Share

25th June 2017

12:37pm BST

He said how much he had enjoyed being there and what a wonderful day it had been.

They moved on to a more general cricket conversation and when they’d stopped, I asked the man about the day at Lord’s.

It turned out his son had been playing for Ireland on that historic day, and that the man he had been talking to at lunch played cricket with his son.

It had all been so magical, he said. There was pride in watching his son play cricket for Ireland at Lord’s, of course. And there was also something else. He had seen so many people he knew from the world of Irish cricket as he wandered around headquarters. He made it sound glorious to have been there to watch Ireland play - and play competitively - on this hallowed ground. This was a shared experience, another important step taken by the Irish cricket community on an incredible journey.

When Ireland beat Pakistan in 2007 and England in 2011, the country took notice and the game grew. When they beat the West Indies in 2015, it was another tremendous achievement, even if it was a victory they believed was possible against a fading giant of the game.

Now Ireland, along with Afghanistan, have become full members of the ICC and they may play a Test against England at Lord’s in 2019, something which would be another beautiful gathering for the people who have supported and loved the game in the country.

On Thursday, in our brief conversation, we talked about the ICC council meeting. He expressed some concerns about the situation. So much of it was driven by politics so you could never be sure how those things would turn out, he said.

I asked him at what age my son who is three (with two cricket obsessives as grandfathers - one from Abbottabad, the other from Tralee - we have high hopes) could start playing and he said he could probably come along to his club any time he liked. We moved on to some other subject and he went on his way, while I felt my day had been enhanced by this random encounter.

When the ICC announced later that day that Ireland would indeed become a Test nation, the chance meeting seemed fitting. The man and his son were part of the Irish cricket community which had sustained the game and helped it reach this position. Ed Joyce and four of his siblings have played cricket for Ireland. Niall and Kevin O’Brien were there on the historic days and the less than historic days, while their father Brendan also played cricket for Ireland.

These were the people who kept the game going when it was seen as alien by some and elitist by those who never explored its roots, in Ireland or around the world.

The wonderful documentary Batmen told the real story of Irish cricket, reminding people that it was the country’s most popular sport in the 19th century and that there was a particular presence in counties where hurling would one day be strong.

Some of the reports of Ireland’s achievement felt obliged to talk about cricket as if they were explaining the rules of Kabaddi to an audience which had never watched the game before. The truth is different. The audience is growing, thanks to the popularity of Twenty20 on television and the enjoyment that comes from playing the game at any level and at any age.

The achievement has been driven by the most able sporting administrator in Ireland, Warren Deutrom who made it his mission to achieve Test status by 2020.

On Thursday lunchtime, I said to this man that if my father had been alive, he would almost certainly have been at Lord’s for the one-day game. When I mentioned his name, he said he had played a Taverners game with him once - given that my dad used to spend most of his time in the field making phone calls, texting or sunbathing - this must have been a trying experience.

When the news was confirmed later that day, I thought first of my father. I could hear him clearly in my mind celebrating the news, planning trips to Test matches and anticipating another trip to Lord’s (where he went every year). I was glad I’d talked to a cricket man about my father and cricket on this day.

My dad saw no reason why everyone couldn’t love cricket. He believed it was a gripping game and he saw it in romantic terms, a struggle between the forces of convention and conformity on one side, and those who could triumph with style by thinking big and bravely on the other.

My dad played Gaelic football for Austin Stacks and later for Kerry, but cricket was the game that sustained him all his life. An old childhood friend of his told me at his funeral how my father would organise summer games of cricket in St Brendan’s Park in Tralee. In his imagination, he was setting fields at the Oval, even if those he was playing with might not have shared his vision.

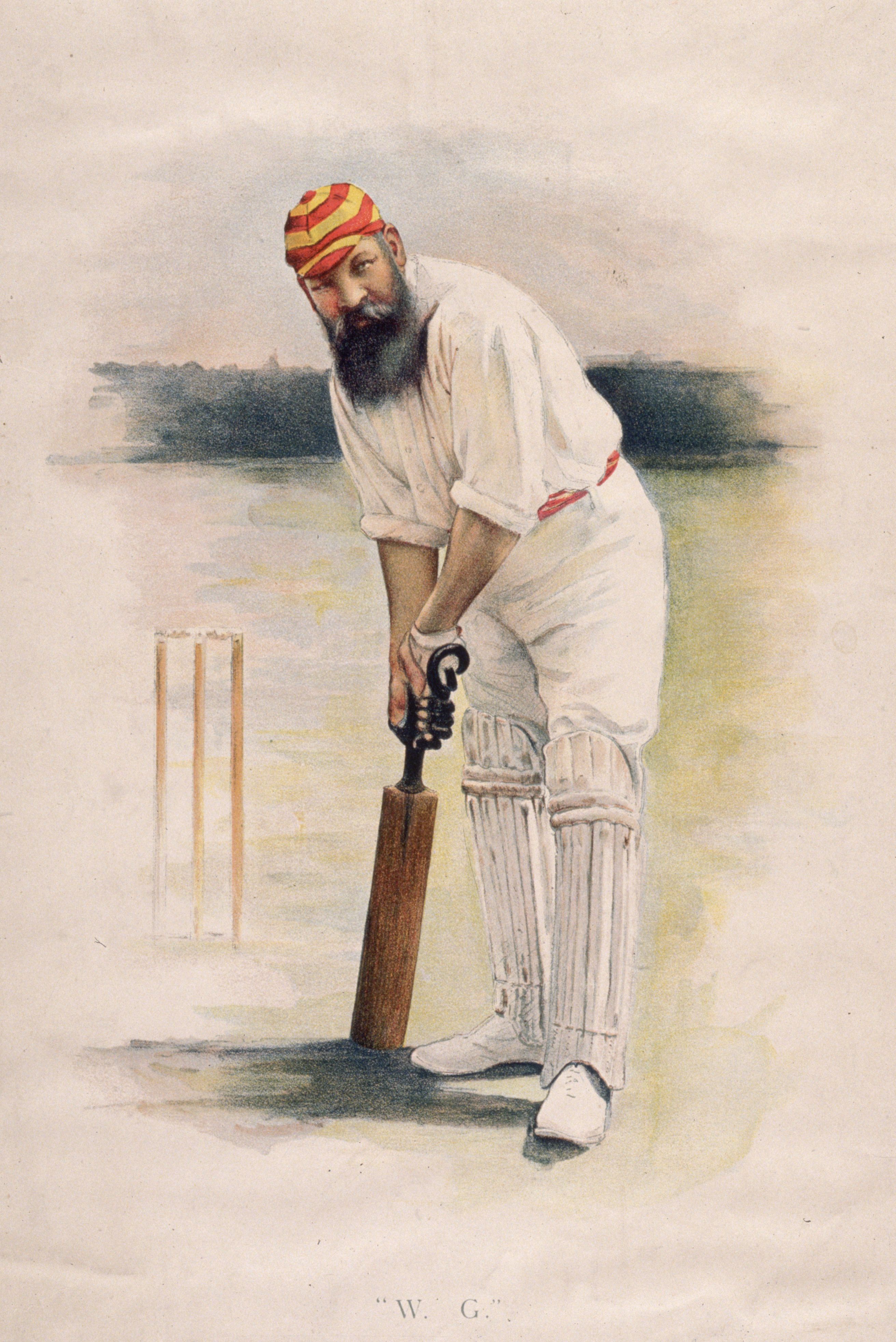

Tralee, of course, was not part of cricket’s heartland. My dad had been introduced to cricket by his brother-in-law who had developed an interest simply because he listened to the radio a lot and developed an obsession with the game through the BBC.My grandfather was a schoolteacher and, through their shared love of theatre, he was friendly with the district judge in Tralee RDF Johnson, who would give my father books on great cricketers like WG Grace and Ranji.

It was through these books, the radio commentary of John Arlott, the journalism of RC Roberston-Glasgow and the power of imagination that cricket became seared on the consciousness of a boy in the southwest of Ireland.

When I was young, I would play endless games of cricket with him during summer holidays in Brittas Bay. I would sometimes bowl off a long run like Bob Willis, disappearing into the ferns over a hill, before reappearing to sling in a ball that rarely gave any indication so much effort had gone into it, And then I would go through the whole process again.

He could just about put up with this, but everything he believed about the romantic pull of the game would be challenged when I insisted on batting in the manner of Chis Tavare, a name which to those who remember him explains an entire philosophy.

Tavare once took 332 minutes to score 35 against India in Chennai, then Madras. Alex Massie has described how he once considered Tavare the “anti-cricketer” who “appeared to bat under the impression that there was something mildly distasteful about scoring runs”.

So when I would take up summer days batting in the style of Tavare, it was a challenge to a man who had as low a boredom threshold as my dad.

But he would tolerate it. Because of love, I suppose. On the other hand, I adored it, whether I was poking the ball forward or hooking it into the river behind us. As a shy and solitary kid who really just wanted to spend time with him, I found this escape into endless games of cricket to be as good as summers could be. Over time, of course, these wasted days become part of family lore. I remember talking to him about the agony of watching Neil McKenzie take more than nine hours to score 138 at Lord’s in 2008 and he laughed and reminded me of those days in Brittas, as if all the hours of him putting up with Tavare had been leading to the time (the 553 minutes of time) when I would sit and watch much of this innings. He always knew ways to beat the boredom, especially at Lord's where he could go and get a steak sandwich or a pie, pop into the betting tent or have a nap on the grass at the Nursery end surrounded by the papers and Wisden. Ideally he would do all three.

It is, of course, an important part of structure of Test cricket that there are long passages when, if a spectator isn't quite bored, he is acutely aware that things aren't exactly exciting at this moment.

All this glorious mystery now awaits Ireland. In a couple of years, there will be, it is hoped, a Test match against England at Lord's. If and when the bell rings and the players walk out through the Long Room, it will be another emotional moment for those who have guided Irish cricket to this extraordinary position, It will be another gathering for the cricket community which grows all the time thanks to its welcoming and inclusive spirit. And it will be another day when some of us hear the voices of those who can't be there, those we wish could witness it most of all.

He always knew ways to beat the boredom, especially at Lord's where he could go and get a steak sandwich or a pie, pop into the betting tent or have a nap on the grass at the Nursery end surrounded by the papers and Wisden. Ideally he would do all three.

It is, of course, an important part of structure of Test cricket that there are long passages when, if a spectator isn't quite bored, he is acutely aware that things aren't exactly exciting at this moment.

All this glorious mystery now awaits Ireland. In a couple of years, there will be, it is hoped, a Test match against England at Lord's. If and when the bell rings and the players walk out through the Long Room, it will be another emotional moment for those who have guided Irish cricket to this extraordinary position, It will be another gathering for the cricket community which grows all the time thanks to its welcoming and inclusive spirit. And it will be another day when some of us hear the voices of those who can't be there, those we wish could witness it most of all.Explore more on these topics: