Share

19th November 2019

11:57am GMT

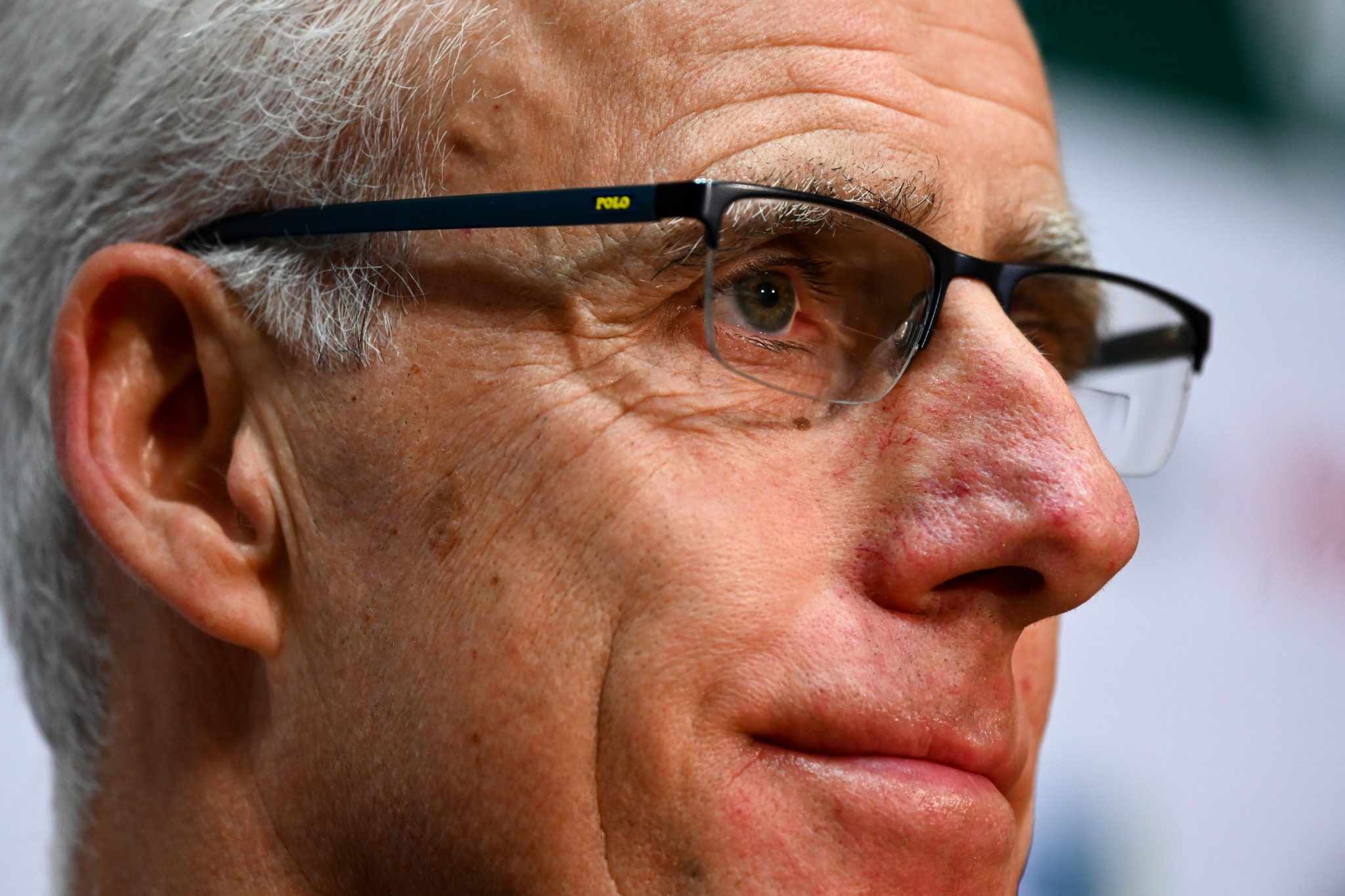

It's like the difference between Roy Keane and David Moyes giving you an answer. You often don't listen to the question until the person it's directed at gets chippy with it. You could ask David Moyes how he feels after his team conceded a last-minute goal that beat them and he'll politely give you an answer to fill your ink inches with quotes. Ask Roy Keane the same question and he'd probably snap back asking how the fuck do you think he's feeling. And then you'd have boys outside the presser agreeing that it was a stupid question.

A lot of the time, they're just prompts to keep the manager talking and one of the first ones lobbed up for Mick after the draw - another draw - with Denmark stroked his ego by mentioning how well the team played. But, you know, despite how absolutely amazingly you had your lads performing, "was it just a case of not being clinical enough in front of goal?"

It's like the difference between Roy Keane and David Moyes giving you an answer. You often don't listen to the question until the person it's directed at gets chippy with it. You could ask David Moyes how he feels after his team conceded a last-minute goal that beat them and he'll politely give you an answer to fill your ink inches with quotes. Ask Roy Keane the same question and he'd probably snap back asking how the fuck do you think he's feeling. And then you'd have boys outside the presser agreeing that it was a stupid question.

A lot of the time, they're just prompts to keep the manager talking and one of the first ones lobbed up for Mick after the draw - another draw - with Denmark stroked his ego by mentioning how well the team played. But, you know, despite how absolutely amazingly you had your lads performing, "was it just a case of not being clinical enough in front of goal?"

"Well, obviously we weren't," McCarthy had both his arms out as if to gesture what on earth you're asking that for. "I think that answers that."The tone was set. On one occasion, he took exception to someone sympathising with his situation for having to use a sub at half time. John Egan had to come off and Ciaran Clark replaced him - and this wasn't so much a question from the journalist as it was just a statement of empathy about the manager having his hands tied with but two subs left for the rest of the game; therefore running out of options to change the thing in an attacking sense when Ireland went behind later on. "Behave yourself," Mick cut him off. The manager seemed to think the angle was basically that he didn't have enough balls to put on a more advanced player for Egan. He pointed out that he was a centre half. He reminded the journalist that the substitution was at half time but it took three occasions for the message to get back that he wasn't picking holes in the decisions, just observing that it resulted in less flexibility for the manager. "I had a centre half injured and I replaced him with a centre half," it wasn't a night for cosying up with him. But what McCarthy said after that was telling of his mindset going into the match.

"It was 0-0 and I wanted to get it as long as I possibly could."In the last month, there's been this constant reminder of how your hand would've been bitten off at the start of the campaign had you offered Mick the chance to qualify for the Euros with one home match at the end. This was Ireland's best performance but the team selection and that insight from the manager suggested that the thinking in the changing room pre-game was that he'd bite your hand off to have it at 0-0 with 15 minutes to go, needing just one goal to qualify. Here's the thing: it's really hard to score a goal. Another manager might use that as motivation to use every minute you can to try and score but for some, it's even more important to not concede because you don't want to leave yourself with the task of having to score two. So McCarthy apparently wants to get through the game for as long as he can at 0-0 and the thinking is that it simplifies the task - score one goal and go for it for a shorter period where it's less likely that they'll punish you for opening up. But it's also less likely you'll score with less time.

The fundamental principle though is to make sure you only have one goal to score. To do that, you have to make sure they don't score. To do that, you have to play the guys you can trust to do that dog work.

Jeff Hendrick didn't offer much on the ball for Ireland on Monday night. One or two touches and it was gone, usually back in the same direction it came from. It might be a confidence thing or an instruction but he's not turning on the ball as much as the side's most advanced midfielder should be. It's obvious he's not at the heights he hit at Euro 2016 but that's not because things aren't coming off for him, it's because he's not trying them anymore.

McCarthy was asked about Hendrick playing virtually as a striker against Denmark and he gave the usual before honing in on what he does from a defensive point of view.

The fundamental principle though is to make sure you only have one goal to score. To do that, you have to make sure they don't score. To do that, you have to play the guys you can trust to do that dog work.

Jeff Hendrick didn't offer much on the ball for Ireland on Monday night. One or two touches and it was gone, usually back in the same direction it came from. It might be a confidence thing or an instruction but he's not turning on the ball as much as the side's most advanced midfielder should be. It's obvious he's not at the heights he hit at Euro 2016 but that's not because things aren't coming off for him, it's because he's not trying them anymore.

McCarthy was asked about Hendrick playing virtually as a striker against Denmark and he gave the usual before honing in on what he does from a defensive point of view.

"He's got the capability to do that (play so far forward) because he's good with the ball, he can find the pass and he's got the legs to run in behind as well. "He also did a great job with Didzi [McGoldrick] of stopping them playing through the middle of us."McCarthy compared it to the 5-1 last year and credits Ireland's two most attacking players for playing key roles in stopping a repeat of that, despite the only ingredient that day being Ireland emerging in the second half with no midfield. Hendrick is good with the ball - at least he has been in the past - and he can find a pass but he didn't show that in the must-win match on Monday and he hasn't shown it for a while, but you have to wonder if McCarthy actually cares that much about that. When your mentality is always to keep it at 0-0 for as long as you can and try to nick it, what the team does on the ball becomes more and more immaterial. Managers like that, like O'Neill looked to move more towards, assume the worst in the players' abilities on the ball, they assume the best in the opposition and they assume that they're going to struggle to score all the time so their interest only really peaks when the other team is attacking. That's when the panic sets in and that's when you want to make damn sure there's no way through for them because, as long as it's 0-0, anything can happen for you still. So you look up quickly to see if everything's alright at the back and your trusted lieutenants are already in position. Whelan is there, set up. Hendrick is there, strong and fit. The team is ready because your comfort blanket is in place. And you relax a little because they've stuck to their jobs and they've set the defence up like you've wanted to. It might be basic but not everyone does that. They don't have the discipline or the cop on to religiously follow that for 90 minutes and they don't have the sense to know when to go or stay. At one point, McCarthy looked to be going crazy shouting at Alan Browne to push out and apply pressure on the wing as Denmark tentatively entered Ireland's half. Whelan arrived and kind of nudged Browne out of his way, pressed the ball, encouraged McGoldrick to join him from the other side and the manager banged his hands together in admiration as the Danes were forced back into defence.

It sounds simple, we'd all do it if we were offered the chance to do it for our country, but, no - not every player does it. Either they can't or they don't but they drift, they switch off, they get lazy.

Whelan doesn't get lazy. Hendrick doesn't switch off.

McCarthy talked about how it's experience you need for these games, that it always has been - it seemed like a dig at the clamours for youth and the cries for Jack Byrne. It's not clear though if he's really after experience or just the guys who have the experience of knowing where to be when Ireland don't have the ball.

Alan Browne and Jeff Hendrick were both playing relatively out of position and one at a time was acting as the second striker. Watching, it didn't make sense that Ireland just wouldn't play a second attacker instead - like Robinson or Maguire or Parrott or, most pertinently, like Jack Byrne.

If Byrne had come on last night it would've lifted the roof off the place and he doesn't need experience to have that affect on people. Fans would've gotten excited knowing that he was going to start controlling things. He would've demanded the ball, he would've turned his body, picked passes and went again. He'd be pulling the team forward and knitting things more in the final third where it was mostly just crosses that were getting supporters roused. That and lung-bursting runs back into defence.

It sounds simple, we'd all do it if we were offered the chance to do it for our country, but, no - not every player does it. Either they can't or they don't but they drift, they switch off, they get lazy.

Whelan doesn't get lazy. Hendrick doesn't switch off.

McCarthy talked about how it's experience you need for these games, that it always has been - it seemed like a dig at the clamours for youth and the cries for Jack Byrne. It's not clear though if he's really after experience or just the guys who have the experience of knowing where to be when Ireland don't have the ball.

Alan Browne and Jeff Hendrick were both playing relatively out of position and one at a time was acting as the second striker. Watching, it didn't make sense that Ireland just wouldn't play a second attacker instead - like Robinson or Maguire or Parrott or, most pertinently, like Jack Byrne.

If Byrne had come on last night it would've lifted the roof off the place and he doesn't need experience to have that affect on people. Fans would've gotten excited knowing that he was going to start controlling things. He would've demanded the ball, he would've turned his body, picked passes and went again. He'd be pulling the team forward and knitting things more in the final third where it was mostly just crosses that were getting supporters roused. That and lung-bursting runs back into defence.

Irish fans don't ask for much. In fact, they're so conditioned to think nothing will come from open play that there were groans when Hourihane went short with a corner to Enda Stevens in a move that resulted in him almost scoring with a mouthwatering in-swinging cross in the second half.

The thing that had everyone off their feet the longest was to check what side of the corner flag the ball was going to roll out past late on. When it went for a throw, the enthusiasm drained because there was no chance to land it on someone's head - no chance for a defender to score, more like.

Imagine the stadium if there was an extra player attacking. Imagine if there was a creative midfielder trying to methodically take the team up the pitch and push runners ahead of him.

You wouldn't have given up anything by playing Jack Byrne instead of someone like Hendrick on the night. You could only have gained something by doing that because there was enough cover as it was and, frankly, there's not enough troubling factors in the Denmark team anyway.

But it's not that Byrne or any of these guys are inexperienced. It's that McCarthy and so many successful managers trust more the guys who do as they're told.

The tactic was to keep it scoreless for as long as possible and then go for it. Having seen one half of that model break down, Ireland switched into going for it and they went for it alright, so much so that white jerseys were falling over themselves trying to keep them out. It was a good performance but, unfortunately, they only sincerely went for the jugular when they needed two goals and when the clock was running down.

If they had been trying to score for longer, it would've served them better.

That might mean giving up one of the boys who do exactly as they're told. Sometimes, though, you can tell footballers to do things in the other direction too.

Irish fans don't ask for much. In fact, they're so conditioned to think nothing will come from open play that there were groans when Hourihane went short with a corner to Enda Stevens in a move that resulted in him almost scoring with a mouthwatering in-swinging cross in the second half.

The thing that had everyone off their feet the longest was to check what side of the corner flag the ball was going to roll out past late on. When it went for a throw, the enthusiasm drained because there was no chance to land it on someone's head - no chance for a defender to score, more like.

Imagine the stadium if there was an extra player attacking. Imagine if there was a creative midfielder trying to methodically take the team up the pitch and push runners ahead of him.

You wouldn't have given up anything by playing Jack Byrne instead of someone like Hendrick on the night. You could only have gained something by doing that because there was enough cover as it was and, frankly, there's not enough troubling factors in the Denmark team anyway.

But it's not that Byrne or any of these guys are inexperienced. It's that McCarthy and so many successful managers trust more the guys who do as they're told.

The tactic was to keep it scoreless for as long as possible and then go for it. Having seen one half of that model break down, Ireland switched into going for it and they went for it alright, so much so that white jerseys were falling over themselves trying to keep them out. It was a good performance but, unfortunately, they only sincerely went for the jugular when they needed two goals and when the clock was running down.

If they had been trying to score for longer, it would've served them better.

That might mean giving up one of the boys who do exactly as they're told. Sometimes, though, you can tell footballers to do things in the other direction too.Explore more on these topics: