Share

4th June 2016

12:45pm BST

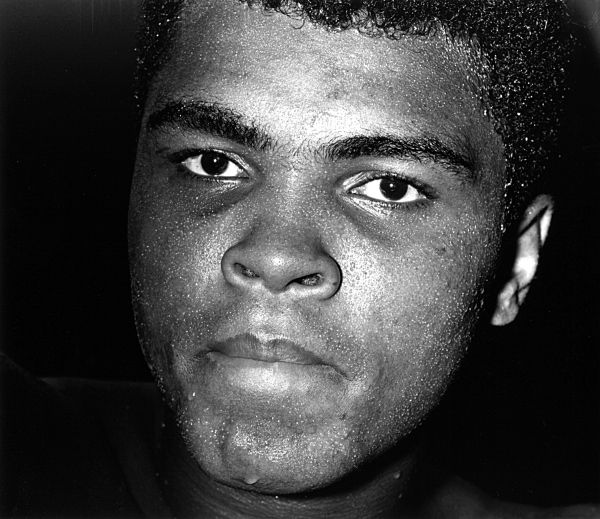

Muhammad Ali was right. He was the greatest. He was the greatest cultural force of the past 100 years, and yet, like other popular figures such as the Beatles and Elvis Presley, there is a case to be made that Muhammad Ali was underrated.

He was underrated because somehow we came to accept all he had achieved and forgot how extraordinary it was. On the weekend of his death, we remember again and it seems remarkable once more.

In an age of shared emotion, it has become easy to dismiss any expression of sadness on social media for a figure people didn’t know personally. Yet all of those who woke up on Saturday morning and felt a jolt when they heard the news of Muhammad Ali’s death or found a tear falling from their eye as they listened to that glorious voice and watched that beautiful face weren’t guilty of some conceit or manufactured grief.

They hadn’t imagined a connection with Muhammad Ali, his genius was that he created one. For Black America, he was a symbol of defiance and a force for change, but for millions of others he represented something too. He represented a freedom of spirit and a creativity that was untrammelled.

We had watched Ali live like few men have lived and we had watched him die like we all must die. We had marvelled, even in retrospect, at his achievements and willed him on during the long years of his illness.

https://twitter.com/SportsJOEdotie/status/739014850412568576Of course, we are mourning something that we have lost ourselves, even if it is just a nostalgic memory or, more profoundly, a shared experience of watching Ali with a father or a mother who are no longer around to share this experience. It also reminds us of something we spend our lives trying to ignore: that those we love who may have loved Ali all their lives are not invincible either.

Ali persuaded us of his invincibility, while rarely hiding his vulnerability, even if it was just the smile that played on his lips as he made his most outrageous remarks.

But he was underrated too because he maintained for the most part a grace and an integrity when assailed by the rampant force of mass popularity that would have caused others to bend and break, to become a caricature or a parody of themselves.

Ali, of course, had to endure mass unpopularity as well as mass popularity during the 1960s when he beat Sonny Liston to become world champion, almost immediately announced his conversion to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

In 1964, the year he became heavyweight champion of the world, he also took his military qualifying examination. Ali, who had struggled in school, failed the mental aptitude test and, after a retest to make sure he hadn’t faked it, was declared “not qualified under current standards for service in the armed forces”.

There was some outrage but Ali wasn’t drafted until two years later when, with the war in Vietnam getting worse, the mental aptitude qualification was lowered and Ali was reclassified.

In Thomas Hauser’s magnificent biography, the journalist Robert Lipsyte recalled being at Ali’s house in Florida when the local TV reporter came by to tell him he was now eligible to fight in Vietnam. Lipsyte said he saw a man who was frightened at all that he now may lose.

For the rest of the day, Ali answered the phone to reporters, until finally he exploded. “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

Now that statement reads like a gloriously defiant stance against a futile war. Then, much of America saw it as an unpatriotic act, and even worse a statement that demonstrated all that was wrong with modern America.

Jimmy Cannon talked about the “whole pampered style-making cult of the bored young”. Another writer said Muhammad Ali had “squealed like a cornered rat” when called up by the army. A year later, Ali arrived at an army station in Texas where new soldiers were inducted into the US Army. 26 men were there and 25 stepped forward when they were called. When they called out “Cassius Marcellus Clay”, Muhammad Ali didn’t move. Ali was informed he had committed a felony punishable by up to five years in prison.

Within an hour, the New York State Athletic Commission had suspended his boxing license and he was effectively stripped of his title. Soon he was convicted and his passport taken away. He was exiled from boxing and denied the opportunity of making a living in the ring.

During his exile, America’s perception of him changed, just as America was beginning to think differently about Vietnam.

He returned to the ring in 1970 and in 1971, he fought and lost to Joe Frazier. The ugly side of Ali’s personality had been apparent in the way he taunted Frazier before that fight. Ali turned Frazier into a figure only racist white America should support, which was a denial of the truth about Joe Frazier.

There were other possible fights too. He nearly fought the basketball star Wilt Chamberlain but the fight collapsed when Chamberlain arrived to confirm the bout. Ali had been urged by his lawyers to say nothing until the contracts were signed and he told them not to worry, he knew this was a lucrative fight. As Chamberlain walked into the office to sign the deal, Ali looked up at the seven foot two basketball player and roared, ‘Timber!”. The blood drained from Chamberlain’s face, he realised how crazy the idea was and the fight was off.

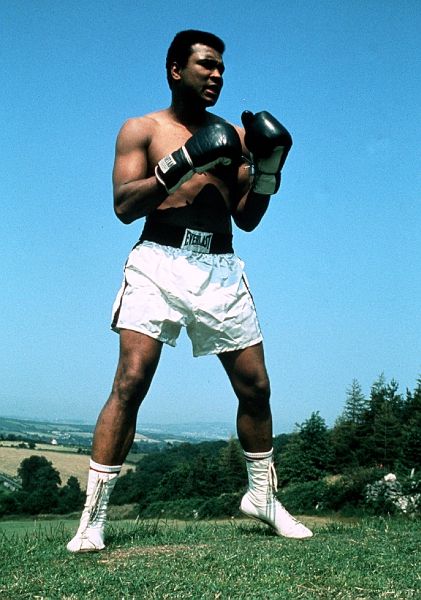

Ali fought Frazier three times after his return, the years when he became a figure of virtually unchecked popularity, even if they were the years - and the fights - which did the damage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J410tzVWoB4He wasn’t the fighter he had been before his exile and the new tactics like the rope-a-dope brought more punishment than any man could bear.

They also brought moments which will live forever, that remind us of how one man can change everything.

Before he fought George Foreman in Zaire, Ali gave a press conference in the Waldorf Astoria in New York. He was 32 years old and about to face a man regarded as one of the most fearsome boxers of all time. As Norman Mailer among others pointed out, Ali was fearful of what could happen when he stepped in that ring, but he would talk his way round that fear. In the Waldorf Astoria, he riffed magnificently as he sat alongside Don King, who would rise to prominence on the back of this fight (just in case anyone had forgotten about sport’s ugliness).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTkOYXKbcrUAli was mischievous and eloquent and poetic, but he was mainly beautiful. He was always beautiful. He wondered how many writers were calling it for George, and he glanced over at King in a way which suggested he knew where he had come from and where he was going. Then he considered Foreman.

“This chump has got everybody scared. Scared of what? Nothing to be scared of," his voice grew fainter, "...scared of what?"

He would beat Foreman, of course, in a manner which shook the planet. And in a world where there is so much to be scared of, Muhammad Ali made it seem as if fear, like everything else, could be conquered.

Explore more on these topics:

Boxing | SportsJOE

boxing