Share

26th May 2016

05:48pm BST

Could he offer a guiding hand for the players who are in that position in 2016? Would be able to offer some words of consolation if they weren’t in the 23 when Martin O’Neill makes his final decision on Tuesday?

The answer was typical of O’Shea: reasonable, self-effacing and unobtrusive.

“I hadn’t even come to train or meet up with the squad. It wasn’t as if I got even close to going,” he said as he recalled that time.

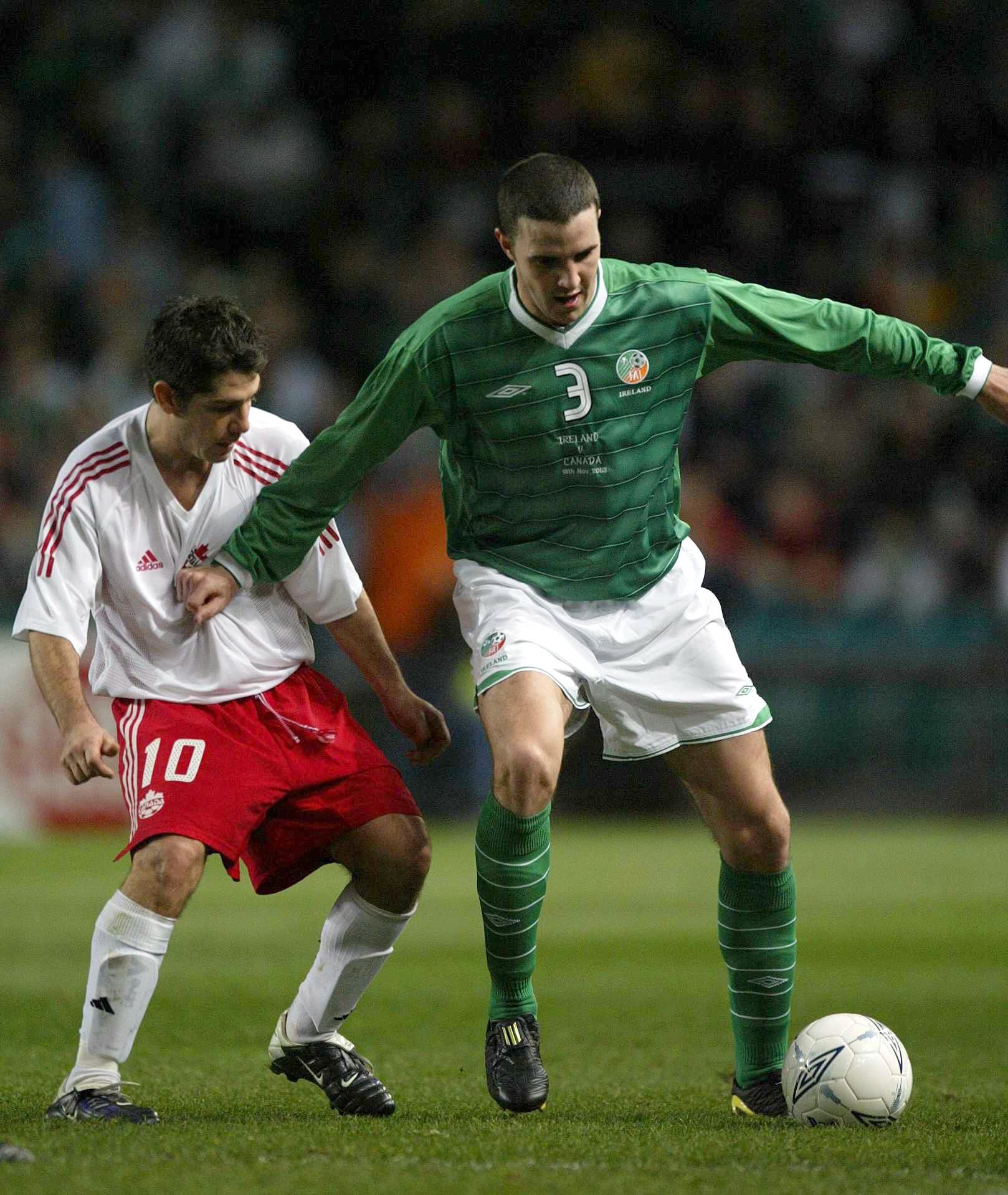

The most startling thing was the realisation that nearly 15 years have passed since O’Shea made his international debut against Croatia. He missed out on the 2002 World Cup, but the following year he made his breakthrough for Manchester United and he has been a constant presence for Ireland ever since.

And his presence in the squad is as important as his contribution on the field. There have been times when he may have struggled on the pitch, but an international squad needs players like O’Shea and Robbie Keane to provide a sense of permanence and calm.

He lost his place in the Sunderland side after injury this season as they put together their run which saved them for relegation, but Sam Allardyce praised O'Shea's qualities and has predicted a career in management for him.

O’Shea always seemed to have that sense of calm and perspective. I remember interviewing him in his early years at United. He had agreed to meet in a hotel in Manchester, but then rang to say he was running late.

When he finally showed up, he was full of apologies, explaining that he was getting into his car to drive into town when he noticed there was a nail in the car’s tyre. Some footballers might have decided that they’d done their best to meet the reporter at that stage and cancelled citing an unavoidable act of God. Others would simply have decided not to show up at all. Instead O’Shea jumped on a tram and headed into Manchester.

Some lose the naivety or innocence and think behaving normally was somehow a symptom of these conditions, but O’Shea was never naive or innocent. Instead he just had a sceptical view of bullshit. It may seem like faint praise to credit a player for getting on a tram, but in a world where many can see nothing but the craziness, it should always be noted at least.

He was a gifted player growing up in Ferrybank and all the clubs came to look at him. Those who played against him noticed a calm and assured presence on the field, and then they noticed the bunch of scouts watching him on the sideline.

Liverpool and Celtic were interested. He had a week in London with QPR. They offered a contract but O’Shea decided to get a good Leaving Cert and then go to England. He knew they’d be back, but maybe he also knew not to take it all too seriously, not to get carried away with the bullshit.

He got a good Leaving Cert all right and then he went and signed for Manchester United.

Some might say that the self-effacement held him back when he went away, that there were times when he became too easily identifiable as a utility player at United, and he would have been better off being less agreeable.

Others would call bullshit on that. They’d make the case with some justification that he made it at Manchester United like very few make it. He won titles and picked up a Champions League medal. He lost nothing through a scepticism of the bullshit.

In that breakthrough season at Old Trafford, he was nominated for the PFA Young Player of the Year award as United chased Arsenal down and claimed another title.

Anything seemed possible for O’Shea then and yet his achievements are somewhat unfairly overlooked.

Last summer, O’Neill and O’Shea faced the press the day before Ireland played England. It was also the day of the Champions League final so O’Neill was asked his memories of winning the European Cup with Nottingham Forest.

There wasn’t as much interest in the Champions League memories of the man sitting beside him who had been part of a squad that won it in 2008, and who had started in the final the following year when United lost to Barcelona.

There are moments that stand out. It seemed almost out of character that he marked his hundredth cap with the equaliser against Germany in Gelsenkirchen. It was almost too demanding of the spotlight for a player who handles it easily, but never gets carried away with the fuss. The following weekend, as if offering a reminder of the dangers of getting carried away, Sunderland lost 8-0.

On Thursday, he didn’t want to talk about retirement. It wouldn’t be O’Shea’s way to announce that this tournament will be his last. Or that he planned to go on and on. It would be good for Ireland if he did and typical of John O'Shea to make no fuss about it.

Explore more on these topics: