Share

6th February 2018

11:59am GMT

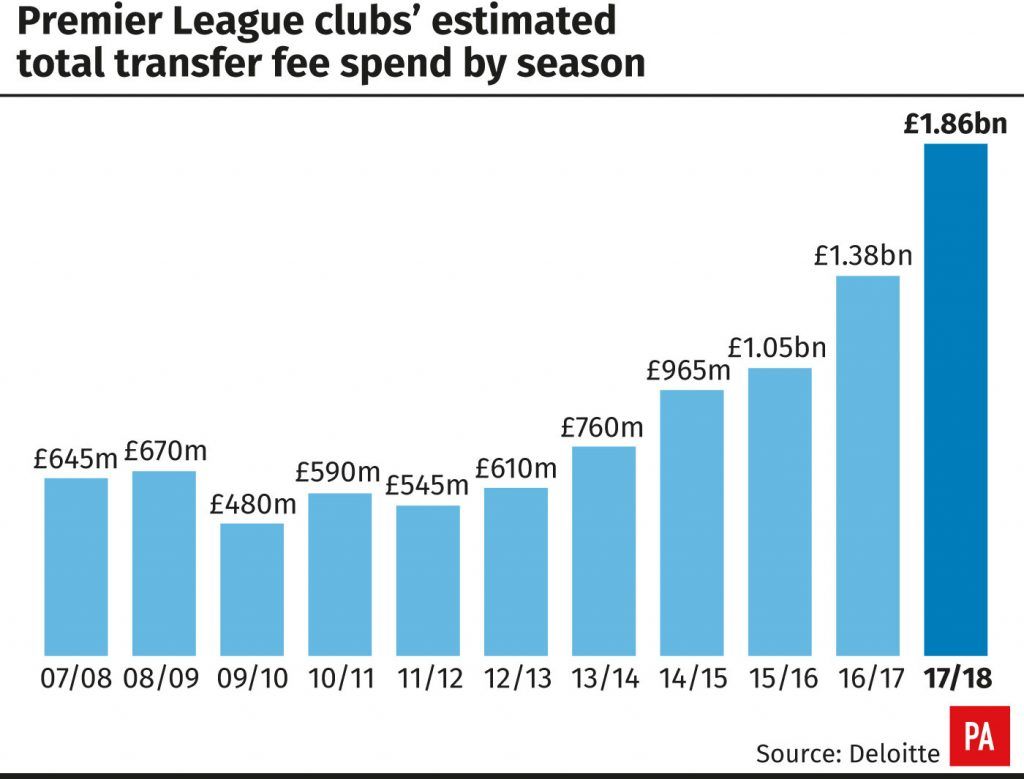

Source: Deloitte/Press Association[/caption]

However, in the recent winter window, nearly two thirds of the gross expenditure was by the top six while the bottom six accounted for about a fifth of the spending.

Arsenal manager Arsene Wenger has keenly observed the money trail, and quite recently made notable contributions towards the figures, but nevertheless feels that the huge increases in football spending has destroyed competition in Europe's biggest leagues.

"When you look at the five big leagues in Europe, in December we already knew four champions," said Wenger.

"That means something is not right in our game. The huge financial power of some clubs is basically destroying the competition."

Source: Deloitte/Press Association[/caption]

However, in the recent winter window, nearly two thirds of the gross expenditure was by the top six while the bottom six accounted for about a fifth of the spending.

Arsenal manager Arsene Wenger has keenly observed the money trail, and quite recently made notable contributions towards the figures, but nevertheless feels that the huge increases in football spending has destroyed competition in Europe's biggest leagues.

"When you look at the five big leagues in Europe, in December we already knew four champions," said Wenger.

"That means something is not right in our game. The huge financial power of some clubs is basically destroying the competition."

Is Wenger right? Has the financial disparity across Europe's top leagues led to predictable, one-sided competitions?

PSG are currently 11 points ahead of Lyon in Ligue 1 and have spent €383 million on players this season compared to Lyon's €63 million.

Manchester City are 13 points ahead of Manchester United in the Premier League and have spent €316 million compared to United's €164 million.

Barcelona are nine points clear of Atletico Madrid in La Liga and have spent €324 million on players compared to Atletico's €102 million, while in the Bundesliga, Bayern sit 18 points ahead of second place Bayer Leverkusen and have out-priced their rivals €116 million to €56 million.

Juventus, who trail Napoli by a single point in the Serie A, are the only glaring anomaly this season after spending €143 million compared to the league leaders' €57 million.

A gulf in spending has directly correlated with a gulf in class.

Bayern Munich have won five consecutive Bundesliga titles. PSG have won four out of the last five titles in Ligue 1, and look primed to reclaim the L'Hexagoal from Monaco this season.

Barcelona and Real Madrid have won 12 of the last 13 La Liga titles, with Atletico Madrid's 2013-14 nothing more than a minor interference in the El Clasico clubs' dominance.

The huge financial increases across Europe's top leagues has definitely led to more one-sided competitions on the continent, that much is clear, but in the Premier League, the most lucrative league in professional football, there have been four different champions over the last five seasons.

Is Wenger right? Has the financial disparity across Europe's top leagues led to predictable, one-sided competitions?

PSG are currently 11 points ahead of Lyon in Ligue 1 and have spent €383 million on players this season compared to Lyon's €63 million.

Manchester City are 13 points ahead of Manchester United in the Premier League and have spent €316 million compared to United's €164 million.

Barcelona are nine points clear of Atletico Madrid in La Liga and have spent €324 million on players compared to Atletico's €102 million, while in the Bundesliga, Bayern sit 18 points ahead of second place Bayer Leverkusen and have out-priced their rivals €116 million to €56 million.

Juventus, who trail Napoli by a single point in the Serie A, are the only glaring anomaly this season after spending €143 million compared to the league leaders' €57 million.

A gulf in spending has directly correlated with a gulf in class.

Bayern Munich have won five consecutive Bundesliga titles. PSG have won four out of the last five titles in Ligue 1, and look primed to reclaim the L'Hexagoal from Monaco this season.

Barcelona and Real Madrid have won 12 of the last 13 La Liga titles, with Atletico Madrid's 2013-14 nothing more than a minor interference in the El Clasico clubs' dominance.

The huge financial increases across Europe's top leagues has definitely led to more one-sided competitions on the continent, that much is clear, but in the Premier League, the most lucrative league in professional football, there have been four different champions over the last five seasons.

The top six Premier League clubs, the clubs that account for two thirds of the league's gross expenditure, occupy six of the top 11 spots in the Deloitte Money League table, a table profiling the highest revenue generating clubs in world football.

The other fives teams - the clubs occupying second, third, fourth, seventh and 10th on the list - three out of five of those teams are currently leading their domestic league, one of those teams, Juventus, trails Napoli by a single point, and the team that occupies second on the list, is none other than back-to-back European champions Real Madrid.

Los Blancos back-to-back Champions League wins are key because if Manchester United had not claimed the Europa League last season, Deloitte predicted that Real Madrid would have retained their status as the highest revenue generating club in world football.

The exposure from a Champions League final can have a monumental financial impact for a club.

In 2016, CNN reported that an estimated 350 million people watched the Champions League final, over twice the amount of people that watched that year's Super Bowl.

Viewing figures for the Champions League and Premier League have taken a hit over the last few seasons as they continue to try and prosper in an ever-challenging media landscape, but the tournament still delivers.

Attendances routinely clear 5 million per season, teams have averaged 2.91 goals from the 2012/13 season to the 2016/17 season, while this year's tournament is on pace for 3.19 goals per match, and in terms of competition, only four clubs - Atletico, Barcelona, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich - have qualified for the quarter-final stages in the last four consecutive tournaments.

However, while an average of 3.19 goals initially looks like it would produce more entertaining games, the number is partly influenced by one-sided thrashing such as Paris Saint-Germain's 5-0 over Celtic, then their 7-1 mauling of the Scottish champions, not to mention their 4-0 win over Anderlecht.

Then there's Chelsea's 6-0 win over Qarabag. Liverpool's 7-0 win over Maribor and 7-0 win over Spartak Moscow. Real Madrid's 6-0 win over APOEL.

The problem has not necessarily been the increased financial investment in football, but rather the widening of the gulf in class that that investment has created.

The money invested by the top 11 clubs has rendered some group stage games completely pointless in terms of competition, but not necessarily in terms of their practicality, as evidenced by Dundalk's Europa League run in 2016.

The League of Ireland club made it to the final round of the 2016/17 Champions League qualifiers, and if they advanced past Legia Warsaw, they would have been placed in the same group as European heavyweights Real Madrid and Borussia Dortmund.

Their 3-1 aggregate defeat to the Polish club denied Stephen Kenny's side unprecedented access to European's football's most high profile competition, but it did however grant the club automatic entry into the Europa League.

Dundalk drew AZ Alkmaar, Zenit St. Petersburg and Maccabi Tel-Aviv in the Europa League group stages, missing out on the likes Manchester United, Roma, Ajax and Inter Milan, but the Louth based did report a €3.3 million profit in the year to the end of November 2016, compared to profits of just under €143,000 during the 2015 financial year.

The top six Premier League clubs, the clubs that account for two thirds of the league's gross expenditure, occupy six of the top 11 spots in the Deloitte Money League table, a table profiling the highest revenue generating clubs in world football.

The other fives teams - the clubs occupying second, third, fourth, seventh and 10th on the list - three out of five of those teams are currently leading their domestic league, one of those teams, Juventus, trails Napoli by a single point, and the team that occupies second on the list, is none other than back-to-back European champions Real Madrid.

Los Blancos back-to-back Champions League wins are key because if Manchester United had not claimed the Europa League last season, Deloitte predicted that Real Madrid would have retained their status as the highest revenue generating club in world football.

The exposure from a Champions League final can have a monumental financial impact for a club.

In 2016, CNN reported that an estimated 350 million people watched the Champions League final, over twice the amount of people that watched that year's Super Bowl.

Viewing figures for the Champions League and Premier League have taken a hit over the last few seasons as they continue to try and prosper in an ever-challenging media landscape, but the tournament still delivers.

Attendances routinely clear 5 million per season, teams have averaged 2.91 goals from the 2012/13 season to the 2016/17 season, while this year's tournament is on pace for 3.19 goals per match, and in terms of competition, only four clubs - Atletico, Barcelona, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich - have qualified for the quarter-final stages in the last four consecutive tournaments.

However, while an average of 3.19 goals initially looks like it would produce more entertaining games, the number is partly influenced by one-sided thrashing such as Paris Saint-Germain's 5-0 over Celtic, then their 7-1 mauling of the Scottish champions, not to mention their 4-0 win over Anderlecht.

Then there's Chelsea's 6-0 win over Qarabag. Liverpool's 7-0 win over Maribor and 7-0 win over Spartak Moscow. Real Madrid's 6-0 win over APOEL.

The problem has not necessarily been the increased financial investment in football, but rather the widening of the gulf in class that that investment has created.

The money invested by the top 11 clubs has rendered some group stage games completely pointless in terms of competition, but not necessarily in terms of their practicality, as evidenced by Dundalk's Europa League run in 2016.

The League of Ireland club made it to the final round of the 2016/17 Champions League qualifiers, and if they advanced past Legia Warsaw, they would have been placed in the same group as European heavyweights Real Madrid and Borussia Dortmund.

Their 3-1 aggregate defeat to the Polish club denied Stephen Kenny's side unprecedented access to European's football's most high profile competition, but it did however grant the club automatic entry into the Europa League.

Dundalk drew AZ Alkmaar, Zenit St. Petersburg and Maccabi Tel-Aviv in the Europa League group stages, missing out on the likes Manchester United, Roma, Ajax and Inter Milan, but the Louth based did report a €3.3 million profit in the year to the end of November 2016, compared to profits of just under €143,000 during the 2015 financial year.

As ever, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. For a club like Dundalk, they can benefit almost immeasurably from qualifying for the group stages of the Europa or Champions League.

For a club like Bournemouth, the riches of the Premier League brought the Cherries from the brink of administration in 2008 to the 28th richest club in world football in 2018.

But at the top end, in four out of five of Europe's top leagues, the competition has become predictable and aligns directly with the money league table in that the world's highest revenue earners are the same clubs that are dominating their domestic leagues and obliterating smaller clubs in the Champions League.

The knockout stages of that tournament are a lot less predictable, but even if only four clubs have qualified for the quarter-finals stages in the last four seasons, the same number of clubs - Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico and Juventus - have contested the last four Champions League finals.

Money may have ruined football if you don't support one of the world's top 11 richest clubs, and if you do support one of those clubs, the possibilities are in some cases limitless as to what players you can sign.

If you like watching a select number of clubs cherry pick from the world's best players and dominate their domestic league and the Champions League, the financial growth of European football has undoubtedly bettered football, but if you find each league painfully predictable, then maybe sizable financial spending has been for the worse, although AC Milan and Lyon are perfect examples of teams that dominated their domestic league without the financial muscle of some of modern football's elite clubs.

Money trickles down from the top to the bottom but just because those at the top of European football appear to be the only members eating at the table, doesn't mean those at the bottom aren't benefiting twenty-fold from their crumbs.

As ever, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. For a club like Dundalk, they can benefit almost immeasurably from qualifying for the group stages of the Europa or Champions League.

For a club like Bournemouth, the riches of the Premier League brought the Cherries from the brink of administration in 2008 to the 28th richest club in world football in 2018.

But at the top end, in four out of five of Europe's top leagues, the competition has become predictable and aligns directly with the money league table in that the world's highest revenue earners are the same clubs that are dominating their domestic leagues and obliterating smaller clubs in the Champions League.

The knockout stages of that tournament are a lot less predictable, but even if only four clubs have qualified for the quarter-finals stages in the last four seasons, the same number of clubs - Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico and Juventus - have contested the last four Champions League finals.

Money may have ruined football if you don't support one of the world's top 11 richest clubs, and if you do support one of those clubs, the possibilities are in some cases limitless as to what players you can sign.

If you like watching a select number of clubs cherry pick from the world's best players and dominate their domestic league and the Champions League, the financial growth of European football has undoubtedly bettered football, but if you find each league painfully predictable, then maybe sizable financial spending has been for the worse, although AC Milan and Lyon are perfect examples of teams that dominated their domestic league without the financial muscle of some of modern football's elite clubs.

Money trickles down from the top to the bottom but just because those at the top of European football appear to be the only members eating at the table, doesn't mean those at the bottom aren't benefiting twenty-fold from their crumbs.

Explore more on these topics: