'd nearly forget there's a football match to be played and, Jesus, you'd forget even quicker that, during that match, what you'll see is anything but care-free or laid back or left in any way to chance.

Declan Bonner is a proud Donegal man but he's not in Clones to enjoy the atmosphere and he's certainly not there to relax. Everything about his team is meticulously prepared, every single facet of the game is worked out and thought through and it's obvious from how the Donegal players play ball that he is a very diligent thinker and harder worker.

From the moment Frank McGlynn goes down injured and there's not one but two physios sprinting onto the field alongside Karl Lacey as Michael Murphy has a word in the ref's ear, it's clear that there's an element of savvy game management going on. Everything today is on Donegal's terms. Total control.

Connaire Harrison is being sheep-dogged into corners by Neil McGee, for now, and Ryan McHugh is keeping tabs on wing back Darren O'Hagan. Outside of that, Declan Bonner won't have his side dictated to. Instead, they'll thrust everything they want onto the opposition and they'll do it in some of the most fascinating ways.

Michael Murphy

For as long as Neil Gallagher and Rory Kavanagh started to descend with age from the summit they had reached, the only tactical question that ever seemed to surround Donegal was whether or not they should play Michael Murphy at full forward or at midfield.

They had tried bringing him in and out during games but it felt like they were constantly robbing Peter just to pay Paul but, suddenly, Declan Bonner has seemingly found a way of actually playing Michael Murphy at midfield and at full forward at the same time.

You see, whilst Donegal have gotten praise for opening up and placing more emphasis on attack - because teams who defend too much automatically get criticised now - the manager hasn't actually abandoned that principle of defending in numbers.

For large parts of the game on Sunday, only Patrick McBrearty stayed forward for Donegal whilst the rest of them filtered back but, rather than relying on an outdated model of counter-attacking teams the length of a 140-metre pitch, Declan Bonner has his team slow the ball up until they're set up in attack. They keep possession in the opposition half, they go sideways and back if an obvious attack isn't on and, one by one, they completely dragged Down into a total defensive shape that they didn't want to be in but they simply had to be because of the bodies that Donegal committed.

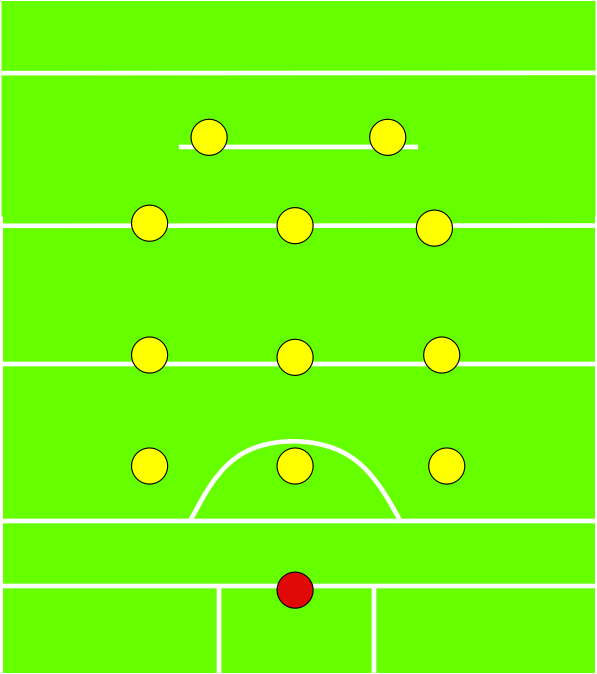

As Donegal held the ball between the half way line and the Down 45', their players filed into attack and set up like this.

Declan Bonner is a proud Donegal man but he's not in Clones to enjoy the atmosphere and he's certainly not there to relax. Everything about his team is meticulously prepared, every single facet of the game is worked out and thought through and it's obvious from how the Donegal players play ball that he is a very diligent thinker and harder worker.

From the moment Frank McGlynn goes down injured and there's not one but two physios sprinting onto the field alongside Karl Lacey as Michael Murphy has a word in the ref's ear, it's clear that there's an element of savvy game management going on. Everything today is on Donegal's terms. Total control.

Connaire Harrison is being sheep-dogged into corners by Neil McGee, for now, and Ryan McHugh is keeping tabs on wing back Darren O'Hagan. Outside of that, Declan Bonner won't have his side dictated to. Instead, they'll thrust everything they want onto the opposition and they'll do it in some of the most fascinating ways.

Michael Murphy

For as long as Neil Gallagher and Rory Kavanagh started to descend with age from the summit they had reached, the only tactical question that ever seemed to surround Donegal was whether or not they should play Michael Murphy at full forward or at midfield.

They had tried bringing him in and out during games but it felt like they were constantly robbing Peter just to pay Paul but, suddenly, Declan Bonner has seemingly found a way of actually playing Michael Murphy at midfield and at full forward at the same time.

You see, whilst Donegal have gotten praise for opening up and placing more emphasis on attack - because teams who defend too much automatically get criticised now - the manager hasn't actually abandoned that principle of defending in numbers.

For large parts of the game on Sunday, only Patrick McBrearty stayed forward for Donegal whilst the rest of them filtered back but, rather than relying on an outdated model of counter-attacking teams the length of a 140-metre pitch, Declan Bonner has his team slow the ball up until they're set up in attack. They keep possession in the opposition half, they go sideways and back if an obvious attack isn't on and, one by one, they completely dragged Down into a total defensive shape that they didn't want to be in but they simply had to be because of the bodies that Donegal committed.

As Donegal held the ball between the half way line and the Down 45', their players filed into attack and set up like this.

So, whilst they did have Murphy out around the middle of the pitch, fetching kickouts, directing play and filling gaps at the back, by holding onto the ball and allowing themselves to take shape in attack, they were then able to get Murphy in alongside McBrearty and Jamie Brennan in the full forward line.

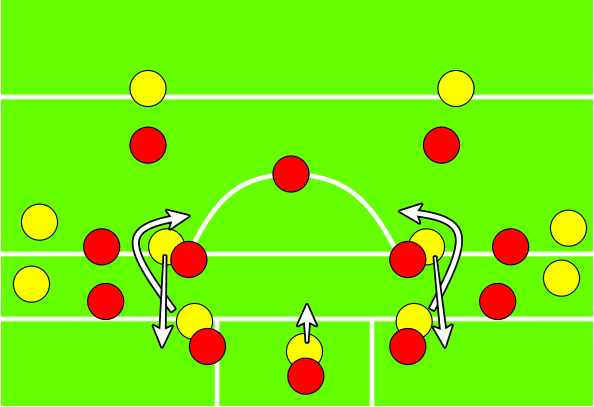

But, there, Down weren't able to just plant men in front of them and stop ball going in. Donegal had so many options which they were willing to take but how the players rotated in and out of these positions dragged defenders all over the place whilst the one constant that remained was Murphy who was usually making hay then when the gap opened up.

So, whilst they did have Murphy out around the middle of the pitch, fetching kickouts, directing play and filling gaps at the back, by holding onto the ball and allowing themselves to take shape in attack, they were then able to get Murphy in alongside McBrearty and Jamie Brennan in the full forward line.

But, there, Down weren't able to just plant men in front of them and stop ball going in. Donegal had so many options which they were willing to take but how the players rotated in and out of these positions dragged defenders all over the place whilst the one constant that remained was Murphy who was usually making hay then when the gap opened up.

A bit of movement, a bit of rotation and, even with 13 men back behind the ball - everyone except O'Hare and Harrison - Down couldn't block that gap sitting in front of Murphy and, yet again, another team couldn't stop McBrearty and Brennan coming on the loop.

That shape was important for Donegal. At one stage, mid-attack, McBrearty seemed to be lamenting Ciaran Thompson for not coming up and filling in the positions that needed filling. Even after they had scored, they were having words. It didn't matter who took up each of these slots, as long as they were taken up and as long there were options and avenues to spin Down heads.

As Donegal attacked, you could see Brendan McArdle growing nervous with McBrearty on his hands, anticipating that anything might happen but, after a while, you knew that ball wasn't going in, not until Donegal were ready. Still, McArdle couldn't relax.

Just before half time, Bonner sent every man back. They abandoned the pressure they were putting on for the kickouts and they set up camp. No goals was the message and it was another instruction followed to the letter.

The kickout

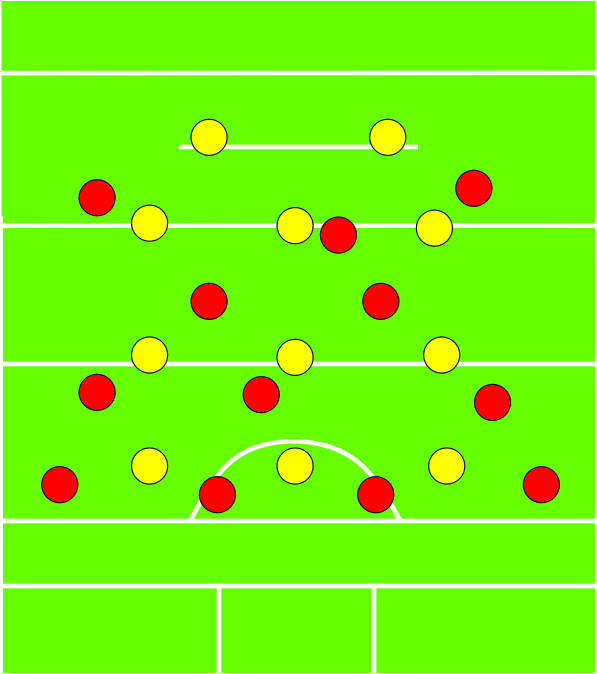

Donegal won eight of Down's first 10 kickouts and they did it by studying where Marc Reid wanted to place it. Then, they attacked that space.

11 men they generally committed to contesting the opposition kickout and it paid rich dividends as they reeled off 1-8 without reply - 1-4 of those coming with 14 men.

Even with a man less, they still kept this shape for Down's kicks.

A bit of movement, a bit of rotation and, even with 13 men back behind the ball - everyone except O'Hare and Harrison - Down couldn't block that gap sitting in front of Murphy and, yet again, another team couldn't stop McBrearty and Brennan coming on the loop.

That shape was important for Donegal. At one stage, mid-attack, McBrearty seemed to be lamenting Ciaran Thompson for not coming up and filling in the positions that needed filling. Even after they had scored, they were having words. It didn't matter who took up each of these slots, as long as they were taken up and as long there were options and avenues to spin Down heads.

As Donegal attacked, you could see Brendan McArdle growing nervous with McBrearty on his hands, anticipating that anything might happen but, after a while, you knew that ball wasn't going in, not until Donegal were ready. Still, McArdle couldn't relax.

Just before half time, Bonner sent every man back. They abandoned the pressure they were putting on for the kickouts and they set up camp. No goals was the message and it was another instruction followed to the letter.

The kickout

Donegal won eight of Down's first 10 kickouts and they did it by studying where Marc Reid wanted to place it. Then, they attacked that space.

11 men they generally committed to contesting the opposition kickout and it paid rich dividends as they reeled off 1-8 without reply - 1-4 of those coming with 14 men.

Even with a man less, they still kept this shape for Down's kicks.

So, like a puppet on a string, Declan Bonner was able to throw Down into positions they didn't want to be in. By adopting a 5-3-3 formation inside the opposition half, Down yet again ended up with 13 men drawn back looking for space but, taking up a zonal shape and hunting in packs when the ball was in the air, Down got completely suffocated and put on the back foot time and time again.

So, like a puppet on a string, Declan Bonner was able to throw Down into positions they didn't want to be in. By adopting a 5-3-3 formation inside the opposition half, Down yet again ended up with 13 men drawn back looking for space but, taking up a zonal shape and hunting in packs when the ball was in the air, Down got completely suffocated and put on the back foot time and time again.

When Reid finally went short to the spare man for the first time in the half (after Donegal had reeled off 1-8), there were wild, ironic cheers from the crowd and, funnily enough, Down went straight up and kicked their first score of the game too.

But they did that by playing a game they didn't want to play.

Down want to open up, they want to be adventurous and go for the jugular but found themselves thrust into situations they couldn't get out of.

Connaire Harrison, despite losing Neil McGee very early on, got next to nothing by way of productive delivery into him and he was growing visibly frustrated, gesturing towards Eamon Burns on the sideline, cracking up when his team lost the ball and, at one stage, looking unhappy at a shite throw of a water bottle in from the side that went right over his head. It summed up Down's day and it was testament to how their rivals from the north west had the measure of them.

Meanwhile, McBrearty and Brennan were looping off the shoulder of ball-winners, Ryan McHugh and Frank McGlynn were darting through the middle and, with less men, Hugh McFadden was still able to man the edge of the small square late on. Everything you would've expected Donegal to do, they did it, but they did it because they set the terms of engagement.

It might've been pleasant and cordial in the stands, everything might've been a bit of craic and, awk aye, all grand too, but, on the pitch, Declan Bonner unleashed a very different Donegal. A ruthless, tireless operation working through set plays with cut-throat efficiency. He's thought of every scenario and, in those, he's thought of the smartest ways to still get the best out of his best players.

Because of his meticulous preparation, his military planning and even his overthinking, Donegal are finding their way back to the big time again with a new regime. A controlled regime.

But, because of that control, Christy Murray from Raphoe is able to wander the sidelines freely with his bagpipes right into the depths of summer.

When Reid finally went short to the spare man for the first time in the half (after Donegal had reeled off 1-8), there were wild, ironic cheers from the crowd and, funnily enough, Down went straight up and kicked their first score of the game too.

But they did that by playing a game they didn't want to play.

Down want to open up, they want to be adventurous and go for the jugular but found themselves thrust into situations they couldn't get out of.

Connaire Harrison, despite losing Neil McGee very early on, got next to nothing by way of productive delivery into him and he was growing visibly frustrated, gesturing towards Eamon Burns on the sideline, cracking up when his team lost the ball and, at one stage, looking unhappy at a shite throw of a water bottle in from the side that went right over his head. It summed up Down's day and it was testament to how their rivals from the north west had the measure of them.

Meanwhile, McBrearty and Brennan were looping off the shoulder of ball-winners, Ryan McHugh and Frank McGlynn were darting through the middle and, with less men, Hugh McFadden was still able to man the edge of the small square late on. Everything you would've expected Donegal to do, they did it, but they did it because they set the terms of engagement.

It might've been pleasant and cordial in the stands, everything might've been a bit of craic and, awk aye, all grand too, but, on the pitch, Declan Bonner unleashed a very different Donegal. A ruthless, tireless operation working through set plays with cut-throat efficiency. He's thought of every scenario and, in those, he's thought of the smartest ways to still get the best out of his best players.

Because of his meticulous preparation, his military planning and even his overthinking, Donegal are finding their way back to the big time again with a new regime. A controlled regime.

But, because of that control, Christy Murray from Raphoe is able to wander the sidelines freely with his bagpipes right into the depths of summer.Explore more on these topics: