Share

11th June 2016

06:05pm BST

One day, it just clicked for Seamus Coleman. One day, his chance came along like a bolt from the blue and he jumped all over it like a savage. He's never looked back. He won't look back.

He's been railing against perceptions his whole life; history even. You don't get men like Seamus Coleman lying around a small fishing village like Killybegs very often.

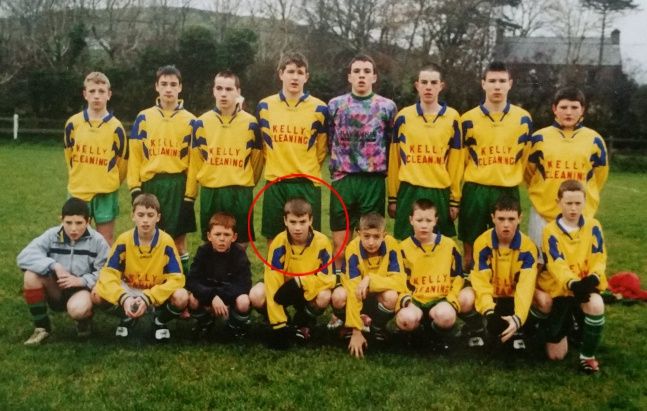

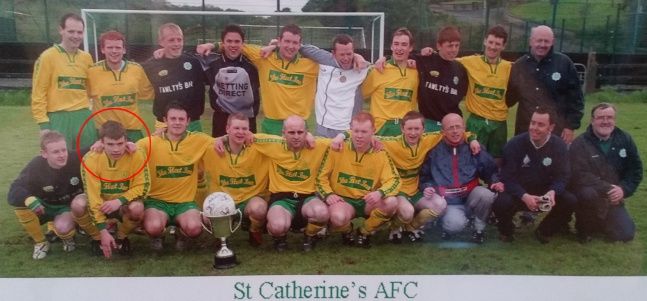

You don't really expect a humble club like St. Catherine's, serving football to the 1,500-strong community, to one day produce future international captains.

Declan Boyle came along and made it as far as Celtic. He had a stint with their reserves and he retired seven years ago, a legend of Finn Harps and Derry City. Shaun Kelly got to Hearts and they take pride of the pair in Killybegs, and so they should.

Neither managed to just take that next step though and really push on. Coleman did. And he's on the verge of another one.

One day, it just clicked for Seamus Coleman. One day, his chance came along like a bolt from the blue and he jumped all over it like a savage. He's never looked back. He won't look back.

He's been railing against perceptions his whole life; history even. You don't get men like Seamus Coleman lying around a small fishing village like Killybegs very often.

You don't really expect a humble club like St. Catherine's, serving football to the 1,500-strong community, to one day produce future international captains.

Declan Boyle came along and made it as far as Celtic. He had a stint with their reserves and he retired seven years ago, a legend of Finn Harps and Derry City. Shaun Kelly got to Hearts and they take pride of the pair in Killybegs, and so they should.

Neither managed to just take that next step though and really push on. Coleman did. And he's on the verge of another one.

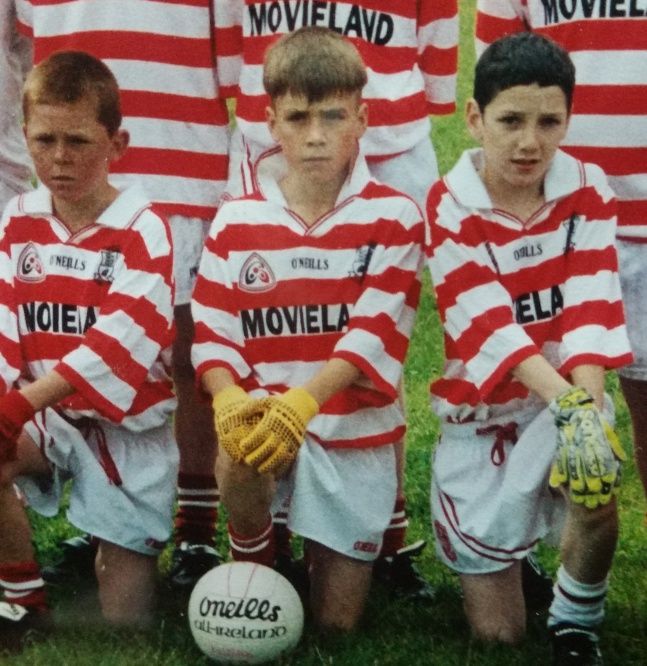

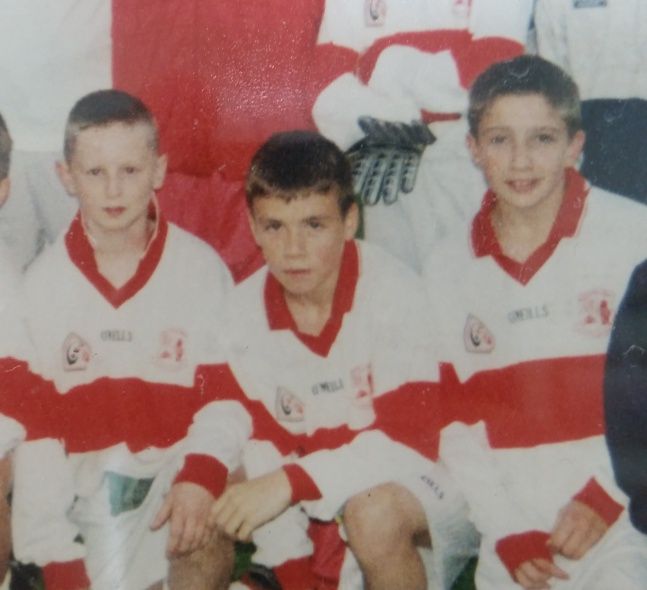

It's probably a product of his upbringing. His mother is a Glen/Kilcar woman from the Gaeltacht area of the county. His uncles were all big, strong, robust men who wouldn't even think about lying down. Even his older brothers excelled. Francis was a decorated GAA player before he joined the army and Stevie was actually the first of the Coleman clan to don the green of Ireland when he represented his country in the Special Olympics.

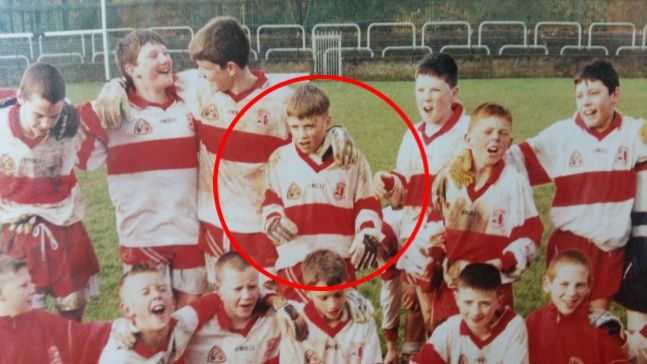

Seamus was brought up in a tough, proud Gaelic family, taking hits in age groups above him, forced to hold his own on the once mud-laden Emerald Park.

Outside of that world, he was growing up on Cummins Hill, a densely populated housing estate not far from St. Catherine's FC's home - his first football club.

If he wasn't going to toughen up as the wee man in the Donegal leagues, he would do it pretty damn quickly on the street. Or in the inter-estate grudge matches, mostly between Coleman's Circle and the other lot's Straight (those were the shapes of their respective estates).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Skp5TE0R8P0

It's probably a product of his upbringing. His mother is a Glen/Kilcar woman from the Gaeltacht area of the county. His uncles were all big, strong, robust men who wouldn't even think about lying down. Even his older brothers excelled. Francis was a decorated GAA player before he joined the army and Stevie was actually the first of the Coleman clan to don the green of Ireland when he represented his country in the Special Olympics.

Seamus was brought up in a tough, proud Gaelic family, taking hits in age groups above him, forced to hold his own on the once mud-laden Emerald Park.

Outside of that world, he was growing up on Cummins Hill, a densely populated housing estate not far from St. Catherine's FC's home - his first football club.

If he wasn't going to toughen up as the wee man in the Donegal leagues, he would do it pretty damn quickly on the street. Or in the inter-estate grudge matches, mostly between Coleman's Circle and the other lot's Straight (those were the shapes of their respective estates).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Skp5TE0R8P0

"When you live in a housing estate you kind of have to get tough quicker than normal," John Conwell watched 'Seamie' grow up on Cummins Hill and he was coaching the same boy as soon as he joined the St. Catherine's setup. "When you’re outside playing with the older boys and they’re starting to shove you around, you have to harden up. "He wouldn’t let nobody bully him, he’d be a tough wee boy and he’d stand his ground which you can see in his games now, he doesn’t stand back and let the bigger name players step over him. He’ll let them know that he’s there and not to mess with him."Drive. Aggression. Determination.

If you talk to anyone in Killybegs about Seamus Coleman, you'll hear those three adjectives used almost instantly. His people recall stories of the Everton star with a glint in their eyes. It's almost as if the bite that he brought to his sport is still palpable on the south coast of Donegal.

If you talk to anyone in Killybegs about Seamus Coleman, you'll hear those three adjectives used almost instantly. His people recall stories of the Everton star with a glint in their eyes. It's almost as if the bite that he brought to his sport is still palpable on the south coast of Donegal.

"It was just in him," Conwell explained. "He had that drive in him and that’s it. Whatever sport he played, he had that drive – it wasn’t just the Gaelic or the soccer. If you were playing out in the yard, we used to play a game called curby where you had to throw the ball off the curb and he’d still want to be the best at that as well. It’s a good asset to have."It wasn't the only asset he had. Everywhere Coleman went, a football came with him. If he wasn't playing a game, he was looking to play a game. Conwell still remembers kicking out the back with his brother and a little blonde head peering over the wall, begging to join in.

“He didn’t leave the football alone," the St. Catherine's coach said. "You’d go back home from training, look out the window and he’d be there kicking ball again. He always had a football with him. Playstation and stuff wouldn’t have been as big and there were loads of kids, loads of us growing up at the same time on the estate and any time there was daylight or good weather, we were out. You never sat inside. “That’s what he did: Football all the time. Whether it was Gaelic or the soccer, he always, always had the ball. He was looking to play ball, he was looking to join in with us, he always wanted to play ball. “Technically, he wouldn’t have been the best player – his touch and things like that. Our coaching back then wouldn’t have been as developed as it is now, around here anyway. We would’ve had a day in the week to train and it would’ve been basic passing drills and stuff. Seamie had to work hard on his touch and his passing and his positional play a bit. Where maybe some other players in the club just naturally had it, he had to work a wee bit harder."So he worked. He kicked ball after training, he kicked it on the street after after-training and he asked questions and learned. By the time he got to Sligo, he was the first one to show up and the last one to leave.

Now, Coleman is a superstar recognised the continent over. He's really the only one in the Ireland squad right now with genuine big-club distinction. He's been thrilling Everton fans for seven years but now people talk about him and mention clubs like Bayern Munich, like Manchester United and City. Now they talk about him as one of the best full backs in the world.

Still, when he comes home, he's just Seamie from the estate.

Now, Coleman is a superstar recognised the continent over. He's really the only one in the Ireland squad right now with genuine big-club distinction. He's been thrilling Everton fans for seven years but now people talk about him and mention clubs like Bayern Munich, like Manchester United and City. Now they talk about him as one of the best full backs in the world.

Still, when he comes home, he's just Seamie from the estate.

"When Seamie comes home in the summer and the kids know he's home, they’d be over knocking on his door asking him to come out and play. And he’d still come out, he’d take the ball with him and they’d play a game of sides and Seamie would be playing ball with them," Conwell told the tale of the 'homebird'. "Once word gets out that Seamie is home, more and more kids from further away would all show up and they’d be looking in to see if they could get a game and he’d be playing ball with kids from 6 and 7 right up to a few adults joining in as well. He just wants the kids to experience what he experienced growing up."https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zn3gn2PNkqc

“There was a very quiet wittiness about him," Peter McGinley took the Irish international at under-10s and again at minors. "When he talked or had a bit of banter, it meant something more. "He would eye up everything around him and when it came around to the one-liners, he was very, very good. He was a good ol’ laugh in the changing room and would always be in the middle of the pranks on the bus and that."He got away with it though. Not just because it was good-natured, but because he was one of the best players in the team - nae, county.

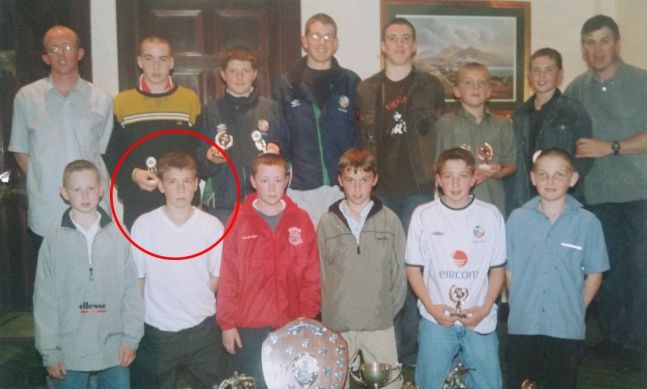

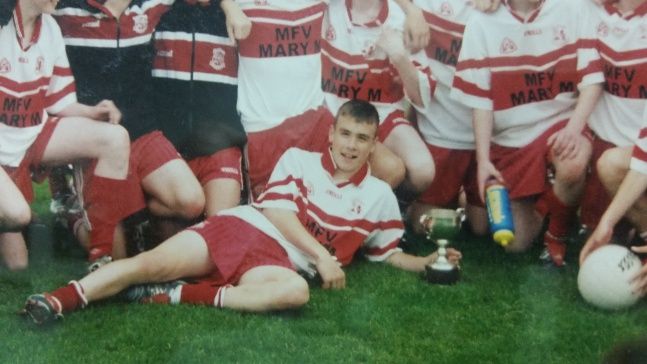

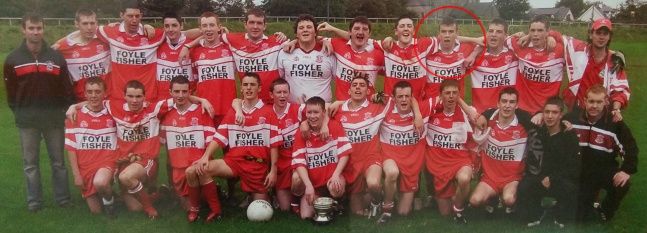

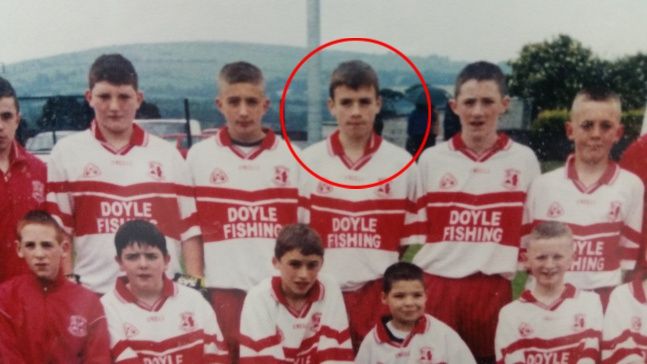

From his primary school days at Niall Mór National School, Coleman was sweeping up Gaelic Football trophies like they were going out of fashion. With his club overlooking the scenic Fintra beach, he was winning county championships from under-12. Winning became a habit.

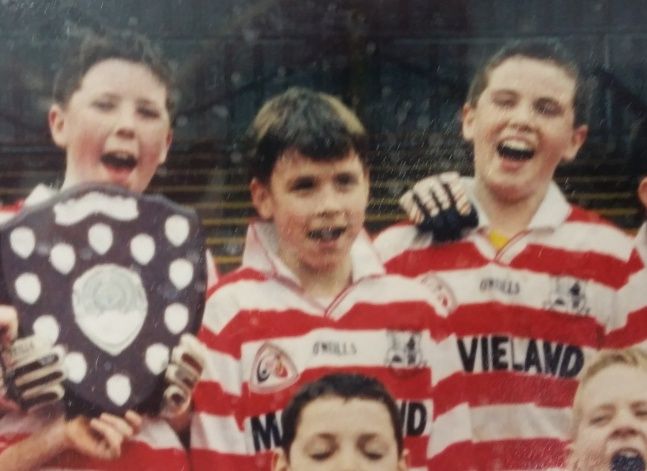

At under-14s, they clinched the Donegal Féile, they went on and won the championship again at under-16 before back-to-back minor titles and a showdown with Donegal All-Ireland winner Leo McLoone.

From his primary school days at Niall Mór National School, Coleman was sweeping up Gaelic Football trophies like they were going out of fashion. With his club overlooking the scenic Fintra beach, he was winning county championships from under-12. Winning became a habit.

At under-14s, they clinched the Donegal Féile, they went on and won the championship again at under-16 before back-to-back minor titles and a showdown with Donegal All-Ireland winner Leo McLoone.

"The second minor championship, in the final, Leo McLoone was causing havoc in the first half and Seamie went back to mark him. Seamie would’ve been man of the match that day in the final and he would’ve possibly been playing for Sligo Rovers at the same time. "Glenties were definitely the better team in the first half but Seamie changed everything. "He wouldn’t have been the tallest but he was in and around the middle and he just really took the game to Glenties. That was a very impressive performance that day."

It got to the stage though where Coleman's soccer career was starting to take off and McGinley admitted that he was only hoping he'd have his star for the big games.

Where he once prioritised Gaelic Football, Seamie was now giving professional sport a lash but his influence on the GAA field never waned and he was thrown into the Killybegs senior side as soon as they could get him in.

It got to the stage though where Coleman's soccer career was starting to take off and McGinley admitted that he was only hoping he'd have his star for the big games.

Where he once prioritised Gaelic Football, Seamie was now giving professional sport a lash but his influence on the GAA field never waned and he was thrown into the Killybegs senior side as soon as they could get him in.

"He would’ve been playing for the seniors at that time, 16 going on 17," McGinley revealed. "He was an attacking half back for them but he actually ended up with a few man-marking jobs. I remember Adrian Sweeney was down here for a league match and he was playing well for Donegal at that stage and Seamie marked him out of the game. "When you were a couple of points down, he was the man you wanted. "No matter where he was playing, he would always chip in with a few scores, even if he was doing a man-marking job. "Michael Murphy has said he remembers a minor league final when Glenswilly played Killybegs, Murphy was centre half forward and Seamie was centre half back marking him but Michael Murphy said he spent most of the game marking Coleman. "He wouldn’t have been the biggest on the team but he would’ve been one of the main players in and around centre half back – a very, very tenacious, attacking footballer."

McGinley is almost insulted to be asked if Coleman could've played for the Donegal senior side: "Ah, definitely. Definitely."

Still, Seamie keeps that connection strong. In an interview with the Irish Times recently, he revealed that all he wants to do when he's finished playing professional football is return to Killybegs and play with St. Catherine's again and play with his GAA club again.

They're building a house in the Fintra area, getting to training on a Tuesday and Thursday night will be easy for him.

McGinley is almost insulted to be asked if Coleman could've played for the Donegal senior side: "Ah, definitely. Definitely."

Still, Seamie keeps that connection strong. In an interview with the Irish Times recently, he revealed that all he wants to do when he's finished playing professional football is return to Killybegs and play with St. Catherine's again and play with his GAA club again.

They're building a house in the Fintra area, getting to training on a Tuesday and Thursday night will be easy for him.

“Any time he’s at home, if he’s back for a month or two in the summer, he’d be up kicking about with the under-8s and under-10s and up giving them a few wee words. That’s the kind of modest type of a fella he is."

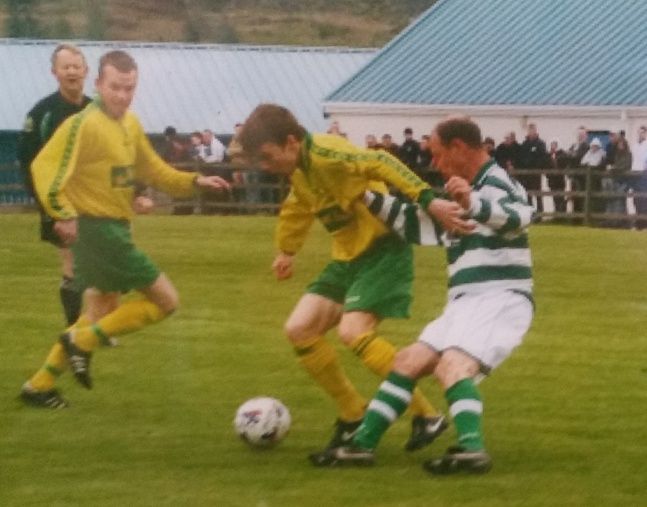

"Once upon a time, one day, it just came... like that."John Conwell doesn't even know how it all really happened. No-one's too sure. St. Catherine's hosted a friendly with Sligo Rovers one fateful February day and Seamus Coleman took to the 45 minutes he was given like they were his one and only chance of making it. He never let one second pass him by. He wouldn't let that happen. He couldn't let that happen.

Brian Dorrian was the manager that day back in 2006 and he was more concerned with the game with Kilmacrennan Celtic the next day, one they needed to win heading into the penultimate fixture of their league-winning season.

So he mixed the team up but, for his half, Seamus Coleman was thrown into centre half alongside Mark Boyle to keep an eye on the distinguished pairing of Sean Flannery and Paul McTiernan who, between them, had amassed 30-odd goals the season previous.

Brian Dorrian was the manager that day back in 2006 and he was more concerned with the game with Kilmacrennan Celtic the next day, one they needed to win heading into the penultimate fixture of their league-winning season.

So he mixed the team up but, for his half, Seamus Coleman was thrown into centre half alongside Mark Boyle to keep an eye on the distinguished pairing of Sean Flannery and Paul McTiernan who, between them, had amassed 30-odd goals the season previous.

"He didn’t give the boys a kick. He didn’t give them a touch," Dorrian recalled. "I happened to be working with Paul McTiernan at Sligo a few years later and he was telling me that after that game he actually said to Sean Connor [the Rovers manager], ‘Jesus, that boy’s giving me as hard a time as I’ve ever had in the League of Ireland.'"Coleman was like a dog with a bone. At it the whole time. Relentlessly. If McTiernan found it tough, Sean Flannery wasn't enjoying his afternoon in Killybegs either.

"Flannery was built. He was your old-school centre forward – big, strong, square shoulders, get the ball into his feet and he’d toss all around him," John Conwell stood on the line with Dorrian watching history unfold. "But that day, Seamie didn’t give him a sniff. Even on the physical aspects, he didn’t let him toss him over, he was out in front of him and he didn’t give him the living of a dog that day."Within 30 minutes, Sligo manager Sean Connor had the idea of Sligo Rovers sold to Coleman. He met with the teenager and his parents and coaches straight after the game in the Emerald Park changing rooms and he wouldn't leave until he had the player signed up. Finn Harps' advances were soon dwarfed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=utIrXT-HBzM

“He had a serious work ethic and that never say die kind of thing inside him," Brian Dorrian would be reunited with his Killybegs prospect at Sligo a year after Coleman moved to the Showgrounds. “If some man beat him on the pitch, the next time around the same player wouldn’t do the same thing again to him. He had that non-defeatist attitude. If something was to go wrong, he’d work harder the next time to rectify it. “That’s the way he always was and over time it showed in his ability and his aggression. He would start carrying games to teams then, he was good on the ball, running with it, he was very, very fast and he wasn’t a big lad then – he was very slight – but he was very, very tough. “There’d be a lock of ol’ slapping going on and the odd kick and he was well fit to handle it. He’d get up and he’d get on with it and it wouldn’t be a problem. “There was always something there. I think when he played Gaelic Football it was the same, he was a very good athlete. Technically, he wouldn’t light the world on fire when he was younger but he worked very hard on his game and you can see now he’s technically very good with working at a very high coaching level in England."

In 2006, Coleman was sitting his Leaving Cert but his football career was making huge strides in rapid quick time. Dorrian had him playing everywhere, all over defence, on the wing, he was up front earlier in his career and the day St. Catherine's clinched the league after Seamie had already agreed to join Sligo, he was playing in centre midfield.

In 2006, Coleman was sitting his Leaving Cert but his football career was making huge strides in rapid quick time. Dorrian had him playing everywhere, all over defence, on the wing, he was up front earlier in his career and the day St. Catherine's clinched the league after Seamie had already agreed to join Sligo, he was playing in centre midfield.

"We always knew he had ability but if anybody tells you they knew he was going to get to where he is, I would think that they’re telling you lies," Dorrian said. "Nobody knows what’s around the corner but he worked extremely hard to get the where he is and anything he gets out of it, he deserves. “He was very, very touted, touted in the end - in the GAA as well - because he was just a very special player, a dual player, and everybody was after him. But he chose to go to Sligo."

"There was never a moment with him where I thought ‘wow’," the new manager wasn't much of a fan of Coleman's.

McDonald wanted to play a 4-3-3 with Rovers and he didn't see where the Donegal man would fit into his team. His tenure was short-lived too but he set his plans in place and Coleman was not a part of them.

McDonald wanted to play a 4-3-3 with Rovers and he didn't see where the Donegal man would fit into his team. His tenure was short-lived too but he set his plans in place and Coleman was not a part of them.

"Defensively, he wasn’t the best back then, and positionally too," the former PSV player said. "You could say that those are still the parts of his game where he’s not at his best now. "Seamus was really shy, and I mean really shy. I just looked at him and thought ‘do you really want this? "I had my doubts, but I’m pleased to say he’s proved me wrong."But McDonald's questionable player judgment was extending beyond the yet unproven youngster from Killybegs. Paul McTiernan and Sean Flannery were let go under his stewardship and local stalwarts like Michael McNamara and Conor O'Grady were also told that they had no future at Sligo whilst McDonald was in charge. What he didn't know either was that Coleman wanted it more than any of them.

He was making the journey up and down from Killybegs every time for training and he had organised with team mates Gavin Peers and Keith Foy to stay with them in Sligo the night before a game.

He wasn't going to get much chances under McDonald though but his luck soon changed before the 2007/08 season began.

He was making the journey up and down from Killybegs every time for training and he had organised with team mates Gavin Peers and Keith Foy to stay with them in Sligo the night before a game.

He wasn't going to get much chances under McDonald though but his luck soon changed before the 2007/08 season began.

“When Rob left, there were two local fellas who have been kind of overlooked. They took over as caretaker, Dessie Cawley from Sligo and Leo Tierney from Mayo. They gave Seamie a chance. They made him a regular in the team at right back. They really took the first kind of gamble on him," a Rovers man to the core, Keith O'Dwyer was Club Promotions Officer for over five years at The Showgrounds. "Once Paul Cook came in, he recognised straight away that there was a diamond in the rough here. Seamie just had the right attitude. He’d be one of the last lads to leave training, especially when Paul Cook came in, he was so hungry to improve himself and to learn. "Paul had played at the top level, he played in the Premier League with Wigan and had a great career in England and he knew that. "I think Paul saw as well that this is a lad who has the potential to play at a higher level. At Rovers, we all kind of had that impression as well. I suppose the biggest question we had was how far he could go. "There was no doubt that there was a bit more about him."Not that Rob McDonald ever saw it.

One of Cook's first appointments was to bring Brian Dorrian from Killybegs and get him on board as reserve team manager.

Only a year had passed since Coleman had moved on from St. Catherine's but, by the time his old manager had caught up with him, he was a changed player.

One of Cook's first appointments was to bring Brian Dorrian from Killybegs and get him on board as reserve team manager.

Only a year had passed since Coleman had moved on from St. Catherine's but, by the time his old manager had caught up with him, he was a changed player.

"Paul Cook came in and automatically fancied him because he had this real work ethic and never say die attitude and Paul Cook himself really related to that, I think with the way he played himself. "He progressed really quickly. His physicality was better, his touch and fitness – he was a lot stronger and very fit. He was very fit anyway but he became a lot sharper and you could see with the first four or five games that he played, it took him a wee while to get used to it. He worked really, really hard at his technical side too."

All of a sudden, Coleman was part of this twin full back threat - along with Chris Butler on the left - that was thrilling Sligo fans. The duo were key to the way Paul Cook - now Portsmouth manager - wanted to play. Coleman marauded down the right, Butler at the other side and they went at teams from deep. The Donegal man thrived.

All of a sudden, Coleman was part of this twin full back threat - along with Chris Butler on the left - that was thrilling Sligo fans. The duo were key to the way Paul Cook - now Portsmouth manager - wanted to play. Coleman marauded down the right, Butler at the other side and they went at teams from deep. The Donegal man thrived.

"When he was at Sligo, he was so hungry," O'Dwyer said. "He was like a sponge. The first thing Paul Cook did was set Sligo up the way he wanted to play. He gave Seamus a free licence to run up and down the right wing, bomb on, bomb on, bomb. Maybe the defensive side of it, Everton kind of fine-tuned. "But the culture that Paul Cook fostered at The Showgrounds was, if Seamus made a mistake, he wasn’t going to be lambasted or castigated. It happens, let’s get on, and you run on and bomb down the wing again."By 2008, the vultures were circling. Clubs across the water were coming knocking for Seamus Coleman but, although David Moyes hadn't actually seen him play at all, it was Everton who best offer on the table for Sligo and, on the advice of club scout Mick Doherty - whose son was playing with Sligo at the time - the Merseyside outfit brought Coleman across the water in January 2009.

"We actually did really well," O'Dwyer said. "The only thing we didn’t do well was a sell-on clause, we got no sell-on clause. It wasn’t offered by Everton, it wasn’t on the table and they weren’t for negotiating it."60 grand, 250 grand, whatever - when it came down to it, Everton's was the best deal.

"Celtic made a very low offer – I think it was around a four-figure sum and a friendly. Birmingham offered something like 40,000. Crystal Palace wanted to take him on trial a couple of times. "At the time, like a lot of other League of Ireland clubs – and you wish you could say otherwise – we needed the money and we needed the money fast. "That money coming in and the clauses that came in after, they were huge contributions to the success that we had, in the way we were able to build up our first-team squad and it had a spin-off effect in the development of the ground. His leaving coincided with our most successful ever spell as a club."

The early reports feeding back to Sligo was that Seamus Coleman was being Seamus Coleman.

He was spending extra time on the training pitch, he was working with the defensive coaches there to see what he had to do to improve and, when it was recommended that he got some game time with Blackpool the following March, he jumped at the chance.

Then he led them to Wembley. Then he helped them to promotion.

The early reports feeding back to Sligo was that Seamus Coleman was being Seamus Coleman.

He was spending extra time on the training pitch, he was working with the defensive coaches there to see what he had to do to improve and, when it was recommended that he got some game time with Blackpool the following March, he jumped at the chance.

Then he led them to Wembley. Then he helped them to promotion.

By the summer of 2010, he was all over David Moyes' radar and, unknown to them then, he was about to give Everton fans and followers of the Premier League alike the surprise of their lives.

https://twitter.com/masterlee/status/27641307803

"I’m forever saying how surreal all of this seems to me at times," Coleman admitted in one of the Everton programmes this year.

But it's no fairytale. It's no fluke or magic. This has been the product of drive. Aggression. Determination.

It's been the product of Killybegs and the Coleman family. Following in the footsteps of older brother Stevie who likes to remind the youngest sibling that he was the first of them to represent his country but St. Catherine's have a place for both on the clubhouse wall.

By the summer of 2010, he was all over David Moyes' radar and, unknown to them then, he was about to give Everton fans and followers of the Premier League alike the surprise of their lives.

https://twitter.com/masterlee/status/27641307803

"I’m forever saying how surreal all of this seems to me at times," Coleman admitted in one of the Everton programmes this year.

But it's no fairytale. It's no fluke or magic. This has been the product of drive. Aggression. Determination.

It's been the product of Killybegs and the Coleman family. Following in the footsteps of older brother Stevie who likes to remind the youngest sibling that he was the first of them to represent his country but St. Catherine's have a place for both on the clubhouse wall.

It's been in the making since October 11 1988 and it's a simple story of hard work. The story of a boy who just didn't like to lose and the inspirational story of a Donegal man who seized the day.

"When it comes down to it, you only get one opportunity to make it as a professional soccer player and, when that opportunity comes, you have to take it."

Seamus Coleman took his shot and John Conwell and everyone else in attendance will never forget that day in Emerald Park in February 2006.

Neither will the rest of Ireland. On the cusp of his first major international tournament, Coleman isn't going in as a wildcard. He's going in as a leader. He's going in as the best right back in the world.

It's been in the making since October 11 1988 and it's a simple story of hard work. The story of a boy who just didn't like to lose and the inspirational story of a Donegal man who seized the day.

"When it comes down to it, you only get one opportunity to make it as a professional soccer player and, when that opportunity comes, you have to take it."

Seamus Coleman took his shot and John Conwell and everyone else in attendance will never forget that day in Emerald Park in February 2006.

Neither will the rest of Ireland. On the cusp of his first major international tournament, Coleman isn't going in as a wildcard. He's going in as a leader. He's going in as the best right back in the world.

He's going in with his tough-tackling menace defending right off the streets of south west Donegal almost overtaking his explosive trademark lung-bursting runs upfield now.

He's going in as the complete full back with the eyes of the continent tracking his movements.

He's one of Everton's best players, he is Ireland's best player and his next step would be the last one. His next step would be to the very top.

But, if we've learned anything over the last 10 years, no-one is better placed to take it. No-one is hungrier for it.

He's going in with his tough-tackling menace defending right off the streets of south west Donegal almost overtaking his explosive trademark lung-bursting runs upfield now.

He's going in as the complete full back with the eyes of the continent tracking his movements.

He's one of Everton's best players, he is Ireland's best player and his next step would be the last one. His next step would be to the very top.

But, if we've learned anything over the last 10 years, no-one is better placed to take it. No-one is hungrier for it.

If Seamus Coleman is going to be kept away from home for so long, he's going to make damn sure it was worth his while.

That's where it all started, and that's where it's all leading back to.

Brian Dorrian has already been warned to make sure the St. Catherine's hotseat is clear in time for Coleman to return from his exploits and take charge of his boyhood club with their 100-capacity stand overlooking the pitch.

Seamus Coleman doesn't forget where he's coming from. He doesn't forget the fishing village, the shoreline or the street games. He doesn't forget the GAA or the muddy football fields. It's part of who he is, it's part of the football player he is.

It's the best part of him and he is taking that with him to the summit.

If Seamus Coleman is going to be kept away from home for so long, he's going to make damn sure it was worth his while.

That's where it all started, and that's where it's all leading back to.

Brian Dorrian has already been warned to make sure the St. Catherine's hotseat is clear in time for Coleman to return from his exploits and take charge of his boyhood club with their 100-capacity stand overlooking the pitch.

Seamus Coleman doesn't forget where he's coming from. He doesn't forget the fishing village, the shoreline or the street games. He doesn't forget the GAA or the muddy football fields. It's part of who he is, it's part of the football player he is.

It's the best part of him and he is taking that with him to the summit.

"I know everyone loves where they’re from but I really do love Killybegs. I’m just Seamus who they’ve known playing the Gaelic and kicking a football against the wall on St. Cummins Hill. "There is peace and quiet and family and friends, walks along Fintra Beach and kids on the estate knocking on the door asking me to come outside to play football with them. "No-one treats me like a Premier League footballer."So said the best right back in the world. Brought to you by Three. #MakeHistory

Explore more on these topics: