Share

24th May 2017

04:47pm BST

Any heated conversation I had was shaped around the Derry team. We started trekking to random club games to see if anyone else was out there to help our county's cause.

I soon signed up with my own local club and spent every single age group the whole way through to seniors battling just to keep hold of a starting jersey. Some days I won, some days I lost, but I went away in the intervening weeks and plotted victory all over again. I lost myself completely and utterly in this struggle because it was easier to focus my energy on that. For months, it seemed like my family had expended all its effort not even muttering a word about what happened so, after a while, my biggest protection was avoidance.

It was safer being out and away from it all than facing the grim subtext of a silent house when something like a fence or a sink had broken and no-one was able to fix it.

It was easier to talk about the club team and the work I was going to do to get the jersey back when you realised that, after a year, no-one was going to address the missing plate at dinner.

In time though, the laughing and wisdom that came from the head of family was replaced with me and my brother's own laughter from stories on the road, from arguments about the Derry team, from exaggerated impersonations of the once-strange distant relative who became one of the most important people in my life.

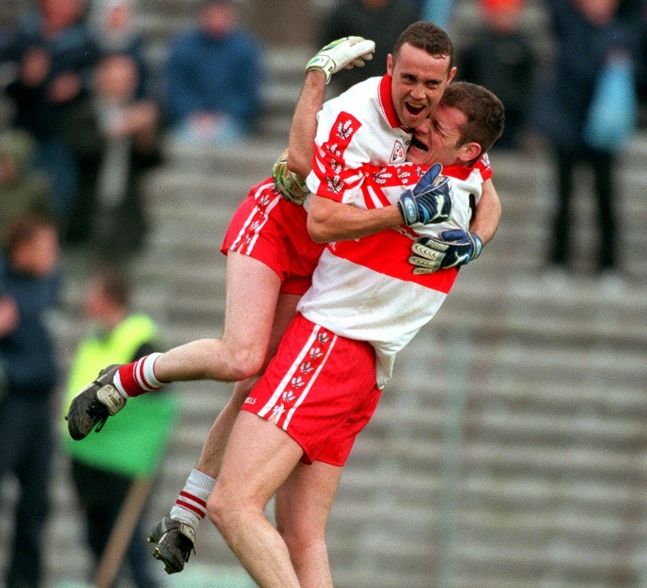

Because, by the time I had grown up, I was consumed by this way of life. My purpose seemed solely to honour the greater good of the empire of my club and my county. From coaching underage teams to bitching about the senior side and eulogising about Derry players, my world became filled by what many would think inconsequential entities but, to me, they were all glorious relief that you could spend a lifetime content with.

Any heated conversation I had was shaped around the Derry team. We started trekking to random club games to see if anyone else was out there to help our county's cause.

I soon signed up with my own local club and spent every single age group the whole way through to seniors battling just to keep hold of a starting jersey. Some days I won, some days I lost, but I went away in the intervening weeks and plotted victory all over again. I lost myself completely and utterly in this struggle because it was easier to focus my energy on that. For months, it seemed like my family had expended all its effort not even muttering a word about what happened so, after a while, my biggest protection was avoidance.

It was safer being out and away from it all than facing the grim subtext of a silent house when something like a fence or a sink had broken and no-one was able to fix it.

It was easier to talk about the club team and the work I was going to do to get the jersey back when you realised that, after a year, no-one was going to address the missing plate at dinner.

In time though, the laughing and wisdom that came from the head of family was replaced with me and my brother's own laughter from stories on the road, from arguments about the Derry team, from exaggerated impersonations of the once-strange distant relative who became one of the most important people in my life.

Because, by the time I had grown up, I was consumed by this way of life. My purpose seemed solely to honour the greater good of the empire of my club and my county. From coaching underage teams to bitching about the senior side and eulogising about Derry players, my world became filled by what many would think inconsequential entities but, to me, they were all glorious relief that you could spend a lifetime content with.

And through the years, you don't even remember when it got better. You don't realise when it was that you were no longer doing this as an escape but that it was just part of who you are. You don't appreciate how long it took for anyone in your family to say aloud the two syllables that make up the word "daddy" because it used to choke you up and it used to never get said.

As Ken Early put it so perfectly in the Irish Times, it is fantasy. But it helped.

And through the years, you don't even remember when it got better. You don't realise when it was that you were no longer doing this as an escape but that it was just part of who you are. You don't appreciate how long it took for anyone in your family to say aloud the two syllables that make up the word "daddy" because it used to choke you up and it used to never get said.

As Ken Early put it so perfectly in the Irish Times, it is fantasy. But it helped.

"George Orwell was never more wrong than when he wrote that serious sport was 'war minus the shooting'. "The truth is that sport is the opposite of war: it unfolds according to rules that everyone understands. To care about sport, to allow yourself to be emotionally invested in what happens when 22 people kick a ball around for 90 minutes, is obviously to step into a fantasy world."Now, these things aren't just my passion and my distraction, they're my livelihood. And there's something so wonderful about being able to throw yourself into sport as if it's the be all and end all. As if it is really important. Because, make no mistake about it, at its best, sport has the ability to propel people. It has the ability to unite, to inspire and to make you believe that anything is possible. It's a place you take out your life's frustrations, like a permanent, sturdy punch bag that's always there for you. It's somewhere you can allow yourself to become completely lost in and completely broken by, safe in the knowledge that you can step away any time you want. For a lot of this planet, sport gives them a reason to live - even if it's only pantomime at the end of it all. Even if it's only to escape real life. In a week like this that's just past though, you get dragged into harsh reality swiftly again and it's hard to get back. It's hard to get back into the bubble where you can pretend like passages of play are important. It's hard to get back into the mindset of arguing wildly about the performances and results of Jose Mourinho's Manchester United. The Europa League final represents a small opportunity to do that once more. Call it ignorant, call it naive, you can even call it insensitive if you want but, for 90 minutes at least, it will be a better world pretending like this game actually matters. For another 90 minutes, it will be a glorious relief to get lost in the fantasy again.

Explore more on these topics: