Share

4th April 2016

06:13pm BST

One man found that increasingly he couldn’t do without the doctor’s injections. That man was the president of the United States, John F Kennedy.

“I don’t care if it’s horse piss, it’s the only thing that works,” JFK was reported to have said about the doctor’s cocktails.

If Max Jacobson - also known as Dr Feelgood - had ever been exposed in a secret film boasting of his connections to the White House, it would have been easy to dismiss him as an unreliable and eccentric quack, mainly because he was an unreliable and eccentric quack.

When the name of Dr Mark Bonar was released on Saturday night ahead of the Sunday Times story, a quick Google search demonstrated that he might be the kind of man who would exaggerate his connections in the world of sport to entice a client to sign up to his methods.

One man found that increasingly he couldn’t do without the doctor’s injections. That man was the president of the United States, John F Kennedy.

“I don’t care if it’s horse piss, it’s the only thing that works,” JFK was reported to have said about the doctor’s cocktails.

If Max Jacobson - also known as Dr Feelgood - had ever been exposed in a secret film boasting of his connections to the White House, it would have been easy to dismiss him as an unreliable and eccentric quack, mainly because he was an unreliable and eccentric quack.

When the name of Dr Mark Bonar was released on Saturday night ahead of the Sunday Times story, a quick Google search demonstrated that he might be the kind of man who would exaggerate his connections in the world of sport to entice a client to sign up to his methods.

He was also the kind of man who could easily be doing all that he claimed in the film secretly made by the Sunday Times.

Bonar claimed to have worked with 150 sportspeople, including players at Arsenal, Chelsea and Leicester City. The Sunday Times said they had no “independent evidence Bonar treated the players” and all the clubs denied his claims. On Sunday, Bonar described the Sunday Times story as “false and very misleading”.

Bonar may turn out to be another Walter Mitty, albeit a Walter Mitty who considered standing for UKIP, but the reality of doping is that when the story breaks in football, it is more likely to be a character like Bonar who reveals more than he intends than someone whose credentials are impeccable.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/716543023400751104

This is often the truth of doping in sport. Dr Michele Ferrari, the doctor most closely associated with Lance Armstrong, said EPO was no more dangerous than ten litres of orange juice.

Eufemiano Fuentes – the doctor at the centre of Operation Puerto, the Spanish investigation into doping in sport – once flew out to a time trial during the Tour of Spain with a small fridge in the seat beside him. “Here lies the key to the Vuelta,” he told reporters.

Dr Luis Garcia del Moral was said to have “regularly fabricated” prescriptions for corticosteroids and injected cyclists with EPO. He was banned from sport for life by USADA for his connections to Lance Armstrong. Del Moral claimed he was a “medical adviser’ to Barcelona and Valencia.

In 2012, Barcelona denied that Del Moral was ever on the payroll at the club, but told the Daily Telegraph “they could not guarantee that Del Moral had not been engaged on an ad hoc basis by the medical department during that period, or been used by individual players. They added that there has since been an overhaul of the club’s medical system and personnel”.

All these men had their eccentricities but that didn’t prevent them becoming key figures in various doping operations.

Currently without a licence to practise in the UK, Bonar is the kind of figure it is easy to dismiss.

When Leicester’s manager Claudio Ranieri was asked about the doping allegations following the league leaders’ win over Southampton on Sunday, the club’s press officer referred reporters to the club’s statement earlier that day which had vehemently denied the claims.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BQYAZt0Ij4c

Bonar also introduced the Sunday Times undercover team to Rob Brinded, who had worked as head of strength, conditioning and injury at Chelsea from 2001 to 2007 and went on to become a fitness coach in Barcelona.

Bonar said he and Brinded had “collaborated” on a lot of clients in the past five or six years, long after he left Chelsea. “I know he’s worked with a lot of footballers,” Brinded was recorded saying on film.

Brinded had told the undercover reporter from the Sunday Times that he was “neutral” regarding performance enhancing drugs but also said that side of the operation would be handled by Bonar.

He was also the kind of man who could easily be doing all that he claimed in the film secretly made by the Sunday Times.

Bonar claimed to have worked with 150 sportspeople, including players at Arsenal, Chelsea and Leicester City. The Sunday Times said they had no “independent evidence Bonar treated the players” and all the clubs denied his claims. On Sunday, Bonar described the Sunday Times story as “false and very misleading”.

Bonar may turn out to be another Walter Mitty, albeit a Walter Mitty who considered standing for UKIP, but the reality of doping is that when the story breaks in football, it is more likely to be a character like Bonar who reveals more than he intends than someone whose credentials are impeccable.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/716543023400751104

This is often the truth of doping in sport. Dr Michele Ferrari, the doctor most closely associated with Lance Armstrong, said EPO was no more dangerous than ten litres of orange juice.

Eufemiano Fuentes – the doctor at the centre of Operation Puerto, the Spanish investigation into doping in sport – once flew out to a time trial during the Tour of Spain with a small fridge in the seat beside him. “Here lies the key to the Vuelta,” he told reporters.

Dr Luis Garcia del Moral was said to have “regularly fabricated” prescriptions for corticosteroids and injected cyclists with EPO. He was banned from sport for life by USADA for his connections to Lance Armstrong. Del Moral claimed he was a “medical adviser’ to Barcelona and Valencia.

In 2012, Barcelona denied that Del Moral was ever on the payroll at the club, but told the Daily Telegraph “they could not guarantee that Del Moral had not been engaged on an ad hoc basis by the medical department during that period, or been used by individual players. They added that there has since been an overhaul of the club’s medical system and personnel”.

All these men had their eccentricities but that didn’t prevent them becoming key figures in various doping operations.

Currently without a licence to practise in the UK, Bonar is the kind of figure it is easy to dismiss.

When Leicester’s manager Claudio Ranieri was asked about the doping allegations following the league leaders’ win over Southampton on Sunday, the club’s press officer referred reporters to the club’s statement earlier that day which had vehemently denied the claims.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BQYAZt0Ij4c

Bonar also introduced the Sunday Times undercover team to Rob Brinded, who had worked as head of strength, conditioning and injury at Chelsea from 2001 to 2007 and went on to become a fitness coach in Barcelona.

Bonar said he and Brinded had “collaborated” on a lot of clients in the past five or six years, long after he left Chelsea. “I know he’s worked with a lot of footballers,” Brinded was recorded saying on film.

Brinded had told the undercover reporter from the Sunday Times that he was “neutral” regarding performance enhancing drugs but also said that side of the operation would be handled by Bonar.

He revealed to the Sunday Times that he had been told that a number of Chelsea players had been taking performance enhancing drugs during his years at the club.

Over the weekend, Brinded’s lawyer said there must have been a misunderstanding and he denied saying that any Chelsea player was taking banned drugs. The Sunday Times pointed out that there was no evidence the sportspeople Bonar claimed to have treated were referred to him by Brinded.

"The claims the Sunday Times put to us are false and entirely without foundation," Chelsea said in a statement. "Chelsea Football Club has never used the services of Dr Bonar and has no knowledge or record of any of our players having been treated by him or using his services."

Brinded denied working or collaborating with Bonar and said he had never referred any athletes to him. “To the best of my knowledge, none of my clients, athletes or otherwise take performance enhancing drugs,” he told the Sunday Times.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/717013616562728961

Bonar and Brinded’s connection doesn’t prove anything, but it does have the potential to elevate the story to something other than the ramblings of a fantasist.

Brinded, of course, could have been fantasising or merely speculating when he was filmed saying he knew Bonar worked with a lot of footballers.

For those who say there has been little talk of doping from within the game, Bonar’s story was underwhelming. He was a disgraced and ludicrous figure whose claims could easily be dismissed.

The problem is that when the talk comes from impeccable figures within the game, nobody pays much attention either.

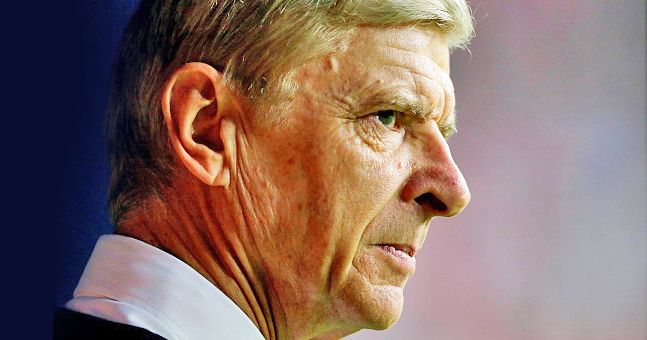

“We have had some players come to us at Arsenal from other clubs abroad and their red blood cell count has been abnormally high. That kind of thing makes you wonder," Arsene Wenger said in 2004.

He revealed to the Sunday Times that he had been told that a number of Chelsea players had been taking performance enhancing drugs during his years at the club.

Over the weekend, Brinded’s lawyer said there must have been a misunderstanding and he denied saying that any Chelsea player was taking banned drugs. The Sunday Times pointed out that there was no evidence the sportspeople Bonar claimed to have treated were referred to him by Brinded.

"The claims the Sunday Times put to us are false and entirely without foundation," Chelsea said in a statement. "Chelsea Football Club has never used the services of Dr Bonar and has no knowledge or record of any of our players having been treated by him or using his services."

Brinded denied working or collaborating with Bonar and said he had never referred any athletes to him. “To the best of my knowledge, none of my clients, athletes or otherwise take performance enhancing drugs,” he told the Sunday Times.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/717013616562728961

Bonar and Brinded’s connection doesn’t prove anything, but it does have the potential to elevate the story to something other than the ramblings of a fantasist.

Brinded, of course, could have been fantasising or merely speculating when he was filmed saying he knew Bonar worked with a lot of footballers.

For those who say there has been little talk of doping from within the game, Bonar’s story was underwhelming. He was a disgraced and ludicrous figure whose claims could easily be dismissed.

The problem is that when the talk comes from impeccable figures within the game, nobody pays much attention either.

“We have had some players come to us at Arsenal from other clubs abroad and their red blood cell count has been abnormally high. That kind of thing makes you wonder," Arsene Wenger said in 2004.

Earlier this season, Wenger (above) said football had a doping problem. After a Dinamo Zagreb player failed a drugs test following a game against Arsenal, Wenger claimed that Uefa’s regulations “basically accept doping”. Uefa’s response was swift and ten testers subsequently showed up at Arsenal’s training ground.

Mark Bonar and Arsene Wenger don’t seem to have many shared values. One is a rogue doctor and the other is one of the greatest figures in the history of football. But they do have one thing in common: when they talk about doping in the game, nobody wants to listen to what they say.

Earlier this season, Wenger (above) said football had a doping problem. After a Dinamo Zagreb player failed a drugs test following a game against Arsenal, Wenger claimed that Uefa’s regulations “basically accept doping”. Uefa’s response was swift and ten testers subsequently showed up at Arsenal’s training ground.

Mark Bonar and Arsene Wenger don’t seem to have many shared values. One is a rogue doctor and the other is one of the greatest figures in the history of football. But they do have one thing in common: when they talk about doping in the game, nobody wants to listen to what they say.Explore more on these topics: